The Spring of Reckoning: How International Economic Organizations Are Changing Their Vision of the Future of the Global Economy

[Чтобы прочитать русскую версию статьи, выберите русский в языковом меню сайта.]

The global medium-term prospects are not all doom and gloom.

International Monetary Fund [IMF 2024, April. P. 78]

Leonid Grigoryev — academic supervisor and tenured professor at the School of World Economy and section head at the CCEIS, HSE University.

SPIN RSCI: 8683-3549

ORCID: 0000-0003-3891-7060

ResearcherID: K-5517-2014

Scopus AuthorID: 56471831500

For citation: Grigoryev, L., 2024. The Spring of Reckoning: How International Economic Organizations Are Changing Their Vision of the Future of the Global Economy. Contemporary World Economy, Vol. 2, No 1.

Keywords: economic development, business cycle, forecasts, growth drivers.

Abstract

In 2024, a series of reports from international and private research institutions offered a cautious and rational analysis of the global economic situation. The complicated economic growth of 2011-2019 was followed by the turmoil of 2020-2023. In the midst of geopolitical conflicts, the global economy has entered a phase of uneven recovery. The current situation should be considered as a shift in the socio-economic development regime. In these circumstances almost all major actors—from the head of the IMF to the Pope—see some certain risks and threats in world processes. Positive GDP dynamic has been restored, but at a level lower than at the beginning of the 21st century. China supports the momentum of global economic growth.

The current global landscape can be pictured as follows: emerging and low-income economies are lagging behind the developed economies in terms of economic growth, with no signs of convergence; the EU economy is essentially stagnant, with risks of further deterioration in the economic outlook; and only the US has hardly managed to return to its conventional economic growth rates. Sluggish global growth is accompanied by a significant divergence in the economic dynamics among the major players. With low revenue growth, the resources available to governments have shrunk, especially in the face of an increasingly complex set of challenges. While the cyclical recovery appears weak, its drivers over the next two to three years (investments in renewable energy, electric vehicles and artificial intelligence) may provide some additional impetus, albeit not very strong. Generally, the world has finally taken a look at its current position, but the conclusions and solutions remain unclear.

Introduction

The economic and geopolitical upheavals of recent years are forging a new pattern of global economic development: there are changes in macroeconomic dynamics by continent, country and sectoral economic structure, trade patterns, structural shifts in industry, infrastructure and energy. Global regulatory institutions, which are in decline since the 2008-2010 global financial crisis, have been shattered by geopolitical contradictions. The slowdown in economic growth has already triggered a competition for resources between poor countries and the impoverished classes in developed countries, with the latter apparently winning. The macroeconomic parameters of the recovery (economic growth, unemployment and inflation rates) could be considered well within acceptable historical norms for advanced economies, except for two circumstances. The first is the associated risks and uncertainties. The threat of collapses in various sectors of the economy and the emergence of crises are both creating a sense of insecurity among the major players, which is reflected in the current global media, causing politicians to remain depressed and anxious at the same time. The second factor is geopolitical contradictions: negotiation processes are taking place between parties with different and even divergent interests, which are in conflict on several levels. On top of this, there are elections and the expectation of elections for parliaments, presidents and other governmental bodies and levels. The segmentation of global financial markets, growing inequalities between countries and societies, crises and conflicts—this is a vivid manifestation of the fragmentation of the socio-economic “fabric” of the world and the reason why hopes for the attainability of the Sustainable Development Goals are fading.

This paper describes the main features of the global economy development at its current state. The first section includes analysis of the general framework of the economic development: the steady stationary regime of 2020-2023 and later that has been unfolding before our eyes. The second section discusses the cyclical component of modern economic development. The final section examines the drivers of economic growth and structural shifts beyond the current conjuncture. The paper considers what might influence the pace and nature of global socioeconomic development in the years ahead (2024-2026), assuming the absence of new major financial, energy or geopolitical shocks.

1. A forgotten familiar regime

The current period of 2023-2025 is the years of economic recovery, albeit moderate. After the end of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, a prolonged inflation, which was largely caused by the anti-crisis fiscal stimulus and large fiscal injections, has been slowed down in 2023. However, the nature of the recovery is somewhat reminiscent of the early 1980s: inflation is significantly higher than in the previous decade and economic growth is uneven amid high oil prices [Grigoryev and Ivashchenko 2011]. During that period economic growth declined in both the EU and Japan, while now it is declining in the EU and China. The parameters of the decline were much more dramatic then, but nowadays we observe similar economic dynamic and macro concerns.

2023-2024 we perceive as a period of relatively high interest rates “regime” relying on the fact of the stability of the Fed and ECB policies (key interest rates are around 5%), the forecasts of international organizations and the ongoing scientific debate. Inflation, the second parameter of such regime, has declined in the US and the EU due to the reduced contribution of the energy and food sectors, and core inflation (excluding energy and food prices) remains relatively low at 2-3%. Since 2020, however, cumulative inflation (three-year CPI) is high: 17.5% in the US and 19.7% in the EU (see Table 1). Nevertheless, the key challenge is not the current level of monthly inflation, but the intensity of the growth of unit labor costs or, in the politicians’ words, the inertial growth of nominal wages [Grigoryev et al. 2024]. With the instability of geopolitical factors, there is a high probability of the future fluctuations in commodity prices. The inertia of wage and service price growth in the developed world has the unpleasant peculiarity of the grassroot fire—with a gust of inflationary wind, inflation might soar again. The central banks’ cautious approach to the monetary policy is explained not as much by model calculations—there are simply not enough statistical data for that–but by the fear of missing the return of inflation.

Minimum wage systems, employment contracts, and corporate relationships are adapting to the realities of the current labor market environment. Economists typically view rational interests and decisions as the primary and determining factors of the actions of firms and financial authorities. But in the context of frequent elections, the outcome of which is unknown and now depends on the unstable preferences of fragmented electorate groups, the logic of politicians is changing. We may see “non-optimal” decisions not only on the world arena, with sanctions distorting the market logic of governments’ and companies’ decisions, but also caution on the part of central banks, finance authorities and governments regarding social policy decisions and regional issues solutions. The frequency of elections on various important issues in a stable regime is an important factor to consider regarding the electorate preferences. With crisis events, alarming forecasts, conflicts of party interests, and electoral media activity, the priorities of economic agents shift from basic profit maximization, efficiency improvement and risk-taking to caution. This does not stop economic growth and capital investments but reduces their intensity. It is complicated to calculate the damage caused by one or another aspect of macro policy during recovery period, when even the mistakes (explicit or implied) that led to crises in the past are difficult to assess in terms of GDP losses.

