Transformation of the European Union's Foreign Economic Policy in the Context of Open Strategic Autonomy

[Чтобы прочитать русскую версию статьи, выберите русский в языковом меню сайта.]

Egor Sergeev – associate professor, World Economy Department, and leading research fellow, Institute of International Studies, MGIMO University.

ORCID: 0000-0001-9964-9595

Author ID: 914172

Scopus Author ID: 57194348886

Researcher ID: AAN-2639-2019

For citation: Sergeev, E., 2024. Transformation of the European Union’s Foreign Economic Policy in the Context of Open Strategic Autonomy. Contemporary World Economy, Vol. 2, No 2.

Keywords: European Union, open strategic autonomy, foreign economic policy, trade policy, trade power, sanctions.

Abstract

Changing parameters of economic globalization along with the transforming nature of the world economic hierarchy leads to the fact that key players in the world economy have to reconsider not only their place and role in the changing system, but also traditional approaches to economic policy and its main instruments. The European Union is no exception in this system, which today sets rather ambitious tasks to maintain its position in the global economy, as well as to transform its geoeconomic power into geopolitical one. At least, this is how one might interpret the tasks set in the framework of the concept of open strategic autonomy of the European Union, which actually unambiguously unites different components of the Union’s security (military, political, economic, etc.). This allows us to consider the EU trade and investment (foreign economic) policy (together with a number of other areas of activity) through the prism of the realist paradigm in the framework of international relations theory and to try to identify new political economy features of the EU’s approach to its activities in the field of regulation of international trade and capital flows. By adjusting and transforming some key elements of external economic policy (primarily revising the parameters of preferential trade regimes, as well as approaches to bilateral and multilateral investment agreements), along with creating new coordination mechanisms and barriers to trade and capital flows (such as the Foreign Direct Investment Screening Mechanism and the Anti-Coercion Instrument), the European Union is strengthening the “protective” component of its integration model, trying to adapt the EU’s integration model to the changing parameters of the global economy. The mutual intertwining of the main directions of the EU’s activities is clearly visible, which also applies to relatively new aspects of the union’s positioning in the external arena (geoeconomic anticrisis policy, financial and monetary policies), which can potentially lead to new contradictions and limitations in the course pursued, taking into account the specifics of the integration structure.

Introduction

The contemporary global economy is undergoing a significant restructuring of established norms and patterns of interstate relations, accompanied by a profound transformation of the global economic hierarchy. If we apply the terminology of political sciences to the global economic system, we can talk about a kind of chaotization of processes [Lebedeva 2019], which should lead to the creation of a novel economic configuration of the world. In general, this formulation of the question reflects the tendency to reinforce the connection between global political and economic actors, which marks the return of global political economy as an explanatory paradigm of global development. The increasing complexity of international interaction, expanding conflict, growing economic interdependence, deepening digitalization, and rapid technological development contribute to the rising vulnerability of national economies, including to external influences, which many national governments perceive as significant threats. This, in turn, prompts key players to implement specific trade and other restrictions in the name of national economic security, with considerations of economic efficiency often becoming secondary, indicating a general securitization of the policy of global economic interaction [Hrynkiv 2022]. The most striking illustration of this phenomenon was the trade conflicts between the United States and China, as well as the evident “decoupling” in trade relations between the European Union and Russia.1

In this context, it is of academic interest to study the tactics and strategies of the leading centers of power in adapting to the changing environment and their vision of their future place and role within the transforming economic order. One particularly intriguing subject for investigation is the European Union. For an extended period, the EU has pursued a strategy of combining the advantages of free trade with a degree of protection in areas where its capabilities are constrained. This approach may be characterized as a form of “managed globalization” [Drynochkin, Sergeev 2023]. This paper proposes to examine the changes in the EU’s external economic (self-) positioning through the prism of the concept of open strategic autonomy (OSA), leaving the discussion of the EU’s membership out of the discussion. This approach will facilitate the identification of the EU’s potential actions in pivotal global markets, where competition is likely to intensify, and the constraints imposed by the distinctive features of the EU’s integration structure on the realization of its strategy.

Conceptualizing the changing role of the EU in the global economy

The most significant context within which the transformation of the European Union’s policy on its participation in globalization processes is taking place is the gradual but still steadily decreasing weight in the world economy and the reduction of competitiveness in a number of key industrial positions and technologies. A number of authors have even posited that the European Union is undergoing a geopolitical economic decline [Diesen 2023]. This situation aligns with the broader trend of rebalancing global forces and the decline of developed countries’ influence, which has prompted discussions on revisiting the stance of leading countries on globalization [Sjöholm 2024. P. 49–72]. Indeed, it is from this logic that the noteworthy report of M. Draghi for the new composition of the European Commission 2024–2029,2 which proposes more proactive measures to preserve and enhance the competitiveness of the EU, emerges.

It seems reasonable to posit that a similar political economy premise may also prove instrumental in facilitating the EU’s gradual transition toward a more robust and resilient global engagement, characterized by enhanced protection against contemporary manifestations of globalization. Furthermore, it may also inform the necessary adjustments to certain foreign economic instruments.

