Организация тюркских государств: перспективы развития и риски для Евразийского экономического союза

[To read the article in English, just switch to the English version of the website.]

Живалов Владимир Николаевич — д.э.н., аналитик Центра социально-политических исследований Института развития интеграционных процессов Всероссийской академии внешней торговли.

ORCID: 0000-0001-6827-5754

Чимирис Екатерина Сергеевна — к.п.н., руководитель Центра социально-политических исследований Института развития интеграционных процессов Всероссийской академии внешней торговли, доцент департамента политологии факультета социальных наук и массовых коммуникаций Финансового университета при Правительстве РФ.

ORCID: 0000-0002-9837-8014

Алиев Тимур Мамедович — к.э.н., старший научный сотрудник Института международной экономики и финансов Всероссийской академии внешней торговли.

ORCID: 0000-0003-3545-542X

Для цитирования: Живалов В.Н., Чимирис Е.С., Алиев Т.М. Организация тюркских государств: перспективы развития и риски для Евразийского экономического союза // Современная мировая экономика. Том 1. 2023. № 2 (2).

Ключевые слова: тюркский мир, региональные интеграционные объединения, постсоветское пространство, геополитическая реальность, тюркская интеграция, риски, саммит, торгово-экономическое сотрудничество, Евразийский экономический союз, Центральная Азия.

Аннотация

В статье подвергаются анализу этапы развития Организации тюркских государств (ОТГ) как международной организации. Рассматриваются активные консолидирующие действия Турции по налаживанию экономических связей с независимыми государствами Центральной Азии и изучаются основные направления развития международных экономических отношений стран — государств ОТГ. На основе проведенного сбора и анализа информации делается вывод о том, что в нынешней ситуации очевидна заинтересованность стран ОТГ в расширении сфер влияния. Оценивается современное состояние международных экономических взаимоотношений новых евразийских региональных интеграционных объединений — ОТГ и Евразийского экономического союза (ЕАЭС), появившихся после разрушения единого экономического пространства СССР. В статье раскрыты перспективные направления экономического развития ОТГ, позволяющие рассматривать ее как специфический источник риска для ЕАЭС.

Введение

Очевидной реальностью современной мировой экономики стало смещение центра тяжести от развитых к развивающимся странам. В результате быстрого роста экономических сил развивающихся стран в мире проходит процесс реструктуризации, приводящий к возникновению новых интеграционных партнерств. В последние 30 лет активность Турции на постсоветском пространстве, особенно в странах Центральной Азии (ЦА), привела к созданию международной организации ОТГ. По мнению политолога Р. Сулейманова, «Турция стремится переориентировать республики бывшего СССР на себя и все это вписывается в доктрину пантюркизма: много государств — одна тюркская нация»1.

Появление новых государств на постсоветском пространстве, связанное с процессом распада Советского Союза, значительно снизило влияние России на них. Это породило желание крупных мировых держав войти в геоэкономическое пространство бывшего Советского Союза. Турецкая республика воспользовалась шансом объединить вокруг себя государства, большую часть населения которых представляют тюрки, и стремится при поддержке народов, объединенных культурными и языковыми общностями на постсоветском пространстве, к созданию «тюркского мира». Благодаря инициативе Турции, турецкий вектор стал одним из самых динамичных в Центральной Азии и отдельных регионах России, где проживают тюркские народы.

Процесс становления ОТГ как международной организации, начавшийся в 90-е годы прошлого века, прошел несколько этапов развития.

Первый этап начался после распада СССР с состоявшегося в Анкаре в 1992 году саммита, в котором приняли участие президенты шести государств (Турцию представлял президент Т. Озал, Азербайджан — А. Элчибей, Казахстан — Н. Назарбаев, Кыргызстан — А. Акаев, Узбекистан — И. Каримов, Туркменистан — С. Ниязов). Поскольку встречи были результативными, президенты продолжили практику проведения подобных саммитов. Встречи проводились в 1994, 2001 и 2010 гг. в Стамбуле, в 1995 г. в Бишкеке, в 1996 г. в Ташкенте, в 1998 г. в Астане, в 2000 г. в Баку, в 2006 г. в Анталии.

Вторым этапом сотрудничества стало юридическое оформление организации тюркских государств. В 2009 г. в Нахичевани учрежден Совет сотрудничества тюркоязычных государств (ССТГ, Тюркский совет). Он был создан как межправительственная организация, главной целью которой является содействие всестороннему сотрудничеству между тюркскими государствами. В последующие годы Совет смог институционализировать отраслевое сотрудничество и создать дочерние платформы, такие как Парламентская ассамблея тюркских государств (ТЮРКПА), Международная организация тюркской культуры (ТЮРКСОЙ), Международная тюркская академия и др. В итоговом документе Нахичеванского саммита выражено стремление тюркских государств способствовать укреплению мира, безопасности и стабильности в регионе и мире.