Table 1. GDP and CPI dynamics (%), 2019-2025

|

Annual growth rate of the CPI (%) |

|||||||

|

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 (f) |

2025 (f) |

|

US |

1.8 |

1.3 |

4.7 |

7.8 |

4.1 |

2.8 |

2.4 |

|

China |

2.9 |

2.5 |

0.9 |

1.9 |

0.7 |

1.7 |

2.2 |

|

EU-27 |

1.4 |

0.7 |

2.9 |

9.3 |

6.5 |

3.7 |

2.4 |

|

Developed economies |

1.4 |

0.7 |

3.1 |

7.3 |

4.6 |

3.0 |

2.2 |

|

Developing economies |

5.1 |

5.2 |

5.9 |

9.8 |

8.5 |

7.8 |

6.2 |

|

Annual growth rate - core CPI (%) |

|||||||

|

US |

2.2 |

1.7 |

3.6 |

6.2 |

4.9 |

- |

- |

|

China |

2.9 |

2.5 |

0.9 |

1.9 |

0.8 |

- |

- |

|

EU-27 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.8 |

4.7 |

5.7 |

- |

- |

|

Economic growth, % of real GDP |

|||||||

|

US |

2.3 |

-3.4 |

5.6 |

2.1 |

2.5 |

2.1 |

1.7 |

|

China |

6.1 |

2.3 |

8.1 |

3.0 |

5.2 |

4.6 |

4.1 |

|

EU-27 |

1.2 |

-7.2 |

5.2 |

3.3 |

0.5 |

0.9 |

1.7 |

|

Developed economies |

1.7 |

-4.9 |

5.0 |

2.6 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

1.8 |

|

Developing economies |

3.7 |

-2.4 |

6.5 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

Source: compiled by the author according to IMF, OECD, Eurostat, Trading Economics, National Bureau of China.

A year ago, we pointed out that the difficult transition to the recovery phase took place [Grigoryev 2023], despite the fact that the crisis of 2020 was not “cyclical” in terms of the depth and nature of the financial turmoil. We can now note with satisfaction that we managed to avoid a massive “trap” and a critical downturn of the world economy in 2023. The high interest rates of the Fed and the ECB are gradually pushing up 10-year bonds yields, which in return leads to higher cost of public debt financing and firms’ capital investment.

Global economic growth fluсtuations are largely mediated by international flows of migrants, goods and finance. Recent years—since the outbreak of COVID-19—have shown some peculiar shifts in these linking and constitutive areas of globalization. First, migration to developed countries has increased dramatically [Economist 2024]—after a shock in 2020, both the US and the EU have seen massive inflows of low-wage labor. In 2023, the number of people entered US exceed the number of people left by 3.3 million, in Canada this metric stood at 1.9 million people, in UK at 1.2 million people, and in Australia at 0.74 million people, meaning that the Anglo-Saxon countries alone gained about 7 million people. The EU is also breaking records in terms of the number of immigrants. Given the complex (due to aging) demographic situation in the developed world, the influx of labor at relatively low cost and to the lower social strata appears to be advantageous, even if the payoff is not immediate. We would reserve this point for closer examination in the coming years, particularly regarding the migration of educated workers. At least the US benefited in terms of economic activity and employment in the current period.

The large-scale inflow of migrants coming from different cultures, lifestyles, nationalities, and often religions leads to the development of social imbalances and potentially to political and electoral tensions (especially given the complicated naturalization rules). The rise of right-wing parties in Europe and the deepening split over migration issues in the US suggest that the demographic and labor market gains and the social and political problems of immigration may diverge over time, with problems becoming more acute over time. It is worth noting that this has become an ongoing factor and will have an increasing impact on government spending, political program platforms, and the configuration of government coalitions and policies for the foreseeable future. This is an example of how social issues that have always been significant, but in the new environment of geopolitical tensions and lower medium-term economic growth rates are turning into a source of increased social instability.

At the international level, the “Global South” and especially the expanded BRICS are becoming the new key development factor and the focus of analysts’ attention. The inertia of quasi-liberal global governance has been eroding since the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. The April IMF review cites data on the expansion of industrial policy measures (mainly export support) since 2009: 6,000 measures in developing countries against 5,000 in developed countries [IMF 2024. P. 103, Fig. 4.1.1], with a significant impact on developing economies. However, there is no clear assessment of the size and impact of export subsidies in developed countries. In fact, we observe the use of industrial policies beyond catch-up development. For a significant number of medium-developed countries (with GDP per capita of $15,000 PPP 2017 and above), the issues of completing physical infrastructure, developing human capital, and raising labor productivity remain very important (as they are, of course, for less developed countries). The example of China points out the need to maintain the efficient use of a high savings rate over time. Maintaining high economic growth rates by a group of countries with significant balance of payments surpluses and high levels of public and private remittances (e.g. from the Gulf countries to India and Egypt) could lead the BRICS countries to use their own financial resources more intensively in the future.

Changing the global financial architecture to ensure stable economic growth in developing countries remained nothing more than a buzzword at conferences for a long time. Now, economic growth and investments are slowing down at the same time, and competition for financial resources for energy transition and climate policy is intensifying. Poverty reduction, social and economic development, and, in particular, the catching-up development of middle-income countries require well-organized financial resources along the entire “value chain”: from the choice of spending priorities to reliable sources of financing, access to technology, and process organization. Decades have been spent on direct fight for poverty reduction, and now the focus is on the climate change.

Recent geopolitical environment has sparked a new round of action in climate change mitigation. The Atlantic Council and the Policy Center for the New South project of April this year has proposed 5 points [Canuto et al. 2024. P. 11] to increased climate and the SDGs finance. Presumably, this is a set of tools for a permanent interaction between the West and the South, something that the Bretton Woods institutions have conventionally been responsible for. This makes the outcome more interesting:

- Multilateral development banks (MDBs) should focus on financing national public goods aimed at climate change adaptation.

- A Green Bank should be established within the World Bank Group with the goal of climate change mitigation.

- Efforts to create a carbon market should be redoubled.

- MDBs balance sheet management should be optimized.

- There should be a general capital increase for the World Bank and other MDBs and a substantial replenishment of concessional lending resources to their units.