In light of the mounting tensions and crises, many of which have been of an emergency and exogenous nature for the European Union, the research community of the countries belonging to the association has expressed a desire for a “geoeconomic awakening” of the EU [Ribeiro 2023]. It is imperative for the EU to pursue this course of action in light of the disruption of global value chains, its critical dependence on numerous key goods and suppliers, geopolitical instability, and a desire to maintain its position in the international community. The aspiration to transform the EU’s preeminent role in the global economy into its geopolitical influence is regarded as a pivotal aspect of this “awakening” [Fabry 2022]. Furthermore, the objectives of addressing external economic imbalances, protecting against economic coercion, establishing a link between foreign economic strategy and EU values and sustainable development, and protecting critical assets and chains have been identified [Gehrke 2022]. In essence, the majority of researchers view all contemporary EU actions as an expression of this “geoeconomic awakening” [Olsen 2022], which can be considered a unifying paradigm.

It seems reasonable to posit that the EU policy itself is, in a certain sense, a reflection of these discussions in the research environment. This is because the decision-making system in the EU is largely technocratic and relies heavily on the expert environment to formulate its policy [Gornitzka, Sverdup 2010]. It is therefore unsurprising that the current trajectory of the EU is viewed as largely inevitable.

It seems that the logic of the transformation of the EU foreign economic policy should be considered in a kind of “realist” way (for details see: [Sergeev, Soroka 2024]), as well as in the spirit of the concepts of structural power and power transit, traditional for political economy, taking place in the modern world, which is quite consistent with the specifics of the moment in modern European studies [Postnikov 2020]. It is evident that the EU institutions are pursuing a policy that aims to exert influence on global affairs, leveraging the Union’s status as a major trading entity [Meunier, Nicolaidïs 2011] as well as a prominent regulator [Lavenex, Serrano, Büthe 2021]. Indeed, as a leading actor in global trade in goods and services, as well as capital flows, the EU is likely to employ these instruments to exert influence over its counterparts. It is similarly reasonable to anticipate the utilization of the right of access to the Union’s internal market by third countries as a competitive instrument. It is also noteworthy that there is a desire to extend the EU’s own standards, norms, practices, and “understandings” to its partners.

In light of the waning of traditional competitive advantages and economic development factors within the EU, this approach appears logical and, in many respects, non-alternative. This is particularly evident in the context of the slowing of economic globalization, which has resulted in a reduction in the intensity of major economic flows, the cessation of inexpensive energy, and the exhaustion of low- and medium-tech industries, which have largely shaped the face of EU industry [Guerrieri, Padoan 2024]. If we view the evolving globalization as an external shock to the EU, an exogenous crisis that will inevitably transform the Union’s behavior, then we can expect the EU to respond in a similar manner to previous crises. This response will entail the utilization of the EU’s strengths in the fight against crises and the creation of anticrisis “superstructures” in areas where its capabilities are limited. It appears that the EU’s efforts to articulate and operationalize the notion of open strategic autonomy should be interpreted within this framework.

At the heart of the EU’s current economic planning and programming is the concept of open strategic autonomy, within which the EU responds to the changing world order [Miró 2022]. As defined by the European Commission, it means “the EU’s ability to make its own choices and shape the world through leadership and engagement that reflects its strategic interests and values.”3 Indeed, the very debate on strategic autonomy is inextricably linked to the evolution of the EU’s (and member states’) attitude toward the question of EU “sovereignty” [Dupré 2022]. The emergence and development of the concept is extremely curious, as the idea of autonomy originally emerged in the sphere of the Union’s defense and security, only later (against the background of the Coronacrisis and the subsequent disruption of supply chains) moving to economic issues (the term “open” in this case means that the EU should maximize the use of its extremely extensive network of trade agreements to solve strategic problems, including reducing dependence on critical suppliers). In essence, we are talking about the extension of security principles not only to traditional defense issues but also to the economy—the securitization of the Union’s economic policy is taking place.

It should be noted that the scope of the OSA is quite broad: from trade policy (with the inclusion of an investment component) to finance. In the area of trade, the EU’s objectives include reforming the WTO; supporting the green transition and the development of sustainable value chains; supporting the digital transition and trade in services; strengthening the EU’s regulatory influence; deepening the EU’s global partnerships with countries in the neighborhood, in the future enlargement and in Africa; and focusing on the conclusion of trade agreements.4 In the area of finance, objectives include enhancing the global role of the Euro; building a strong, competitive, and resilient EU financial sector that supports the real sector and avoids reliance on third country financial instruments and infrastructure; ensuring the protection and resilience of financial market infrastructure; developing an effective sanctions management mechanism; and cooperating with partners.5

The revival of the EU industrial policy discourse is also an important element of the OSA concept [Drynochkin, Sergeev 2023]. It should be noted that for a long time, researchers have set themselves the task of linking the EU’s external economic policy with the overall competitiveness of the European Union [Gustyn 2017]. To a large extent, the OSA acts as such a link, as it aims to achieve greater resilience of the Union through the implementation of a more active industrial policy.6

Perhaps the need to maintain the EU’s competitiveness as a prerequisite for the implementation of the concept is even more important than the traditional reasons that appear in official EU documents. The most common reasons are the disruption of energy supplies from Russia and China’s restrictive measures against Lithuania. However, the goals of open strategic autonomy are set in 2021 (i.e., before the next wave of the EU energy crisis actively develops). Thus, it seems that the desire to preserve its competitive advantages and, in some cases, to protect itself from competition from third countries, underlies the adjustment of the EU’s main external economic instruments.