Исторический саммит прошел в Стамбуле в ноябре 2021 г. Он положил начало третьему этапу, на котором Тюркский совет был реорганизован в Организацию тюркских государств (ОТГ). В ходе саммита утвердили Положение о партнерах Организации тюркских государств. Использование потенциала добрососедства, солидарности и сотрудничества в духе равенства, взаимного доверия, взаимного интереса, взаимных консультаций и стремления к развитию в рамках сотрудничества стало основной целью созданной организации. Концепция «Великого Турана» предполагает объединение в одной сверхконфедерации всех тюркоязычных народов (Горохов 2021). Структура открыта для установления конструктивных отношений сотрудничества с третьими странами и международными организациями.

Наиболее значимым событием организации после изменения ее названия на Организацию тюркских государств стало принятие «Концепции тюркского мира до 2040 года». По мнению экспертов, если странам удастся ее реализовать к 2040 г., интеграция тюркского мира будет достигнута. По мнению профессора Международного турецко-казахского университета Д. Томара, «документ, о котором идет речь, содержит пункты, которые обеспечат сотрудничество и единство тюркского мира во всех сферах» (Томар 2021). Девятый саммит ОТГ 2022 года в Самарканде проходил под лозунгом «Новая эра тюркской цивилизации: на пути к общему развитию и процветанию» и имеет большое значение с точки зрения принятых решений и последних посланий.

Официальными языками ОТГ стали азербайджанский, казахский, киргизский и турецкий, а также английский как дополнительный. Если присоединятся новые члены, то языки этих государств также станут официальными языками организации.

Около пятнадцати стран изъявили желание наладить различные формы международного экономического сотрудничества с организацией, что свидетельствует о ее репутации и росте международного влияния (История сегодня… 2021).

Вместе с Турцией и государствами Центральной Азии многонациональный тюркский мир формально включает тюркское население некоторых субъектов Российской Федерации (Чувашия, Башкортостан, Татарстан, Якутия, Республика Крым, Тыва и т.д.), Гагаузии (автономное территориальное образование в составе Республики Молдова) и Синьцзян-Уйгурского автономного района КНР. Район находится на северо-западе Китая и был организован 1955 году, в нем проживает примерно 3640 тыс. уйгуров. Тюркской страной считается также Турецкая Республика Северного Кипра (признана лишь Организацией Исламская конференция) (Мусеибов 2004).

OTГ организована с целью консолидировать народы стран, в которых основное население составляют тюрки, с целью укрепления взаимовыгодного экономического сотрудничества. Турция играет самую активную роль в работе этой региональной международной организации на евразийском пространстве. ОТГ представляет единство ряда государств на этнической основе, от которой отказались многие народы, имеющие общие этнокультурные (славяне, немцы) и языковые (испано-, португало-, персоязычные и т.д.) корни.

Государствами-учредителями ОТГ, кроме Турции и Азербайджана, являются участники другого интеграционного объединения ЕАЭС — Казахстан и Кыргызстан. В дальнейшем к этой организации присоединились и другие сраны ЦА. В октябре 2019 г. полноправным членом стал Узбекистан. На саммите, состоявшемся в ноябре 2021 г., к организации присоединился Туркменистан. Венгрия и частично признанная Турецкая Республика Северного Кипра получили статус члена-наблюдателя 2.

Важнейшую роль в ОТГ играет Турция, которая стремится объединить народы, используя идею воссоздания прототипа Османской империи — «Тюркского мира» в современных исторических условиях. «Тюркский мир» изначально мыслился как костяк более пространственной общности — Турана, под которым следует понимать всю совокупность уральских и алтайских этносов — финно-угров, тунгусо-маньчжуров, тюрков, монголов, а временами корейцев и японцев. Последних рассчитывают притянуть к проекту «Тюркский мир», но это скорее всего дело будущего.

В Турции с момента прихода исламистской Партии справедливости и развития (ПСР) к власти с очевидным постоянством поднимался вопрос о формировании коллективных вооруженных сил, но, как показала вторая Карабахская война, реальностью может стать только лишь военно-политический альянс Турции и Азербайджана. Хотя президент Турции Р. Эрдоган многократно говорил, что грезит о «появлении на карте шести государств одной нации» (Иванов 2022).