The proposed set of measures is straightforward and falls within the “classic” mix of development banks and private initiative. It also includes various ideas for debt relief for less developed countries, mainly linked to the climate policies. International finance institutions (IFIs) typically connect green finance to human capital and infrastructure development (creating energy-efficient infrastructure, human capital in innovative green industries, etc.). However, de facto there is a need for more integrated and coordinated approach to development—linking finance mainly to the climate agenda put off the human capital development, physical infrastructure and other SDG goals “for later”—after the energy transition [Bobylev & Grigoryev 2020; Grigoryev & Medzhidova 2020]. We question whether it is realistic to achieve climate goals in the short term (especially before 2030) without global development coordination. In these challenging times, we should expect a strengthening of the UN and the entire SDG movement. In the fall of 2023, a new report on the SDGs was released with the striking title: “Times of Crisis, Times of Change” [United Nations 2023]. Its publication went relatively unnoticed, and its influence was rather limited, as the report was lost among other UN decisions and documents.

The world community has lost a lot of time in 2020-2023. The recently proposed steps even regarding the creation of new institutions, as we have shown by the example of the Financial Report, are promising. Although, it is not certain that such meausure can become adequate solutions to the complex, interrelated and seemingly escalating challenges. Moreover, virtually all these problems involve complex negotiations, difficult agreements, large resource requirements, and inevitable difficulties in setting priorities across countries and sectors. The definition of a working institution is the norm and a way of enforcing its performance. So far, we have seen an increase in the intensity of developed country trade disputes with China, affecting a significant component of “climate mitigation goods” for which China has become a mass exporter, including renewable energy equipment and electric vehicles. But restrictions on Chinese exports in this segment could slow down emissions reduction. Geopolitical fragmentation and the current system of global institutions are incompatible partners, and time is running out to solve global problems.

In general, the expectations of the global community in the coming years can be gauged from the IMF’s regular reviews of the global economy. In January 2023, fears of recession were very strong, and the main focus was on the geoeconomic fragmentation of the world economy. In 2024, the tone of the assessment of the state of the economy has softened a little. However, in June 2023 IMF assessed fragmentation losses as very significant: “Trade disruptions poses losses to global living standards as severe as those from COVID-19” [Bolhuis et al. 2023. P. 35]. The worst-case scenario did not materialize, but the protracted difficulties also had a depressive effect.

Overall, the prospects for the return of globalization would be generally good, provided that stability in international affairs returns, tensions are reduced, and the intensity of sanctions is reduced. We note the IMF’s classification of the world development periods from 1870 to 2021, which highlights periods of increasing and decreasing trade openness. We would record another small period of the second half of the 1970s – early 1980s, which is flat in Figure 1 [IMF 2023. P. 6], following the 1973-1975 crisis. Perhaps the slowdown in globalization after the global financial crisis and at the moment are phenomena of a similar order. But this is not a reason for optimism in the current situation, since global problems and the need for resources have become more acute and the geopolitical situation in the world has not improved.

Figure 1. Trade openness (% of GDP), 1870-2021

Source: IMF, 2023. World Economic Outlook: Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. P. 6.

The IMF’s April 2024 review gives the impression of a “sigh of relief” as 2023 passed without a sharp economic downturn, although geopolitical risks remain, and economic growth is still slow. Among the highlighted risk factors and future growth slowdowns, we will point out a fundamental issue that is currently difficult to specify and remains uncertain for the future: growing geoeconomic fragmentation [IMF 2023].

The sustainability of global economic growth, albeit at a slower pace, depends on the US, the EU, China, and the Middle East (i.e. oil prices). This framework defines the global outlook for the next two years, which enlightened observers see quite similarly. The differences lie in their assessments of the impact of several elections, geopolitical factors and risks, the trajectory of the Chinese economy, and the energy transition. The expected low (relative to previous decades) average annual GDP growth rate of 3.1% over the next five years is not a technical feature of the system but a reflection of a significant decline in the growth of resources available to address domestic, structural and global challenges. As well as increased political competition for the resources available to governments.

The world is in a period of nervous but relentless growth. The debate about the future of the world, the paths of its development, and the solutions to the world’s problems is unfolding before our eyes. The broader issue of sustainable development has been somewhat overshadowed, although energy and climate remain at the center of political attention. At the same time, industrial policy has made a comeback (as discussed in this year’s IMF April Review). The debate in the academic mainstream, however, no longer looks like a cry against the all-conquering neoliberalism, as Nobel laureate J. Stiglitz points out: “Populist nationalism is on the rise, often shepherding to power authoritarian leaders. And yet the neoliberal orthodoxy—government downsizing, tax cuts, deregulation—that took hold some 40 years ago in the West was supposed to strengthen democracy, not weaken it. What went wrong? Part of the answer is economic: neoliberalism simply did not deliver what it promised” [Stiglitz 2024].

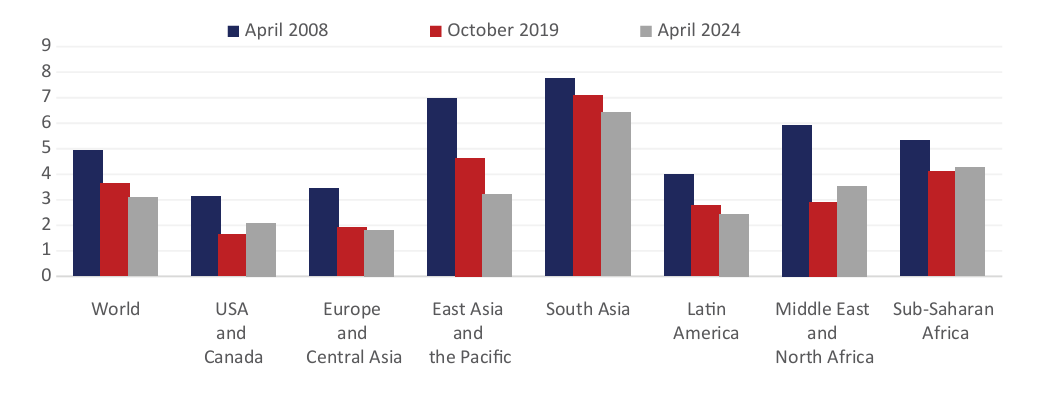

Figure 2. Five-year real GDP forecasts by region from IMF surveys, April 2008, October 2019, and April 2024 (%)

Source: International Monetary Fund, 2024. World Economic Outlook—Steady but Slow: Resilience amid Divergence. Washington, DC. P. 67.

Inequalities between countries and social strata and unresolved global problems dominate. Geoeconomic fragmentation has already cost the world several percentage points of GDP growth. Rising military spending and its likely further increases will also divert some of the funds and resources that could have been used to address global challenges. Expected regional economic growth rates in the coming years are significantly lower than at previous reference points (see Figure 2). The erosion of global development coordination raises questions about the ability of the world community to solve global problems and the future of development as a whole, which will be a key agenda in the coming years. It can be said that any increase in geopolitical tensions raises the temperature of the planet, both figuratively (politically) and literally.