Is it possible to perceive open strategic autonomy as a conceptual phenomenon capable of structuring and transforming the EU integration construct in a new way (by analogy with the way some authors propose to consider the “green course” [Kaveshnikov 2024]), but in foreign economic policy? The answer to this question will be multidimensional. First, OSA cannot lead to the fulfillment of all the set goals due to its extreme ambition [Sidorova, Sidorov 2023]. Second, if one accepts that the key problem for the EU is its “critical dependencies,” the concept of OSA should have very limited manifestations in implementation issues, since according to various estimates “critical dependencies” account for less than 10% of EU trade [Mejean, Rousseaux 2024]. Third, the limitations and peculiarities of the EU’s integration construct do not allow for the implementation of all the aforementioned issues at the supranational level. Of all areas, only trade policy (and the movement of foreign direct investment; FDI) falls within the exclusive competence of the EU. Neither portfolio and other investments nor financial issues (with the exception of monetary policy in the euro area) can be regulated exclusively at the EU level.

Nevertheless, the OSA is a rather ambitious and far-reaching economic strategy. Most probably, it can and should be perceived as the European Union’s construction of its foreign policy and, to a large extent, its external economic identity (with all the limitations of the applicability of this term to the EU). By adopting a large number of strategic documents in this area, the EU seems to draw a certain picture of its foreign economic strategy and how it wants to be perceived internally and by third countries.

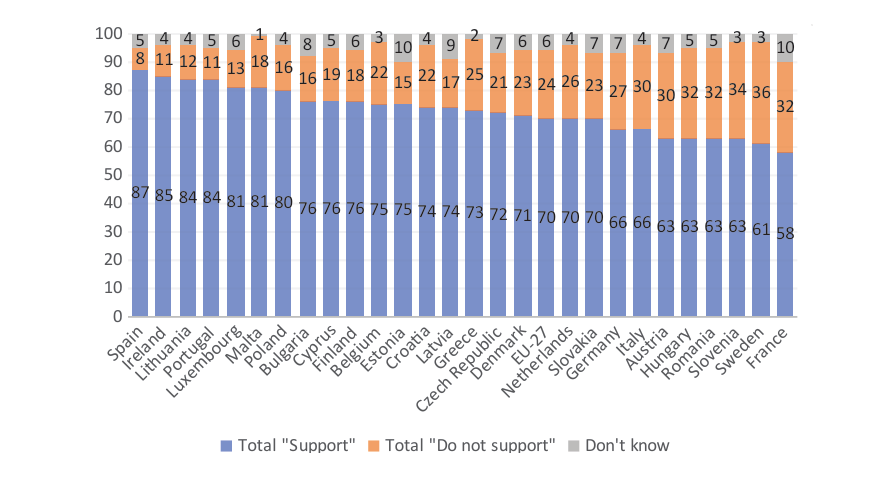

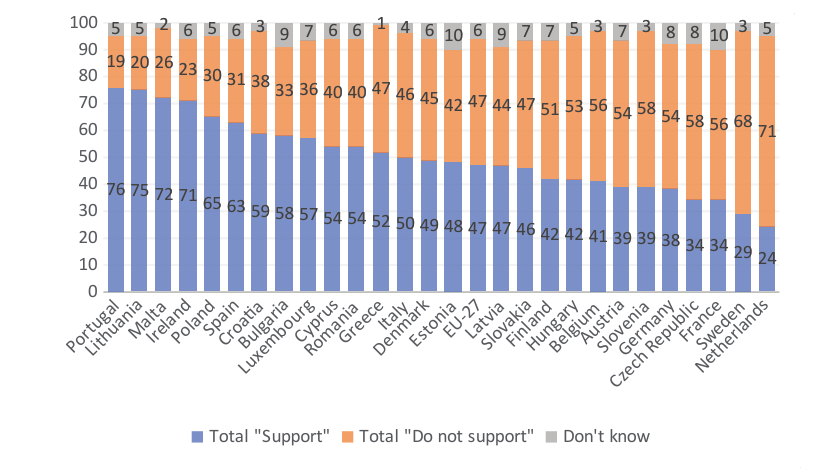

Indirect confirmation of this thesis is a kind of securitization of Special Eurobarometer surveys. In contrast to the 2019 trade policy survey, the most recent 2024 survey added a section on economic security. In addition, there is an increase in “protectionist” sentiment: according to 61% of respondents, the EU should apply higher import tariffs [Special Eurobarometer 2024. P. 81] (vs. 56% in 2019 [Special Eurobarometer 2019. P. 72]). The addition of a section on investment is interesting, reflecting the trend toward a growing link between trade and investment policies in the EU. In this section, one can also notice a rather obvious securitization component, expressed in the way respondents answer the questions on attracting foreign investment and on the purchase of national companies by foreigners differently (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Response to the question “Businesses often invest in other countries. To what extent do you support or oppose the following: Foreign business from outside the EU investing in (OUR COUNTRY) (%)?”

Source: Special Eurobarometer 554. Europeans’ Attitudes on Trade and EU Trade Policy. P. 60.

Figure 2. Response to the question “Businesses often invest in other countries. To what extent do you support or oppose the following: Foreign business from outside the EU buying businesses in (OUR COUNTRY) (%)?”