Основным решающим органом в ОТГ является Совет глав государств, который возглавляет страна, принимающая на себя председательство (ротация проходит в алфавитном порядке). Другими рабочими органами являются Совет министров иностранных дел, Совет старейшин, Комитет старших должностных лиц.

Министры иностранных дел государств-членов регулярно встречаются на саммитах для обсуждения вопросов, представляющих взаимный интерес. Встречи министров иностранных дел ОТГ, носящие неформальный характер, проходят в рамках сессии Генеральной Ассамблеи ООН.

Комитет старших должностных лиц ОТГ состоит из высокопоставленных должностных лиц министерств иностранных дел и соответствующих государственных учреждений стран-членов. Комитет собирается регулярно, как правило, перед заседаниями Совета министров иностранных дел. В его обязанности входит координация всей деятельности Совета, подготовка официальных документов, представляемых на подпись, и проведение аналогичной работы по вопросам, относящимся к внутренним делам. Комитет на регулярной основе собирался 30 раз и 7 раз по специальным случаям с особой повесткой дня.

Перспектива развития ОТГ

С целью формирования тюркской идентичности Турция инициировала создание целого ряда организаций, причем не только государственных, частно-государственных, но и частных.

В целях развития и укрепления межпарламентского сотрудничества 21 ноября 2008 года Стамбульским соглашением создана Парламентская ассамблея тюркских государств (ТЮРКПА). Организация призвана развивать политический диалог между государствами-членами посредством парламентской дипломатии, гармонизировать национальное законодательство государств-членов и укреплять совместную деятельность, в том числе по расширению внешнеэкономических связей, реализации совместных бизнес-проектов, нахождению путей решения различных экономических проблем тюркского мира.

Важной вехой в развитии тюркской идентичности стало создание Международной организации тюркской культуры (ТЮРКСОЙ), которая берет свое начало на встречах 1992 года. Организация представляет собой союз тюркоязычных стран, основной целью которого является «налаживание сотрудничества между тюркоязычными народами для сохранения, развития и передачи будущим поколениям совместных материальных ценностей и культурных памятников тюркских народов». 3 мая 2023 года в Библиотеке Первого Президента Республики Казахстан состоялся международный круглый стол «ТЮРКСОЙ — 30 лет: итоги и перспективы», организованный совместно с Международной организацией тюркской культуры 3.

Особое место в организации тюркского мира заняла Международная тюркская академия, функционирующая в Казахстане с 2010 года. За эти годы было установлено тесное взаимодействие с ТЮРКСОЙ, ТЮРКПА, Тюркским советом, IRCICA (Научно-исследовательским центром исламской истории, искусства и культуры). Членами академии являются Азербайджан, Казахстан, Кыргызстан и Турция, Венгрия имеет статус наблюдателя. Академия занимается научно-исследовательской работой, изданием книг и журналов, проведением международных форумов и конференций с известными учеными, а также научными работами по тюркологии 4.

Созданный в 2013 году Союз тюркских университетов продвигает различные формы сотрудничества между университетами государств. Количество его вузов-членов с 2014 года по настоящее время выросло с 14 до 22. У Союза есть много направлений деятельности — Орхунская программа обмена, Спартакиада Союза и Студенческий совет. В ходе развития и реализации данных программ с 2014 года было организовано пять встреч на уровне ректоров и проректоров и три генеральных собрания. В 2019 году, в ходе Четвертой Генеральной Ассамблеи Союза тюркских университетов, организованной Международным казахско-турецким университетом имени Ходжи Ахмеда Ясави (Университет Ахмеда Ясави), в Союз были приняты в качестве новых членов Турецкий университет Гази, Университет Нигде Омера Халисдемира, Каппадокийский университет и Сегедский университет Венгрии 5.

Фонд Тюркской культуры и наследия со штаб-квартирой в Баку был организован на саммите Тюркского совета в Бишкеке в августе 2012 года. Деятельность фонда направлена на исследование, защиту, пропаганду, продвижение культуры и наследия тюркоязычных народов. В своей работе Фонд использует опыт других тюркоязычных и международных организаций и налаживает сотрудничество с ними 6.

Специальным соглашением 20 октября 2011 года в Алматы создан Деловой совет тюркоязычных стран. Деловой совет нацелен на инициирование и контроль многосторонних действий в рамках международного экономического сотрудничества на основе принципа взаимопомощи и поддержки в соответствии с приоритетами, описанными в соглашении, и институционализации существующих механизмов сотрудничества в области взаимных инвестиций и торговли. Под эгидой Делового совета было проведено 6 заседаний и 10 международных бизнес-форумов, в которых приняли участие более 500 предпринимателей. Организованы технические визиты для инвесторов, встречи за круглым столом для предпринимателей государств-членов, программы обмена опытом между национальными торгово-промышленными палатами7.