2. Divergence in the growth phase

The world’s economic dynamics consist of the internal development of many countries and their interaction in the trade and financial sectors. In terms of growth drivers (and the composition of statistics), the world depends on the economies of US, China, and the European Union, which, firstly, produce, export, and finance more than others; secondly, they fight inflation and set interest rates; and thirdly, their demand dominates energy markets. The interdependence and competition of these three major economies define practical, rather than declared, problem-solving principles.

The expansion of the BRICS and the reorganization of world trade in the midst of geopolitical shocks have unleashed an outpouring of concern from international organizations and national governments about the Global South with an intensity not seen few years ago. The problem of reorganizing global finance as a tool for socio-economic development in the absence of country coordination seems difficult to implement and will take years. Thus, the entire global institutional system is undergoing a general “slow speed” reorganization within the framework of the existing complex relations between the key players. It would make sense to develop a trajectory for 2024-2026 for its reorganization and the directions of compromise seeking in order to return to the usual business cycle. But geopolitical fragmentation and a multitude of electoral events complicate decision-making and agreement among the leading players.

We believe, however, that we need to start looking at the global dynamics from the perspective of the world’s poorest countries, about which policymakers in the leading countries are formally concerned. The International Development Association (IDA), a division of the World Bank, covers the 75 least developed countries. They make up a very significant voting bloc at the UN, so in addition to being concerned about global development or the world’s poor, a number of countries have a very pragmatic interest in this story. After the liberation of the colonies, many new countries set out to develop: some succeeded, few went ahead, especially in Asia.

The debate about cross-country convergence has been going on for decades, and a large body of literature has been accumulated. Meanwhile, the success of developing countries in reaching the economic level of developed countries has generally fallen short of the expectations of the Bretton Woods Institutions [Easterly 2001] and academia, as well as developing countries themselves. But hope has been regularly renewed with theories and programs that have largely served the interests of donors [Morozkina 2019]. Perhaps it is time to abandon the concept of economic convergence of countries, at least with respect to most countries and the timing—many decades of catch-up development are needed [Grigoryev and Maykhrovitch 2023].

The events of the 2020s have led not only to economic growth slowdown in the world and its less developed parts, but also to the recognition of the changing tendency of developing countries to outpace economic growth compared to developed countries. The feasibility of achieving SDG 10 (Reducing Inequality) in terms of inequality across countries depends on this trend. The latest IMF survey [IMF 2024] recognizes the turn towards divergence in recent years, and the World Bank has published a report, “The Great Reversal,” which notes that countries (IDA) are lagging behind more developed countries. Note that the concentration of efforts in recent years has been focused on energy and climate policy, as we noted back in 2020 [Grigoryev, Medzhidova 2020]. So economic growth in the less developed part of the world has stalled, even with significant external support. And the world will once again have to grapple with the fundamental question of whether poor countries are morally, economically, and politically important.

The Chinese economy, regularly portrayed in the Western media as having intractable problems, continues to grow at a rate of 5-6%, a pace unrivaled by almost any other country except India. The country’s complex housing sector problems are the result of huge urban and social development programs. With a high degree of conditionality, they can be classified as a “middle development” problem, but not a “trap.” The formation of a “new normal” is, in fact, a path away from the achieved average level of per capita income of about USD20,000 in PPP terms. It should be noted that China’s methods of accelerated development over the past three decades have been hybrid in nature, using natural resources and natural advantages with the creation of entrepreneurial institutions and the use of an open world market [Grigoryev, Zharonkina 2024]. In the foreseeable future, China will face new challenges: increasing personal consumption with decreasing inequality, resolving the accumulated debt problems in the real estate sector, and supplying the world with electric vehicle cars and equipment for renewables production at a very competitive prices.

In terms of the global economic cycle, China will remain a growth leader with the prospect of reaching the income level of developed countries within a decade. China’s economic development goal was set by President Xi Jinping in 2019 to double its GDP per capita in 16 years, i.e. by 2035. China’s economic stability and growth are of paramount importance to the global economy. Country’s positive impact on global development has been significant and perhaps unfairly underestimated. Now IMF forecasts for the coming years de-facto are counting on China’s economic development impact, although at the same time OECD countries, especially US, are opposing China’s industrial policy in some export-related dimensions.

The US economy, as it happened before, is experiencing greater fluctuations than most of the world, but is nevertheless returning to its traditional growth dynamics. In a sense, it is a huge economic system that is evolving according to its internal logic of development. The recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic has been completed, and the savings surpluses of 2020-2021 have mostly shrunk. Core inflation growth still persists, so the Fed rates are still high. The US economy has been service-led in the post-pandemic era, so the unemployment rate is low (in an election year, by the way). Capital investment growth rates have reached roughly the rate of GDP over the past year, with an unusual concentration in the manufacturing sector, which may be a reaction to the legislation and envisioning of the domestic industries development in the future. The dramatic gesture of raising tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles imports echoes something similar in the past regarding Japanese car exports to the US. So an industrial policy that for so long has not been recommended to anyone is taking over.