Source: Special Eurobarometer 554. Europeans’ Attitudes on Trade and EU Trade Policy. P. 61.

In general, the above set of issues and areas of the OSA fits into the logic outlined in the new EU Economic Security Strategy, which combines (quite in the spirit of the EU) three pillars:

- Promoting EU competitiveness and growth, strengthening the single market, supporting a strong and sustainable economy, and strengthening the EU’s scientific, technical and industrial base.

- Protecting EU economic security through a range of policies and instruments, including specific new instruments where necessary.

- Partnering and further strengthening cooperation with countries around the world that share EU concerns and with whom the EU has common economic security interests.7

Vectors of transformation of the main elements of the EU foreign economic policy

The emergence of the EU’s new articulated economic autonomy objectives is associated with a shift in the EU’s primary strategic orientations. Firstly, there is a certain degree of overlap between the EU’s principal areas of activity in the implementation of the concept of open strategic autonomy. Provisions pertaining to distinct domains of activity have a pervasive impact on adjacent domains. The issues of sanctions, trade in goods and services, the movement of investments, the conclusion of trade and investment agreements, economic, financial, and even hard security are inextricably linked and mutually intertwined. Secondly, the implementation of sanctions by the “geopolitical commission” has led to a significant expansion in the institutional role of the European Commission, while the involvement of member states in the initiation and adoption of sanctions has diminished considerably [Portela 2023]. Thirdly, a transformation is occurring within the Commission itself, with the objective of aligning its activities more explicitly with the goals of open strategic autonomy [Couvreuer 2024]. In summary, this illustrates the process of the EU’s re-emergence as a supranational institution in the context of crises.

In conclusion, the implementation of the provisions of OSA is already resulting in a notable transformation of the Union’s foreign economic instruments (for a detailed illustration of these changes, please refer to Table 1). The primary objective of this transformation is to integrate the established tenets of the EU’s foreign economic policy with the concerns of economic security. Furthermore, the aspiration to bolster the EU’s overall competitiveness adds another dimension of the new anticrisis “superstructure” of foreign economic policy instruments, which can be seen as a novel approach to aligning the goals of foreign economic policy with the industrial competitiveness of the EU [Guerrieri, Padoan 2024].

It is also noteworthy that, in light of the imperative to maintain the EU’s global standing, areas of EU activity that are not directly related to foreign economic activity are subject to some degree of revision (or, more accurately, adaptation). This is generally consistent with the challenges facing the Union, as a systemic change requires a systemic response. Consequently, in addition to the external aspects of economic transformation, the internal elements of the economic system are also being revised [Miró 2022]. Consequently, numerous conventional elements of integration (chiefly within the financial sector) that had previously impeded economic coordination are now being linked to the challenges of OSA. The necessity for further reform is also made evident by the Union’s overall competitiveness. This can be described as a form of securitization. Therefore, it is evident that there is a necessity for a reinforcement of the supranational element within the EU’s financial sector, which has become increasingly evident in the aftermath of the financial and debt crises. This objective should be pursued within the context of open strategic autonomy.

Table 1. Broad interpretation of new elements in the EU foreign economic policy

|

Policy direction |

Task |

Novel elements |

|

New trading and quasi-trading instruments |

Protection from “non-market” (according to the EU) competition of third country companies |

Foreign Subsidy Regulations.8 Use of increased import duties as a tool to combat non-market competition (example: increased duties on electric cars from China)9 |

|

Reducing the risks of exposure to countries that account for a significant share of exports/imports |

Anti-Coercion Mechanism (potential measures include import duties, restrictions on trade in services, intellectual property, restrictions on market access for FDI and government procurement).10 State aid rules for states affected by the actions of third countries (Lithuania and PRC trade restrictions)11 |

|

|

Termination (minimization of risks) from loss of industrial competitiveness in a number of key positions |

Export controls (especially on dual-use goods; example: restriction of exports of microchip manufacturing equipment from the Netherlands in 2023), commercial transaction controls, European Commission instructions to reduce foreign interference in R&D12 |

|

|

Global dissemination of EU internal market standards |

New EU standardization strategy13 |

|

|

Creating and maintaining global rules of the game on climate issues, maintaining the EU’s competitiveness in the energy transition environment |

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism as a trade instrument |

|

|

Trade agreements |

Diversification of geographic trade structure to address critical dependence on key supplier, access to critical elements |

Expansion of the network of preferential trade agreements, new initiatives to engage partners (e.g., Global Gateway strategy) |

|

Protection against competition from third countries in foreign markets |

Incorporating MFN provisions into trade agreements [Bohnenberger, Weinhardt 2022] |

|

|

Global dissemination of EU standards and “understandings” |

Attempt to introduce “essential conditions” (old—rule of law and human rights, new—“green transition” norms) into the EU’s general system of trade preferences,14 exclusion from preferential treatment for non-compliance with conditions (no agreement has been reached so far).15 Proposal to introduce a sanctions mechanism in case of “serious violations of key sustainable development provisions in trade, especially fundamental labor rights endorsed by the International Labor Organization, as well as the provisions of the Paris Climate Agreement”;16 introduction of “climate conditionality” prior to trade agreements |

|

|

Investment instruments |

Harmonization and deepening of integration in the domestic market |

Attempts to move from bilateral investment agreements concluded at the member state level to agreements concluded on behalf of the EU and to resolve contradictions between them [Sergeev, Soroka 2024] |

|

Protection against competition from third countries and protection against foreign interference in key assets |