Тюркская торгово-промышленная палата (TCCI) со штаб-квартирой в Стамбуле была официально создана в 2019 году и состоит из торгово-промышленных палат и бизнес-сообществ государств-членов и государств-наблюдателей. TCCI является важным механизмом международного экономического сотрудничества, а также реализации устойчивых бизнес-программ и проектов для увеличения показателей международной торговли между государствами-членами. Планируется создать правовую инфраструктуру и для Торгово-промышленной палаты Трабзона, в которую входят автомобильные и транспортные компании, с целью направления и внедрения ее представителей в постоянную структуру, которая будет непрерывно работать для дальнейшего развития международных экономических отношений частного сектора тюркского мира.

За короткое время с момента своего создания TCCI удалось организовать масштабные бизнес-форумы в Ташкенте и Баку с участием государственных деятелей и более 500 бизнесменов. Например, в 2020 г. в рамках усилий стран Тюркского совета TCCI подготовила предложения, направленные на предотвращение нежелательных последствий эпидемии COVID-19. Кыргызская торгово-промышленная палата (Кыргызская ТПП) и Союз палат и товарных бирж Турции договорились о сотрудничестве в технической помощи по укреплению Кыргызской ТПП. В настоящее время прорабатывается проведение масштабного бизнес-форума 8.

Весьма заметна в этом интеграционном процессе образовательно-культурная сфера. Можно выделить специально созданные организации, такие как Тюркское агентство по сотрудничеству и развитию, международная Организация изучения тюркской культуры, Институт имени Юнуса Эмре. Перечень проводимых ими мероприятий и разнообразных программ впечатляет: проведение общетюркских фестивалей, строительство мечетей и больниц, выделение грантов студентам, разработка единых учебников по литературе, географии, истории. При этом Турция осознанно поддерживает репутацию прогрессивного, прозападно настроенного государства, формируя таким образом мировоззрение у молодого поколения тюркского населения.

Видима активность Турции в таких сферах, как торгово-экономическая и транспортно-логистическая. Особенно активно ее участие в строительстве трубопроводных путей, международных автомобильных трасс и железных дорог. Турция обеспечивает прохождение через свою территорию всего многообразия топливно-энергетических ресурсов и различных видов сырья, потребляемых современным производством, в страны средиземноморского бассейна и ЕС. Это отвечает экономическим интересам восточноазиатских стран, таких как Китай, южноазиатских стран, таких как Индия, а также стран Южного Кавказа и ЦА и активно поддерживается западноевропейскими странами и США.

Созданную ОТГ следует воспринимать как попытку Турции создать новый альянс — альтернативу Евразийскому экономическому союзу. В ближайшее десятилетие странами ОТГ с населением в 173 млн человек намечено создать рынок инвестиций, рабочей силы, товаров и услуг.

Современной особенностью дальнейшего развития ОТГ являются попытки Турции вовлечь тюркские государства не только во внешнеполитическую, но и военно-политическую деятельность. Например, глава МИД Турции высказывает мнение, что тюркские страны обязаны инициировать развитие новых военно-политических процессов, а не только реагировать на них. Так, в настоящее время остро стоит вопрос создания турецкой военной базы в Азербайджане, обсуждается дальнейшее расширение сотрудничества в военно-технической сфере, планируются военные маневры и учения. Около 10 лет вынашивается идея создания организации собственных внутренних сил, обладающих военным статусом и подчиняющихся Тюркскому совету. Однако по мнению востоковеда, эксперта РСМД К. Семенова: «Амбиции Турции несомненны, но речи об объединенной тюркской армии пока нет» (Семенов 2022).

Прошедший в 2022 году в Узбекистане Саммит ОТГ продемонстрировал уверенность государств — членов ОТГ в дальнейшем углублении и развитии международного сотрудничества не только в экономической, но и культурной сфере, с учетом языка и народных традиций тюркского народа.

В рамках ОТГ учреждены Банк развития, Тюркский инвестиционный фонд, а также соглашение по упрощению таможенных процедур. Предложено создать фонд венчурных инициатив с целью развития современных высоких технологий, цифровизации и образования. Поддержано строительство железных дорог Узбекистан—Кыргызстан—Китай и Термиз—Мазари-Шариф—Кабул—Пешавар, что значительно увеличит пропускную способность железных дорог Баку—Тбилиси—Карс. Планируется расширение транспортных связей между Европой и Азией, а также общая диверсификация инфраструктуры всего транспортного сообщения.