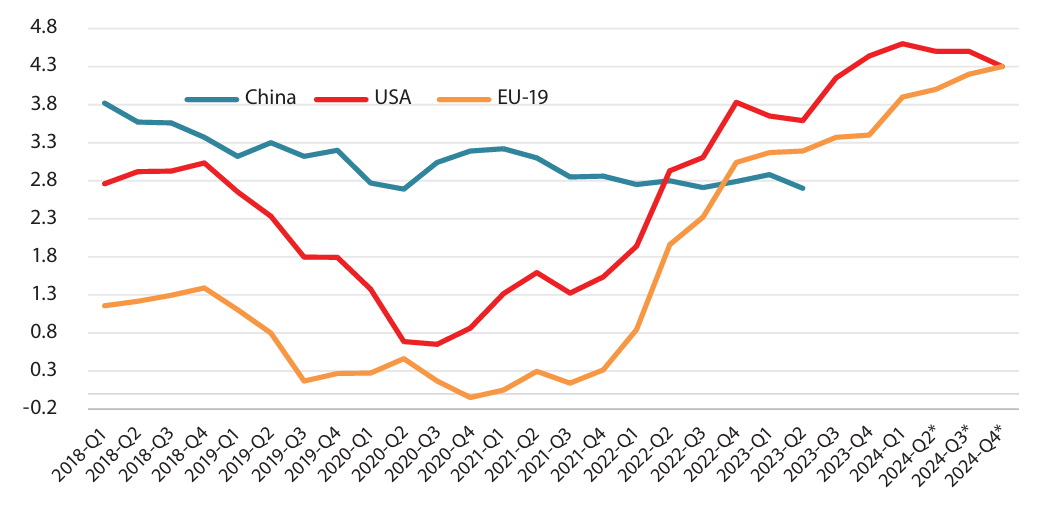

Three percent growth in US GDP, with intermittent crises, is the historical norm. The country has embarked on a growth trajectory out of very unusual circumstances. The massive debt problem has disappeared but has been put off to the “post-election” period, with the old “cheap” ten-year bonds being replaced by more expensive ones (short bonds have also appeared) (see Figure 3). Whatever the outcome of the 2024 elections, we can expect the problem of the rising cost of servicing the US federal debt to become a thorny issue in partisan relations again through the 2026 election and beyond. For now, we see a very cautious Fed policy: with core inflation still quite high by historical standards, Fed rate cut could cause inflation to move from a low base “smoldering” state to a high inflation state. So one of the unusual features of this recovery in the US is that it is occurring with high rate of prices growth, high interest rates and low unemployment—usually it has been the other way around.

Figure 3. Long-term interest rates on government bonds maturing in ten years (% p.a.), Q1 2018 - Q4 2024

Source: compiled by the author on the basis of OECD data.

The EU economy has become a byword: How could a prosperous continent be dragged into near stagnation for several years with only modest economic prospects for the future? It is clear that tourism-dependent France, Italy and Spain have been the main victims of the lockdowns, but tourism revenues are up again now, with not so great economic growth. Germany is conducting several costly experiments on itself at once in energy, trade restrictions and automotive industry. The Economist recently listed three shocks threatening Europe’s economy that we would like to comment on [Carr 2024]. The first is the energy crisis, which the author linked to the Ukrainian conflict. It should be noted that the EU created an energy system that failed under the conditions of natural shocks in 2021, leading to a price increase. Since then, the EU has incurred additional costs for energy imports, despite the consumption squeeze. In addition, there are new investment costs linkes to the need for rebuilding the energy system—especially with ambitious plans for climate programs, reinforced by the urgent ban of direct supplies from Russia. At the same time, rising energy prices are not a crisis itself—supplies have not been interrupted. Gas and oil (and coal) prices have stabilized and are now affecting competitiveness, especially in Germany.

The second shock is the wave of Chinese goods inflow into the EU, seen as an attempt by China to export “its slowdown.” In fact, European complaints about the export of Chinese renewable energy equipment and China’s consolidation in the global market are in sharp dissonance with the EU’s position on accelerated greenhouse gas emission reductions. Liberalism is clearly becoming inconvenient, but no radical means of accelerating exports from the EU are yet in sight, with Russia under sanctions, China a major exporter, and the US merely pulling production from the EU to itself. These “geo-trade” conspiracies are usually discussed as part of theories of development, trade or political relations. We would like to add that the EU has been facing a growth problem for five years now, and all its own solutions have failed to produce quick results. We point out that the EU’s difficulties in competing with the US and China have already become common topic and a recurring theme in the newspapers. The New York Times, for example, wrote on 5 June 2024 about the “competitiveness crisis” of the EU, which capital investments, income and productivity lag behind the two giant competitors [Cohen 2024].

Finally, the third looming shock is the possibility of Donald Trump being reelected as US president, which could lead to an increase in import tariffs from the EU. This raises legitimate concerns that unsuccessful tariff relugation by leading countries and alliances could prove to be a “remedy worse than the disease.” Overall, the EU, with its large social programs and climate ambitions, appears to be an economic organism designed for smaller commitments at higher rates of resource growth. Unless the EU gets on a trajectory closer to 3% of GDP growth, all the plans of Brussels and Berlin in the areas of energy, climate and social problems will face severe budgetary constraints and will be perceived more painfully by the electorate.

Against this backdrop, the ECB continues to keep interest rates high (see Figure 3), using much the same logic as the Fed: “Slowing down is bitter, but stimulating is scary.” To some extent, the European Union’s behavior seems to depend on the cource of affairs on external energy markets, China’s political decisions, and the “American roulette” of the presidential elections. It is likely that many European countries will wait until November to make further decisions on how to stimulate economic growth.

China plays a huge role in international trade, but the country is not immune to the business cycle and trade policies of leading partner countries. China’s trade flows in 2023 were largely driven by its relationship with the US and the EU (see Table 2, Figure 4). The decline in imports from China by the two trading giants, the US and the EU, has created some difficulties for the latter. De facto, the world has reached a situation of a “slowly growing shared pie” and fluctuations in importers’ demand have a conjunctural impact on exporters.

Table 2. Trade and flows in 2019-2023

|

Importer |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

|

Exports of Chinese products, billion USD |

|||||

|

US |

419 |

452 |

577 |

583 |

502 |

|

EU-27 |

367 |

391 |

519 |

562 |

502 |

|

The rest of the world |

1 712 |

1 745 |

2 266 |

2 448 |

2 385 |

|

Exports of US products, billion USD |

|||||

|

China |

106 |

124 |

151 |

154 |

148 |

|

EU-27 |

268 |

232 |

272 |

350 |

370 |

|

The rest of the world |

1 268 |

1 068 |

1 330 |

1 559 |

1 502 |

|

European exports, billion USD |

|||||

|

China |

253 |

259 |

310 |

285 |

282 |

|

US |

462 |

425 |

503 |

569 |

590 |

Source: compiled by the author based on Trade Map data

Figure 4. China’s export flows between leading countries in 2022

Source: compiled by the author based on Trade Map data.

The return of the world economy to trade openness and the acceleration of global growth through trade is only possible if restrictions on the flow of goods are eased and the intensity of industrial policies (in particular export subsidies) is curbed. For the time being, this remains an elusive dream, especially for the European Union. The global economic recovery is therefore unfolding with significant differences in growth rates and domestic drivers in the US, the EU, and China. The recovery parameters for 2024-2026 appear as “moderate recovery with moderate pessimism” to both market commentators and the IMF. According to our classification [Grigoryev 2023. P. 4], the current phase can be classified as type “F - broad back of upturn.” However, it is uneven across regions, characterized by high inflation, tighter monetary policy, and, as noted by the IMF, a dangerous development of geopolitical conflicts. We should also consider potential natural disasters (including those caused by rising temperatures) in some regions and armed conflicts (Sudan, Haiti) in others, which also increase risks and limit resources for further addressing socio-economic development issues.