FDI Screening mechanism17 |

|

|

|

Dissemination of EU norms and standards |

Green Investment Agreements (compliance with Green Deal norms in exchange for investment): first agreement with Angola in 2024.18 |

|

Reforming the global trade regime |

Restoration of WTO capacity |

EU proposals for WTO reform:19 through resolving the controversy surrounding the Appellate Body to meaningful reform; intensifying cooperation with individual partners within the WTO; creating a Multilateral Interim Agreement on Appeals and Arbitration |

|

New anticrisis (non-trade) instruments in the field of economic security (Geoeconomic anticrisis policy) |

Protection of the domestic market from sudden commodity crises |

Instrument for the protection of the single internal market in emergency situations (monitoring of the situation on commodity markets, warehousing and procurement of necessary goods on behalf of the EU in times of crisis) |

|

|

Impact on an agent who violates the economic “rule-based order” (sanctions as an external economic instrument) |

Export restrictions, control over commercial transactions (e.g., price ceiling mechanism for Russian crude oil and petroleum products) |

|

Currency policy |

The challenge to increase the global role of the euro |

Decision to deepen EMU integration20 (no practical steps so far); proposal to introduce a digital euro to strengthen its international role |

|

Financial policy |

“A strong, competitive and resilient EU financial sector that supports the real sector, avoiding reliance on third country financial instruments and infrastructure” |

Calls to finalize banking union, capital markets union; use of common EU debt instruments (including to improve their sovereign rating) to finance OSA activities |

|

Raise funds to realize the objectives of the OSA |

Use of the “NextGenerationEU” fund to finance “autonomization” in member states (to complete the energy and digital transition) |

|

|

“Development of an effective sanctions management mechanism” (protection against the extraterritoriality of other countries’ (US) sanctions combined with the impact on countries violating the EU sanctions regime) |

Reactualization of the EU Blocking Statute [Lonardo, Szep 2023], but attempts to interpret “EU territories” expansively to address sanctions circumvention;21 the idea of using access to the EU internal market as leverage against third countries [Bismuth, 2023] |

Source: compiled by the author based on McCaffrey C., Poitiers N.F., 2024. Instruments of Economic Security. Bruegel Working Paper 12/2024. Available at: https://www.bruegel.org/system/files/2024-05/WP%2012%202024_0.pdf; Baba et al., 2023. Geoeconomic Fragmentation: What’s at Stake for the EU. IMF Working Paper No. 2023/245. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2023/11/29/Geoeconomic-Fragmentation-Whats-at-Stake-for-the-EU-541864; The EU’s Open Strategic Autonomy from a central banking perspective. ECB, 2023. Available at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op311~5065ff588c.en.pdf ; Council Conclusions on the EU’s economic and financial strategic autonomy: one year after the Commission’s Communication, 2022. Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/04/05/council-adopts-conclusions-on-strategic-autonomy-of-the-european-economic-and-financial-sector/; own elaborations.

In the context of trade policy, the primary new remedial instruments are measures designed to address what the EU perceives as unfair market competition (for further details, see Table 1). Additionally, there are efforts to influence the association through the exploitation of its vulnerabilities by third countries. In this context, the Foreign Subsidies Regulation becomes relevant. Its implementation has already resulted in the imposition of higher tariffs on electric cars imported from China. Moreover, the mechanisms of protection against economic coercion have become a significant element of the policy landscape. These instruments are based on areas where the EU’s role remains highly influential, such as trade in services and the movement of foreign direct investment (FDI), or in sectors where the EU’s market is particularly attractive, such as public procurement. It would be remiss to ignore the use of export restrictions by the EU, which has employed this strategy with increasing frequency in its trade policy.

Of particular significance are non-tariff trade measures, which are employed with the objective of disseminating EU norms and standards, particularly in the context of climate policy. Additionally, the utilization of a Carbon Border Adjustment tax as a novel trade instrument has been observed [Baba et al. 2023]. In the context of EU trade agreements, the primary objective is to enhance the EU’s access to foreign markets while minimizing the adverse effects of competition from third countries.