В целях обеспечения близкой координации и взаимодействия по вопросам безопасности государства — члены ОТГ договорились о проведении регулярных консультаций по развитию глубоких отношений в оборонной промышленности и военной сфере.

Выгодное стратегическое положение Турции как страны транзита в новых транспортных коридорах Восток—Запад и Север—Юг делает ее главным бенефициаром за счет приобретения в России и странах ЦА недорогих энергоносителей, а в странах ЕС — современных технологий. Имеется возможность получения Турцией в качестве преференции инвестиций из Китая и соответственно некоторую лояльность США и ЕС к развитию ее отношений со странами ЦА.

Вместе с тем сохраняются преграды по возрождению тюркского мира. Например, в Турции курды составляют существенную часть населения — более 23%, в Казахстане почти 20% граждан — это русские, курды, украинцы и представители других национальностей. В государствах постсоветского пространства существуют этнические группы, не имеющие никакого отношения к тюркской группе.

С весьма большей осторожностью относятся государства ЦА к привлечению их стран к другим внешнеполитическим союзам. К тому же, их интересы в ОТГ ограничены торгово-экономическим взаимодействием, логистическими решениями, сотрудничеством в гуманитарной сфере, включая вопросы культуры и религии.

В ОТГ имеется немало внутрирегиональных проблем со странами ЦА, например, заметна не только внутриполитическая, но и экономическая нестабильность. Существует много проблем и в социальной сфере, где довольно высок уровень безработицы. Общество сотрясают межклановые конфликты и коррупция, присутствуют реальные угрозы, связанные с безопасностью границ, наркотрафиком, исламским радикализмом. Страны ЦА лихорадят не только межстрановые разногласия, связанные с конкуренцией за энергетические и водные ресурсы, но и постоянные этнотерриториальные инциденты Узбекистана, Таджикистана и Кыргызстана. По мнению экспертов, серьезной внешней угрозой для стран ЦА является «фактор Афганистана», который может превратиться в одно из укреплений радикального исламизма.

ЕАЭС и ОТГ

В настоящее время на обширных территориях сформировались и существуют вдоль условной границы между Европой и Азией два евразийских альянса — ОТГ и ЕАЭС. Формально ОТГ не является союзом, поскольку в организации отсутствует традиционное оформление отношений. Из членов ЕАЭС в ОТГ присутствуют Казахстан и Кыргызстан, что служит важным фактором, способным одновременно как порождать противоречия, так и сдерживать какие-либо «резкие действия» всех участников ЕАЭС и ОТГ.

Очевидно, что перспективы взаимодействия ЕАЭС и ОТГ будут зависеть от российско-турецких отношений, т.к. Россия и Турция являются крупнейшими странами в этих организациях. Россия является основой ЕАЭС, в ОТГ, как организационно, так и в производственном и военном контексте, господствует Турция. Следует также отметить, что Казахстан был одним из главных инициаторов евразийской и тюркской интеграции. С момента создания в 2015 г. ЕАЭС участие в саммитах тюркоязычных государств первых лиц Казахстана и Кыргызстана было постоянным. В сентябре 2015 года участие в пятом саммите Совета сотрудничества тюркоязычных государств принимал президент Кыргызстана А. Атамбаев и Президент Казахстана Н. Назарбаев. В шестом саммите, который состоялся в сентябре 2018 г., участвовали Президент Казахстана Н. Назарбаев и Кыргызстана С. Жээнбеков. В октябре 2019 г. в Баку состоялся седьмой саммит, на котором присутствовали президент Казахстана Н. Назарбаев и Кыргызстана С. Жээнбеков. Стамбульский саммит 12 ноября 2021 г. проходил уже с участием президента Казахстана К. Токаева и президента Кыргызстана С. Жапарова.

Вся деятельность ОТГ позволяет говорить о том, что Турция довольно тщательно и систематически старается воплощать идеи по расширению сферы собственной национальной идеи о консолидации тюркских народов и проникновению неоосманской идеологии, которая противопоставляется евразийской культуре, и тем самым стремится энергично конкурировать с интеграционной инициативой России.

По мнению политолога, эксперта М. Бурды, «опыт ОТГ, конечно, мог бы быть использован в рамках Евразийского экономического союза. … В отличие от тюркского мира, где есть этническая и религиозная формы идентичности, в рамках евразийского партнерства таких скреп практически не осталось. Поэтому на сегодняшний день не видится предпосылок для запуска в рамках ЕАЭС каких-то общих процессов» (Крек Н. 2022).