3. Looking for structural drivers

Historically, major crises have led the global economy to a different type of growth through the asset obsolescence. The global financial crisis of 2008-2009 had led to a tighter banking control, a slowdown in the investments under low interest rates and low inflation [Grigoryev et al. 2022. Chapter 2]. Now we are witnessing industrial policies of developed countries in the form of subsidies, sanctions, merger bans, forced sales of companies, lawsuits, special R&D programs, which, without entering textbooks, have returned to actual business practice.

Instead of a cyclical boom in capital investments, there is a decline in trade openness, high interest rates, which generally does not contribute to a rapid recovery. Hope lies in the energy sector, especially renewable energy, electric vehicles, and artificial intelligence (AI), to the extent that their development can be discerned on the horizon of a conventional multi-year boom. In this paper, we do not look far into the future, as strategies are still being formulated and their success will largely be dependent on the sustainability of economic growth in the coming years.

The US business cycle model has autonomously generated volatility for the rest of the world for at least a century, although the model itself is significantly affected by the world through trade and capital flows. In the current period, the US economy has already experienced a brief but intense housing boom. Now, due to cheap energy and other factors, energy-intensive industry has been pulled from the European Union into the US. In other words, the drivers of post-crisis growth are working, even if interest rates and the inflation fight are not fueling the pace of that growth. Structural shifts will move towards the use of AI, but large-scale effects in this area will not occur quickly, given the fact that the labor force is constantly migrating into the country which enables labor price restraint. The use of AI in many areas, as it happened before with bygone innovations, can lead to improved product quality (diagnoses in medicine), increased consumer reach (as well as government influence), reliability of systems, and so on. These subtle effects do not necessarily lead to significant increases in consumption levels for the relatively poorer groups of society in both developed and developing countries.

A number of recent actions by President Biden (including imposing a 100% import tariff on Chinese electric vehicles) have been characterized by the press as industrial policy, which is debatable—but these debates relate more to the content, rather than the nature of the policy itself. Similarly, the US has complaints about China’s industrial policy. But the days of fighting against the principle of industrial policy, which was taking place in 1990-2008 and influenced Russia’s domestic reforms, are over. We now live in a world of shrinking trade openness, sanctions, and export subsidies. One must assume that the power of export subsidies of developed countries is now higher than that of developing countries. This goes against the whole logic and letter of open world trade in general and the WTO in particular. Combined with sanctions and growing protectionism, it completely changes the nature of world trade.

China’s industrial policy is being projected outward through exports of renewable energy equipment and electric vehicles. This is a “zero-sum game” that simultaneously involves conflicts of interest and cognitive dissonance. The zero-sum situation stems from the desire of EU and US countries to produce adequate renewable energy equipment themselves in order to achieve the goal of 100% decarbonization of the economy by 2050. We see a conflict of interest between their own producers (supported by green parties) and the suffering countries and regions of the world: the latter need to reduce emissions as soon as possible to keep global temperature rise within 1.5-2° C. The EU has been and remains the leader of the movement, but China produces a disproportionately large amount of the equipment needed for this industrial policy.

Accusations against China are growing before our eyes in parallel with the strengthening of industrial policy in the Western countries themselves. In a recent New York Times article, China was accused of spending 1.7% each of the years 2017-2019 to support manufacturing. Note that the accusation boils down to the fact that this is far more than other countries are spending, so the accusation is about scale, not principle: “The West’s adoption of industrial policy is a departure from the ideology of open markets and minimal government intervention that the US and its allies previously championed” [Cohen et al. 2024]. As a result, China is simply to blame for being ahead of other countries in implementing industrial policy, which does not require commentary. And the cognitive dissonance is that only China can provide the equipment at affordable prices to implement global climate policy now, not sometime in the future. So the West’s anti-China industrial policy is simultaneously trying to curb China’s high-tech breakthroughs in the upper levels of technological progress, its massive exports of technological goods, and its economic growth, while at the same time trying to carve out a place for Western goods through tariffs (even if that means wasting time on urgent climate policy).

The trillions of dollars that COP-28, held in Dubai in December 2023, expected the world to raise to mitigate climate change are still materializing quite slowly. Developing countries have not received the long-promised $100 billion per year until 2023. The choice between climate and income is now very clear. And it is about growth drivers in the years ahead, which the current trade wars are disrupting. Note that the total cost of achieving zero emissions by 2050 was estimated in the McKinsey 2022 report [McKinsey 2022] at $275 trillion, or 7.5% of global GDP over that period. This figure seems realistic in its scale and indicates that the world community has not yet really begun to tackle the climate issue.

The problem of the EU falling behind the US and the competitive threat from China is nothing new to academia and the media. We highlight negative trends in labor productivity in the EU [Arse, Sondermann 2024]. The scale and risks of this issue for the EU have become clear by 2024. Accordingly, the question of “what to do” arises. Perhaps the most detailed and colorful are the analyses and recommendations of McKinsey in their report of 16 January 2024 [Giordano et al. 2024]. The report shows that the EU is lagging far behind the US and needs urgent solutions to a whole range of issues with a horizon of 2030. The list is striking in its scope and radicalism:

- A sharp increase in corporate spending on innovation;

- 2-3-fold decrease in electricity and gas prices;

- Increased capital investment of 400 billion euros and 200 billion more in new renewable energy projects;

- A two-fold increase in the size of European firms;

- Retraining 18 million workers and industrial automation;

- Supply chain change with increased import independence;

- Government regulation and strong industrial policy.

The list itself is adequate enough to solve the problem of the 27% lag in per capita income from the US. The question is how the 27 EU countries can raise the funds and organize the whole package, because the EU is not China in terms of industrial policy coordination.

The issue of climate change mitigation has several related aspects. First, investments in renewable energy are designed to increase energy capacity to meet growing energy demand, especially in developing countries. This reduces potential emissions but not always actual emissions. For example, the growing share of renewables in Germany’s fuel and energy mix in recent years has replaced the phase-out of nuclear power, while the share of coal has remained almost unchanged. In developed countries, the introduction of renewable energy in many cases represents a substitution of traditional capacity—expenditure without increasing energy consumption for the goods or services production. This is inevitable at this stage of the energy transition, but it leaves open the question of the speed of substitution and the demand growth for primary energy. At this point, naive ideas of 2020 regarding the rapid disappearance of coal, oil and even natural gas from the energy mix by 2020 have already “cooled off.” Preserving the planet’s climate is realistic only with huge expenditures, a focus on developing countries, coordination of logistics, investments, production of appropriate equipment, and cooperation among major powers. Every step taken to increase geopolitical tensions is, in essence, literally heating up the planet.