It is notable that there has been a distinct increase in the link between trade and investment issues in EU activities, which is primarily expressed in attempts to resolve problems around bilateral investment treaties. Furthermore, there has been an apparent extension of securitization principles to FDI attraction policies. This is evidenced by the introduction of a foreign direct investment (FDI) monitoring mechanism, which involves joint FDI screening mechanisms but allows the final decision to be made at the country level. The degree of harmonization and effectiveness of this instrument remains relatively low, a fact that has not gone unnoticed by the European Commission, which has proposed further harmonization.22 In general, the implementation of the superstructure (albeit in an extremely fragmented and point form) in the EU investment policy is consistent with the trend toward a more selective approach of key players (primarily the US and the EU) to FDI inflows [Zuev, Ostrovskaya, Gilmanova 2022]. Similarly, the same can be said of all trade and quasi-trade measures. The EU policy, as evidenced by the issue of sanctions, is aimed at creating institutionalized mechanisms that allow for selective influence over counterparties, enabling the adjustment of parameters within its relations with them [Lonardo, Szep 2023]. In practice, the external economic provisions of the OSA concept extend beyond the domain of trade and investment. If we consider the EU’s position in the global economy as that of an integral player, the set of provisions stated in its conceptual documents gradually brings the EU’s actions (or intentions) closer to the foreign economic policy of national states. This includes, in addition to trade, elements of monetary, fiscal, and exchange rate policies [Oleinov 2016]. An evaluation of these developments (see Table 1) reveals a decline in the EU’s activity and effectiveness as it addresses matters beyond its exclusive competence, such as fiscal policy, and where the European Central Bank plays a more prominent role than the Commission in matters related to monetary and exchange rate policies. Nevertheless, there is a discernible inclination toward the hybridization of the EU’s areas of activity. For instance, sanctions issues are increasingly intertwined with the dynamics of financial markets. The imperative to enhance the Union’s competitiveness is becoming contingent upon financial mechanisms, such as the “NextGenerationEU” fund, or the oversight of such mechanisms, as exemplified by state aid rules. Moreover, the objective of strengthening the global role of the euro is being integrated with the pursuit of deeper financial integration. In consequence, the scope of matters assumed by the supranational level of governance (and, most notably, by the European Commission) is progressively widening.

Conclusion

In comparison to global practices, the measures taken by the European Union appear to be less innovative. Rather, it is the particular approach of the association to the trends that are currently prevalent in the global economy that is noteworthy. In the context of global trade, the primary challenges pertain to the difficulty of reforming the global trade regime and the proliferation of “neoprotectionism 2.0” instruments [Milovidov & Asker-Zade 2020]. Similarly, in the realm of capital flows, the strengthening of national restrictions and the introduction of novel protective mechanisms [Bulatov 2023] represent significant developments. In general, these trends reflect a growing emphasis on geopolitical considerations in the global economy. It seems probable that the EU, like many other key players, will tend to employ restrictive instruments and practices that are “convenient” and “habitual” for itself. In contrast to China, which is more inclined to act through informal channels, the EU is more likely to utilize formats that have already been disseminated domestically (e.g., state subsidy regulations for companies, the application of which is now de facto internationalized) or in which its role in the global economy is relatively significant.

The emergence of a “geoeconomic crisis” has prompted the European Union to initiate a process of transformation with regard to the instruments through which it engages in global economic processes. This transformation cannot be described as comprehensive or profound, as its primary objective is to facilitate the establishment of institutional mechanisms enabling the EU as an association and its member states as individual entities to participate in globalization on a selective basis and engage with their counterparts on a selective basis as well. This strategy may be regarded as reactive and even conservative in nature, reflecting a response to the structural changes occurring in the global context. Conversely, the ongoing transformation is genuinely systemic, with cosmetic changes permeating nearly all aspects of the Union’s foreign economic engagement. In general, the concept of open strategic autonomy, as it evolves and gradually expands in scope, provides convincing evidence to support this thesis.

Bibliography

Baba, C. et al., 2023. Geoeconomic Fragmentation: What’s at Stake for the EU. IMF Working Paper. No. 2023/245. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2023/11/29/Geoeconomic-Fragmentation-Whats-at-Stake-for-the-EU-541864

Bismuth, R., 2023. The New Frontiers of European Sanctions and the Grey Areas of International Law. RED, 5 (1). Pp. 8–13. Available at: https://geopolitique.eu/en/articles/the-new-frontiers-of-european-sanctions-and-the-grey-areas-of-international-law/

Bohnenberger, F., Weinhardt, C., 2022. Most-Favored Nation Clauses: A Double-Edged Sword in a Geo-Economic Era. In: A Geo-Economic Turn in Trade Policy? / Adriaensen, J., Postnikov, E. (eds). The European Union in International Affairs. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. Pp. 127–148. Available at: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-81281-2_6

Bulatov, A.S., 2023. New trends in capital flows in the world and Russia. Voprosy Ekonomiki. No 9. Pp. 65–83. Available at: https://doi.org/10.32609/0042-8736-2023-9-65-83

Covreur, S., 2024. Inside the European Union’s Trade Machinery: Institutional Changes in an Age of Geoeconomics. Journal of Common Market Studies [online first]. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jcms.13625

Diesen, G., 2023. Geoeconomic Power EUrope: The Rise and Decline of the European Union. Contemporary World Economy, Vol. 1, No 1. Available at: https://doi.org/10.17323/2949-5776-2023-1-1-33-51

Drynochkin, A.V., Sergeev, E.A., 2023. European Union: new trends of participation in the processes of globalization. In: New Trends in Economic Globalization / Bulatov, A.S., Galischeva, N.V., Maksakova M.A. (eds.). Moscow: Aspect Press, 2023. Pp. 165–192 (in Russian).