По мнению экспертов, «Турцией активно используется против России полный арсенал оружия “мягкой силы”, включая сферы культуры и образования, а также энергичное присутствие в русскоязычном интернет-пространстве» (Аватков, Бадранов 2013). Заметно активизировалась она и внутри России на фоне культурных, гуманитарных и научных проектов в 1990-х гг., сразу после распада СССР. Так, в Татарстане была учреждена Ассамблея тюркских народов, активно продвигающая отделение национальных автономий от Российской Федерации. «Якутия, Татарстан и Башкирия открыто претендовали на статус национальных независимых государств, а в Якутии даже готовились создать собственную армию и ввести визовый режим для остальных российских граждан» (Горохов 2021).

Экспертные исследования говорят, что именно Турцией предлагаются новые идеи если не отделения этих автономий от России, то по крайней мере выхода к границам постсоветских тюркских республик. В качестве примера приводят идею создания «Тюркского коридора», ради которого часть Оренбургской области должна быть передана Татарстану или Башкирии с тем, чтобы эти республики смогли напрямую граничить с «братьями по языку и вере» казахами. «Это полностью совпадает с планами идеологов «Великого Турана», видящими в составе этой империи не только тюркские автономии Российской Федерации, но и весь Северный Кавказ, Калмыкию, Крым, Дагестан, Астраханскую, Волгоградскую, Курганскую, Ростовскую, Саратовскую, Самарскую, часть Свердловской, Оренбургскую, Челябинскую области, Краснодарский, Красноярский и Ставропольский края, и едва ли не всю Сибирь» (Горохов 2021).

Для России и соответственно ЕАЭС создание ОТГ представляет определенную опасность. Если до сих пор упор делался на культурную и гуманитарную сферу, то новое название является шагом в сторону еще более обязывающей структуры, члены которой могут быть связаны «механизмами оперативного принятия решений», что подчеркнул на саммите глава турецкого МИД М. Чавушоглу 9. На вопрос, для чего Турции нужен новый статус организации, ответил турецкий политолог Керим Хас: «Раджеп Эрдоган очень заинтересован в расширении зоны влияния Турции. В Средней Азии, где живут братские туркам тюркские народы, делать это проще и логичнее всего. Во-вторых, нужно как можно больше рычагов давления на Россию. Увеличивая свое влияние в приграничных с Россией странах, Турция получает сильные позиции в переговорах по всем вопросам. Их становится немало. К примеру, это Сирия и Ливия, и различные экономические проекты, и ситуация на Южном Кавказе» (Горохов 2021).

И хотя к этому вопросу ряд тюркских государств Центральной Азии относится скептически, новое положение членов организации не столько культурной, сколько политической направленности, обязывает. Тем более, что у Турции в ОТГ в самое ближайшее время может появиться союзник. Именно президент Р. Эрдоган предложил сделать полноправным членом организации частично признанную Турецкую Республику Северного Кипра, что автоматически приведет к ее признанию всеми государствами, входящими в ОТГ.

По мнению востоковеда, советника Российской национальной службы экономической безопасности» (РНСЭБ), члена экспертного совета комитета ГД по делам СНГ, евразийской интеграции и связям с соотечественниками А. Савельева, «потакание российских чиновников безмерным амбициям Анкары и национализму в сочетании с пантюркизмом в бывших советских республиках может не только привести к краху и без того вялых интеграционных структур, но и создать на границах России очередной очаг напряженности…..Время пустых фраз и самоуспокоения для России прошло…» (Савельев 2022).

По мнению отдельных экспертов, Турция, несмотря на то, что является главным носителем идеи этногеографического, культурного, экономического, политического и военного объединения, неминуемо встретится с интересами России и Китая. Россия же, в свою очередь, уже делала заявление о том, что центр тюркского мира находится на российском Алтае, то есть вне Турции. По мнению, старшего научного сотрудника ИМЭМО РАН В. Надеина-Раевского, «Китай относится к консолидации тюркского мира категорически отрицательно. Официальный Пекин неоднократно возмущался тем, что Турция “лезет не в свои дела”. Анкара ведь претендует на то, что она выступает защитницей интересов всех тюрок: и крымских татар, и жителей Синьцзян-Уйгурского автономного района КНР»10.

По мнению А.В. Чекрыжова, руководителя Сектора изучения мировой экономики и евразийских интеграционных процессов Центра геополитических исследований «Берлек-Единство», «включение России, КНР, а тем более обеих стран в состав ОТГ до сих пор признается маловероятным. Анкара может единолично определять векторы развития ОТГ, исходя из собственных интересов, но включение в эту систему России или КНР нарушит статус-кво, и любые решения придется выносить уже исходя из консенсуса сторон. В связи с этим придется сделать выбор среди двух векторов развития организации. Первый заключается в игнорировании “невыгодных” для Турции тюркских народов России и Китая. В таком случае организация достигнет максимального результата довольно быстро. Максимум будет выражаться в совместных культурно-гуманитарных проектах стран-участниц, наращивании торгово-экономического сотрудничества. Второй вариант развития предполагает сближение и интеграцию проекта с Россией и Китаем. В таком случае Турция потеряет гегемонию, но откроет дверь в Большую Евразию с учетом сопряжения ОТГ с ШОС, ЕАЭС и транспортными проектами КНР. Конечно, такой сценарий сегодня кажется не реальным, но времена меняются» (Чекрыжов 2022).