The world energy forecast by Russian authors Kulagin et al. (2024) presents three global energy development scenarios, assuming no massive investment in climate programs. In all scenarios, significant oil and gas consumption remains, mainly as a result of growing demand from developing countries. The International Energy Forum report concludes: “Annual upstream investment will need to increase by $135 billion to a total of $738 billion by 2030 to ensure adequate supplies. This estimate for 2030 is 15% higher than we assessed a year ago and 41% higher than assessed two years ago due to rising costs and a stronger demand outlook. A cumulative $4.3 trillion will be needed between 2025 and 2030, even as demand growth slows toward a plateau” [IEF 2024. P. 4].

In practice, this means that investment in renewables, even on a very large scale, does not occur through a simple redirection of financial flows from oil and gas companies; a more complex and lengthy process is underway and will continue in the future. In terms of economic recovery, we see that the traditional energy industries continue to operate at a level that supports recovery but does not trigger a large-scale boom. They are competing with green energy for funding.

A combination of structural changes typically plays the role of recovery driver in traditional business cycles, along with cheap loans, energy and labor. In the current situation, this role is being played by energy-climate programs designed to replace traditional energy capacity and save energy while meeting the world’s growing consumer needs. The production of energy-efficient and environmentally friendly equipment is certainly a stimulating factor. But declining investments in conventional energy capacities and underinvestment in energy in developing countries make us think about the cumulative effects. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 seems unlikely. Cyclical factors alone look sluggish: energy is still not cheap. Interest rates will remain high to curb inflation, which the authorities are trying to bring down to 2010-2019 levels.

Social problems are likely to worsen in the coming years; in particular, coal miners will have to be employed as part of any radical program to reduce coal production while cutting consumption. There will be increased competition between the poor in the developed countries and the “outsiders”—the developing countries. Military spending will increase, once it gets into a spiral of escalation. And solutions and funding will continue to be sought for the costly challenges of the coming years:

- financing the poorest countries development;

- climate programs financing;

- financing social equalization in the EU and the US;

- financing aging physical infrastructure in developed countries;

- financing growing military expenditures;

- financing national and regional programs in developed countries related to regular elections.

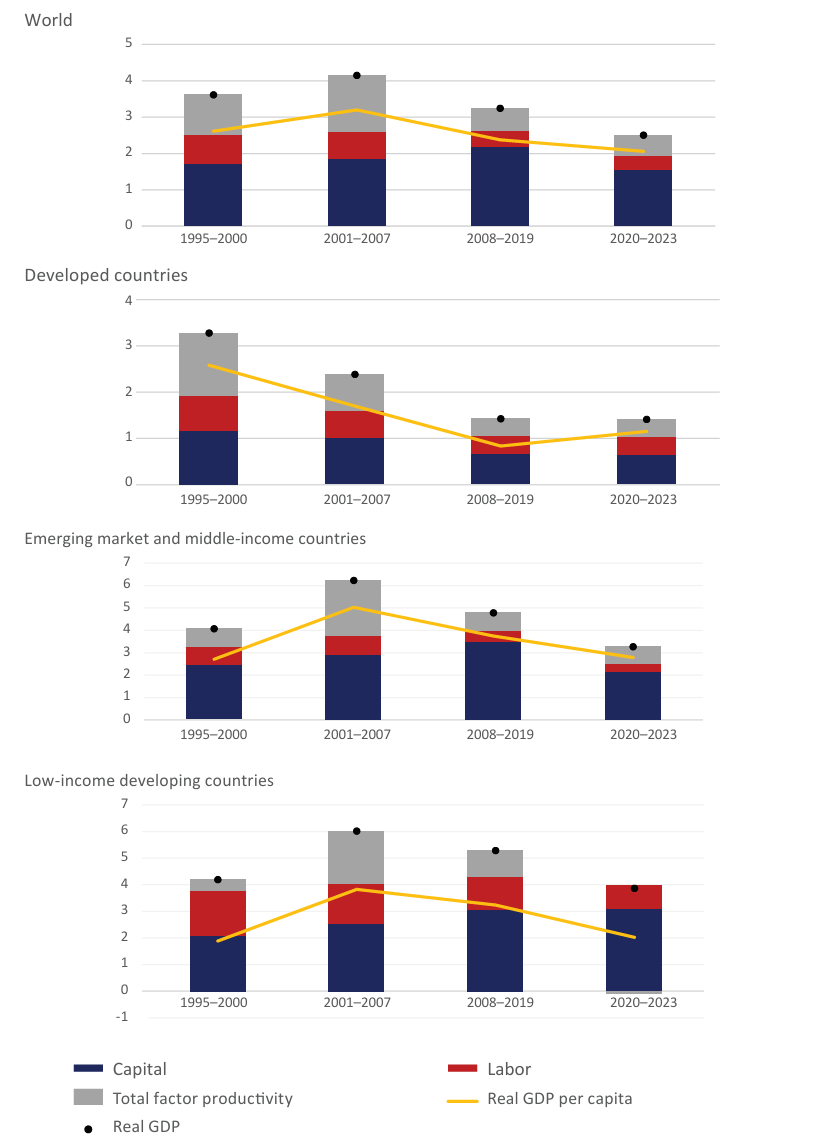

Figure 5. Contribution of components to GDP growth, 1995-2023 (%)

Note: Growth decomposition sample includes 140 countries

Source: IMF (2024). World Economic Outlook: Steady but Slow. Resilience amid Divergence. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. P. 68.

Figure 5 illustrates an important aspect of global developments over the past decade and a half—the declining role of real capital investments in advanced economies’ economic growth. Emerging and middle-income countries, especially China, have been the driver of global economic growth, largely due to return on capital investments. This pattern raises the question of the importance of this countries group in the future. Support for low-income countries will be required in terms of stimulating the growth of overall factor productivity, which has been stagnant over the past four years. The observed two percent growth in GDP per capita for this group of countries implies a very slow pull towards more developed countries.

Options that take into account the positive effects of AI have begun to appear in forecasts. In general, we are eagerly awaiting an increase in the quality of medical care, diagnostics, and individualized treatment, but only in developed countries. The process has just begun and it will certainly be costly, both in terms of invention and in terms of expansion of application. But for now, it is an early stage in the development of the industry and the spread of a new kind of service. On the horizon of 2024-2026, it does not look like AI could change the direction of economic dynamics in the medium term.

Conclusion: The glass is half full of optimism and half full of pessimism, or vice versa!