Dupré, B., 2022. European sovereignty, strategic autonomy, Europe as a power: what reality for the European Union and for what future? Robert Shuman Foundation. Schuman Papers, No 620. Available at: https://www.robert-schuman.eu/en/european-issues/620-european-sovereignty-strategic-autonomy-europe-as-a-power-what-reality-for-the-european-union-and-for-what-future

ECB, 2023. The EU’s Open Strategic Autonomy from a central banking perspective. Available at: https://www. ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecb.op311~5065ff588c.en.pdf

Fabry, E., 2022. Building the strategic autonomy of Europe while global decoupling trends accelerate. CES Discussion Paper. No 9. Available at: https://institutdelors.eu/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2022/12/221212-DP-ELVIRE-FABRY-CES-Final.pdf

Gehrke, T., 2022. EU Open Strategic Autonomy and the Trappings of Geoeconomics. European Foreign Affairs Review, Vol. 27, Special Issue. Pp. 61–78. Available at: https://www.egmontinstitute.be/app/uploads/2022/06/EU-Open-Strategic-Autonomy_Gehrke_2022.pdf?type=pdf

Gornitzka, Å., Sverdrup, U., 2010. Access of Experts: Information and EU Decision-making. West European Politics, No 34(1). Pp. 48–70. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01402382.2011.523544

Guerrieri, P., Padoan, P.C., 2024. European competitiveness and strategic autonomy. The European Union and the double challenge: strengthening competitiveness and enhancing economic security. LEAP Working Paper, No 5. Available at: https://leap.luiss.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/WP5.24-European-competitiveness-and-strategic-autonomy-.pdf

Gustyn, J., 2017. The Common Commercial Policy and the Competitiveness of EU Industry. In: The New Industrial Policy of the European Union / Ambroziak, A. (ed.). Springer. Pp. 145–170. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308960382_The_Common_Commercial_Policy_and_the_Competitiveness_of_EU_Industry

Hrynkiv, O., 2022. Export Controls and Securitization of Economic Policy: Comparative Analysis of the Practice of the United States, the European Union, China, and Russia. Journal of World Trade, No 56(4). Pp. 633–656. Available at: https://kluwerlawonline.com/journalarticle/Journal+of+World+Trade/56.4/TRAD2022026

Kaveshnikov, N. Yu., 2024. “Green Deal” as a Trigger of Deepening Integration in the European Union. World Economy and International Relations, Vol. 68, No 6. Pp. 93–107. Available at: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=67353321 (in Russian).

Lavenex, S., Serrano, O., Büthe, T., 2021. Power transitions and the rise of the regulatory state: Global market governance in flux. Regulation and Governance, No 15(3). Pp. 445–471. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/rego.12400

Lebedeva, M.M., 2019. Modern megatrends of world politics. World Economy and International Relations, Vol. 63, No 9. Pp. 29–37. Available at: https://www.imemo.ru/index.php?page_id=1248&file=https://www.imemo.ru/files/File/magazines/meimo/09_2019/05-Lebedeva.pdf (in Russian).

Lonardo, L., Szép, V., 2023. The Use of Sanctions to Achieve EU Strategic Autonomy: Restrictive Measures, the Blocking Statute and the Anti-Coercion Instrument. European Foreign Affairs Review, No 28(4). Pp. 363–378. Available at: https://pure.rug.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/826150988/EERR2023027.pdf

McCaffrey, C., Poitiers, N.F., 2024. Instruments of Economic Security. Bruegel Working Paper. 2024. No 12. Available at: https://www.bruegel.org/system/files/2024-05/WP%2012%202024_0.pdf

Mejean, I., Rousseaux, P., 2024. Identifying European Trade Dependencies. In: Europe’s Economic Security / Pisani-Ferry, J., Weder di Mauro, B., Zettelmeyer, J. (eds.). CEPR. Pp. 49–100. Available at: https://cepr.org/system/files/publication-files/200566-paris_report_2_europe_s_economic_security.pdf

Meunier, S., Nicolaïdis, K., 2011. The European Union as a Trade Power. In: International Relations and the European Union / Hill, C. and M. Smith (eds.). Second Edition. The New European Union Series. New York, USA: Oxford University Press. Pp. 275–298.

Milovidov, V.D., Asker-Zade, N.V., 2020. Protectionism 2.0: New Reality in the Age of Globalisation. World Economy and International Relations, Vol. 64, No 8. Pp. 37-45. Available at: https://www.imemo.ru/publications/periodical/meimo/archive/2020/8-t-64/economy-economic-theory/protectionism-20-new-reality-in-the-age-of-globalisation (in Russian).

Miró, J., 2022. Responding to the global disorder: the EU’s quest for open strategic autonomy. Global Society, No 37(3). Pp. 315–335. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13600826.2022.2110042

Oleinov, A.G., 2016. States’ Foreign Economic Policy: Theory and Methodology of Analysis World and National Economy. Available at: https://mirec.mgimo.ru/upload/ckeditor/files/mirec-2016-4-oleinov.pdf (in Russian).

Olsen, K.B., 2022. Diplomatic Realization of the EU’s “Geoeconomic Pivot”: Sanctions, Trade, and Development Policy Reform. Politics and Governance, No 10(1). Pp. 5–15. Available at: https://d-nb.info/1277071268/34

Portela, C., 2023. Sanctions and the Geopolitical Commission: The War over Ukraine and the Transformation of EU Governance. European Papers, No 8(3). Pp. 1125–1130. Available at: https://www.europeanpapers.eu/en/europeanforum/sanctions-geopolitical-commission-war-ukraine-transformation-eu-governance

Postnikov, E., 2022. Normative power meets realism: EU trade policy scholarship at the turn of the decade. Journal of European Integration, No 42(6). Pp. 889–895. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07036337.2020.1809774

Ribeiro, G.C., 2023. Geoeconomic Awakening: The European Union’s Trade and Investment Policy Shift towards Open Strategic Autonomy. EU Diplomacy Paper No 03. College of Europe. Available at: https://www.coleurope.eu/sites/default/files/research-paper/EDP%203%202023_%20Castro%20Ribeiro.pdf

Sergeev, E.A., Soroka, K.V., 2024. EU as a Trade Power: Adjusting Instruments of Foreign Economic Policy. Contemporary Europe, No 4. Pp. 71–83 (in Russian).