Торгово-экономическое сотрудничество ЕАЭС с ОТГ

Реализуемый Азербайджаном, Казахстаном, Кыргызстаном, Узбекистаном, Туркменистаном (а также Венгрией и Турецкой Республикой Северного Кипра в качестве наблюдателей) совместно с Турцией проект ОТГ по развитию интеграции несет для ЕАЭС в целом и для России в частности определенные риски. Например, тюркоязычные страны СНГ используют различные возможности для повышения своей конкурентоспособности и диверсификации торгово-экономических связей, в том числе за счет сотрудничества в рамках ОТГ. Не исключено, что расширяющаяся интеграция в субрегионе будет использоваться в целях ослабления политико-экономического влияния России (и Китая).

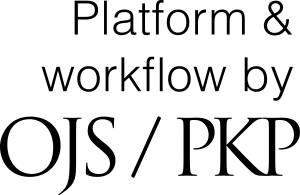

В 2016 г. было зафиксировано ощутимое сокращение объемов товарного экспорта ЕАЭС в страны ОТГ (Азербайджан, Турцию и Узбекистан) с 26,8 млрд долл. США (в 2015 г.) до 19,4 млрд долл. США. В целом, во второй половине 2010-х гг. позитивная динамика отмечалась до 2019 г. включительно, когда показатель достиг 32,8 млрд долл. США. В 2020 г. он сократился на 15,2% до 27,8 млрд долл. США. Стоимостный объем товарного экспорта ЕАЭС в ОТГ за 12 месяцев 2021 г. составил 41,5 млрд долл. США, увеличившись на 49,2% по сравнению с предыдущим годом и существенно превысив «доковидный» уровень (2019-го года). В 2022 г. произошел резкий рост экспортных поставок из ЕАЭС в страны ОТГ — до 80 млрд долл. США.

В 2015–2016 гг. объем товарного импорта ЕАЭС из Турции изменился с 7,5 до 5,8 млрд долл. США. В 2016–2019 гг. он неуклонно повышался, в 2020 г. снизился на 3,2%, а в 2021–2022 гг. установился на уровне 13,4 и 18,4 млрд долл. США, соответственно (см. рис. 1).

Рисунок 1. Динамика внешней товарной торговли ЕАЭС со странами — членами Организации тюркских государств* в 2015-2022 гг.11

Примечание: * – без учета государств — членов ЕАЭС (Казахстана и Кыргызстана) в составе ОТГ.

Источники: ЕЭК, ITC Trade Map

Основа товарного экспорта ЕАЭС в страны ОТГ – продукция топливно-энергетического профиля, металлы и изделия из них, продовольственные товары и сельскохозяйственное сырье (кроме текстильного). В импорте ЕАЭС из стран Организации тюркских государств преобладает аграрная продукция, текстиль, текстильные изделия и обувь, а также продукция химической промышленности, машины, оборудование и транспортные средства (см. Таблицу 1).

Таблица 1. Товарная структура внешней торговли ЕАЭС со странами — членами Организации тюркских государств* в 2015, 2019 и 2022 гг., в % к итогу12