By the beginning of 2024, the formation of a complex and not particularly favorable regime of socio-economic development in the world had become recognized by most policy makers and analysts. The emergence from recession into an uneven nervous upswing leaves observers with an uneasy choice between cautious medium-term optimism or pessimism, depending on the country, profession, or political disposition. One can rely on IMF head K. Georgieva’s three possible paths for the world in the 2020s: “Making the right policy choices will define the future of the world economy. It will define how this decade is remembered—will it go down in history as

- the ‘Turbulent Twenties,’ a time of disturbance and divergence in economic fortunes;

- the ‘Tepid Twenties,’ a time of slow growth and popular discontent; or

- the ‘Transformational Twenties,’a time of rapid technological advancements for the good of humanity?”

Our work, as it seems to us, indicates that the global economy is in a state of “turbulence” and that global actors are aware of this and are scrambling to extricate themselves from it. So far, at best, it is moving into a “no-fun” state. K. Georgieva’s hope for a “transformational” path seems very distant, especially since she only refers to technological happiness. International financial institutions never make bad predictions—they only recommend good policy choices. But the issue today ’should not just be about the rapid technological advances that are gradually becoming available to the wealthy in both the developed and developing world. It is, clearly, about social and geopolitical stability and the coordination of the global community’s efforts, about removing geopolitical obstacles to solving global problems.

Bibliography

Arse, Ó., Sondermann, D., 2024. Low for long? Reasons for the recent decline in productivity. The ECB. May 6. Available at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/blog/date/2024/html/ecb.blog20240506~f9c0c49ff7.en.html

Bobylev, S., Grigoryev, L., 2020. In search of the contours of the post-COVID Sustainable Development Goals: The case of BRICS. BRICS Journal of Economics, No. 2, P. 4‒24.

Bolhuis, M.A., Chen, J., Kett, B., 2023. The costs of geoeconomic fragmentation: Disruption in trade threatens losses to global living standards as severe as those from COVID-19. International Monetary Fund. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2023/06/the-costs-of-geoeconomic-fragmentation-bolhuis-chen-kett

Canuto, O., Hafez, C. O., Ghanem, Y. E. J., Le Bouder, S., 2024. The Reform of the Global Financial Architecture: Toward a System that Delivers for the South. Atlantic Council, The Policy Center for the New South. P. 1‒35. Available at: https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/reform-global-financial-architecture-toward-system-delivers-south

Carr, E., 2024. Europe’s economy faces a triple shock. The Economist. Available at: https://www.economist.com/leaders/2024/03/27/the-triple-shock-facing-europes-economy

Cohen, P., Bradsher, K., Tankersley, J., 2024. How China Pulled So Far Ahead on Industrial Policy. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/27/business/economy/china-us-tariffs.html

Easterly, W., 2001. The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists’ Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics. Cambridge, MA; London, England: The MIT Press.

Giordano, M., Hieronimus, S., Smit, S., Chevasnerie, M.A., Mischke, J., Koulouridi, E., Dagorret, G., Brunetti, N., 2024. Accelerating Europe: competitiveness for a new era? McKinsey Global Institute. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/accelerating-europe-competitiveness-for-a-new-era

Grigoryev, L., 2023. The Shocks of 2020–2023 and the Business Cycle. Contemporary World Economy, Vol. 1, No 1. Available at: https://cwejournal.hse.ru/article/view/17238

Grigoryev, L., Ivashchenko, A., 2011. Global Investment-Saving Balance. Voprosy Ekonomiki. No 6. P. 4-19. Available at: https://doi.org/10.32609/0042-8736-2011-6-4-19 (in Russian).

Grigoryev, L., Zharonkina, D., 2024. China’s Economy: Thirty Years of Surpassing Development. International Organisations Research Journal. Vol. 19. No 1. doi:10.17323/1996-7845-2024-01-08

Grigoryev, L.M., Kurdin, А.А., Makarov, I.A. (eds), 2022. The World Economy in a Period of Big Shocks.Moscow: INFRA-M (in Russian).

Grigoryev, L.M., Maykhrovitch, M.Y., 2023. Growth theories: The realities of the last decades (Issues of sociocultural codes — to the expansion of the research program). Voprosy Ekonomiki. No 2. P. 18-42. Available at: https://doi.org/10.32609/0042-8736-2023-2-18-42 (in Russian).

Grigoryev, L.M., Medzhidova, D.D., 2020. Global Energy Trilemma. Russian Journal of Economics, No 6(4). P. 437‒462.

Grigoryev, L.M., Zharonkina, D.V., 2023. China’s Capital Formation in the Volatile Time. BRICS Journal of Economics, Vol. 4, No 2. P. 4‒24.

Grigoryev, L.M., Zharonkina, D.V., Maykhrovich, M.-Y., Kheifets, E.A., 2024. Mechanism of regime changes of global inflation in 2012–2023. Moscow University Economics Bulletin. No 1. P. 72-95 (in Russian). Available at: https://doi.org/10.55959/MSU0130-0105-6-59-1-4

IEF, 2024. Upstream Oil and Gas Investment Outlook. International Energy Forum & S&P Global Commodity Insights. Available at: https://www.ief.org/focus/ief-reports/upstream-oil-and-gas-investment-outlook-2024

IMF, 2023. World Economic Outlook: Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Available at: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/006/2023/001/article-A001-en.xml

IMF, 2024. World Economic Outlook: Steady but Slow. Resilience amid Divergence. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2024/04/16/world-economic-outlook-april-2024

Krishnan, M. et al., 2022. The net-zero transition. McKinsey & Company. January 2022.

Morozkina, A.K., 2019. Official Development Aid: Trends of the Last Decade. World Economy and International Relations. Vol. 63. No 9. P. 86‒92.

Stiglitz, J., 2024. Global Elections in the Shadow of Neoliberalism. Project Syndicate. May 1. Available at: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/2024-elections-grappling-with-authoritarian-populism-and-other-legacies-of-neoliberalism-by-joseph-e-stiglitz-2024-04

The Economist, 2024. Immigration is surging, with big economic consequences. April 30. Available at: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2024/04/30/immigration-is-surging-with-big-economic-consequences

United Nations, 2023. Global Sustainable Development Report 2023: Times of crisis, times of change: Science for accelerating transformations to sustainable development report. New York: United Nations. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2023-09/FINAL%20GSDR%202023-Digital%20-110923_1.pdf

World Bank, 2024. The Great Reversal: Prospects, Risks, and Policies in International Development Association (IDA) Countries. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/publication/prospects-risks-and-policies-in-IDA-countries

1.jpg)