Sidorova, E.A., Sidorov, A.A., 2023. EU Strategic Autonomy in the Economy. Mezhdunarodnye protsessy, No 3. Pp. 119–142. Available at: https://www.intertrends.ru/jour/article/view/369?locale=ru_RU (in Russian).

Sjöholm, F., 2024. The Return of Borders in the World Economy: An EU-Perspective. In: The Borders of the European Union in a Conflictual World / Bakardjieva Engelbrekt, A. et al. (eds.). Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. Pp. 49–72. Available at: https://www.ifn.se/media/yk2nurmp/2024-sjöholm-the-return-of-borders-in-the-world-economy-an-eu-perspective.pdf

Zuev, V.N., Ostrovskaya, E.Y., Gilmanova, D.R., 2022. The Dilemma of Inward FDI in the EU and U.S. Investment Policy: Ensuring Capital Inflows and/or Strengthening Control of Strategic Assets? Outlines of global transformations: politics, economics, law. Vol. 15, No 6. Pp. 88–109. Available at: https://www.ogt-journal.com/jour/article/view/1300 (in Russian).

Notes

1 See: Altman, S., Bastian, C., 2024. DHL Global Interconnectedness Report 2024. Available at: https://www.dhl.com/global-en/delivered/globalization/global-connectedness-report.html

2 European Commission, 2024. The future of European competitiveness. Part A. A competitiveness strategy for Europe. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/97e481fd-2dc3-412d-be4c-f152a8232961_en?filename=The%20future%20of%20European%20competitiveness%20_%20A%20competitiveness%20strategy%20for%20Europe.pdf

3 European Commission, 2021. An Open, Sustainable and Assertive Trade Policy. Brussels, Feb. 18. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:5bf4e9d0-71d2-11eb-9ac9-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF

4 European Commission, 2021. Questions and Answers: An open, sustainable and assertive trade policy. Feb. 18. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_21_645

5 Council of the European Union, 2022. Note on Council Conclusions on the EU’s economic and financial strategic autonomy: One year after the Commission’s Communication. Available at: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-6301-2022-INIT/en/pdf

6 OECD, 2024. Procompetitive Industrial Policy – Note by the European Union. June 12. Available at: https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WD(2024)18/en/pdf

7 European Commission, 2024. Commission proposes new initiatives to strengthen economic security. Jan. 24. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_24_363

8 European Commission, 2023. Foreign Subsidies Regulation. Available at: https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/foreign-subsidies-regulation_en

9 European Commission, 2024. Commission imposes provisional countervailing duties on imports of battery electric vehicles from China while discussions with China continue. Jul. 4. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_3630

10 European Commission, 2023.New tool to enable EU to withstand economic coercion enters into force. Dec. 27. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_6804

11 European Commission, 2022. State aid: Commission approves €130 million Lithuanian scheme to support companies affected by discriminatory trade restrictions. April 26. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_2665

12 European Commission, 2022. Commission publishes a toolkit to help mitigate foreign interference in research and innovation. Jan. 18. Available at: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/news/all-research-and-innovation-news/commission-publishes-toolkit-help-mitigate-foreign-interference-research-and-innovation-2022-01-18_en

13 European Commission, 2022. Standardization strategy. Available at: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/single-market/european-standards/standardisation-policy/standardisation-strategy_en

14 The GSP Hub, 2023. A new GSP Framework. Available at: https://gsphub.eu/about-gsp/gsp-review

15 The GPS Hub, 2024. Ensuring Continuity: EU Extends Generalized Scheme of Preferences (GSP) Regulation until the end of 2027. Available at: https://gsphub.eu/news/GSP-extension-2027

16 European Commission, 2022. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. The power of trade partnerships: together for green and just economic growth, COM (2022) 409 final, 2022. Available at: https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/8a31feb6-d901-421f-a607-ebbdd7d59ca0/library/8c5821b3-2b18-43a1-b791-2df56b673900/details (accessed 18 September 2023).

17 https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/enforcement-and-protection/investment-screening_en

18 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2024/03/04/eu-angola-council-gives-final-greenlight-to-the-eu-s-first-sustainable-investment-facilitation-agreement/

19 https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/7fc51410-46a1-4871-8979-20cce8df0896/library/42115f40-e2ba-4a49-9162-de92098f15bd/details

20 Council of the EU, 2022. Council Conclusions on the EU’s economic and financial strategic autonomy: one year after the Commission's Communication, 2022. Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/04/05/council-adopts-conclusions-on-strategic-autonomy-of-the-european-economic-and-financial-sector/

21 Official Journal of the European Union, 2022. Council Regulation (EU) 2022/1905 of October 6, 2022 amending Regulation (EU) No 269/2014 concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32022R1905

22 Ibid.

1.jpg)