|

Коды ТН ВЭД |

Товарная группа |

Экспорт товаров ЕАЭС в страны ОТГ |

Импорт товаров ЕАЭС из стран ОТГ |

||||

|

2015 |

2019 |

2022 |

2015 |

2019 |

2022 |

||

|

01-24 |

Продовольственные товары и сельскохозяйственное сырье (кроме текстильного) |

12,5 |

14,1 |

12,1 |

30,9 |

26,8 |

22,1 |

|

25-27 |

Минеральные продукты |

21,4 |

35,2 |

61,0 |

5,6 |

4,0 |

3,7 |

|

27 |

Топливно-энергетические товары |

20,6 |

33,9 |

60,2 |

4,4 |

2,7 |

2,8 |

|

28-40 |

Продукция химической промышленности, каучук |

5,0 |

5,3 |

4,5 |

10,9 |

12,0 |

15,1 |

|

41-43 |

Кожевенное сырье, пушнина и изделия из них |

0,0 |

0,0 |

0,0 |

0,7 |

0,6 |

0,5 |

|

44-49 |

Древесина и целлюлозно-бумажные изделия |

3,1 |

3,2 |

2,6 |

1,2 |

0,8 |

1,5 |

|

50-67 |

Текстиль, текстильные изделия и обувь |

0,3 |

0,4 |

0,2 |

19,5 |

23,9 |

22,4 |

|

71 |

Драгоценные камни, металлы и изделия из них |

0,1 |

0,2 |

1,3 |

0,5 |

0,3 |

0,5 |

|

72-83 |

Металлы и изделия из них |

21,7 |

16,7 |

14,8 |

6,1 |

6,6 |

6,7 |

|

84-85 |

Машины и оборудование |

2,0 |

4,5 |

2,0 |

12,5 |

12,4 |

17,5 |

|

86-89 |

Транспортные средства |

1,9 |

2,7 |

0,9 |

5,5 |

8,3 |

6,2 |

|

90-92 |

Технические инструменты и аппаратура |

0,2 |

0,4 |

0,1 |

0,9 |

0,4 |

0,5 |

|

68-70, |

Другие товары |

31,8 |

17,2 |

0,4 |

5,8 |

4,0 |

3,3 |

Примечание: * – без учета государств — членов ЕАЭС (Казахстана и Кыргызстана) в составе ОТГ.

Источник: ITC Trade Map.

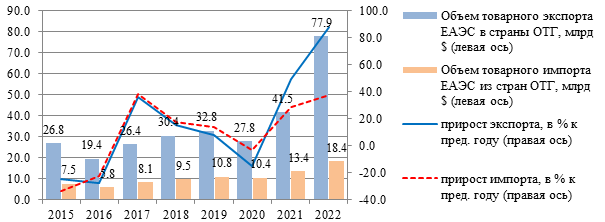

По данным ЕЭК (на основе официальных данных центральных банков стран — членов ЕАЭС), в период с 2015 г. максимальный объем прямых иностранных инвестиций (ПИИ), привлеченных в ЕАЭС из стран Организации тюркских государств, пришелся на 2021г. Масштабы исходящих ПИИ из ЕАЭС в страны ОТГ были значительными в 2015–2016 гг. и составили 1,5 и 1,1 млрд долл. США соответственно (см. рис. 2).

Рисунок 2. Инвестиционное взаимодействие ЕАЭС со странами — членами Организации тюркских государств** в 2015-2022 гг. (потоки ПИИ)

Примечания: * – без учета данных по России; ** – без учета государств — членов ЕАЭС (Казахстана и Кыргызстана) в составе ОТГ.

Источник: ЕЭК13.

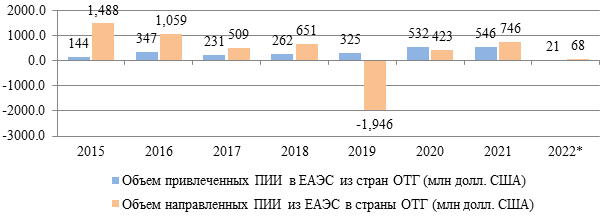

Объемы накопленных ПИИ, привлеченных в ЕАЭС из стран — членов ОТГ, увеличились с 1,5 млрд долл. США в 2015 г. до 5,3 млрд долл. США в 2021 г., а накопленные исходящие ПИИ ЕАЭС в страны — члены Организации тюркских государств изменились с 7,9 до 7,8 млрд долл. США. В 2022 г., без учета данных по Кыргызстану и России, накопленные капиталовложения стран ОТГ в ЕАЭС составили 1,8 млрд долл. США, а запасы исходящих ПИИ из ЕАЭС в ОТГ — 0,5 млрд долл. США (см. рис. 3).

Рисунок 3. Инвестиционное взаимодействие ЕАЭС со странами — членами Организации тюркских государств** в 2015, 2021 и 2022 гг. (накопленные ПИИ)

Примечания: * – без учета данных по Кыргызстану (в 2022 г. – без учета данных по Кыргызстану и России); ** – без учета государств-членов ЕАЭС (Казахстана и Кыргызстана) в составе ОТГ.

Источник: ЕЭК14.

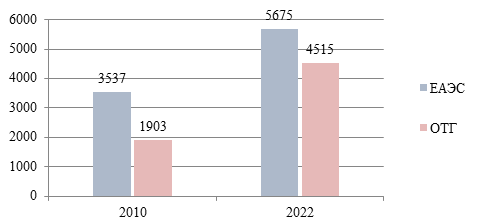

Масштабы экономик государств — членов ОТГ ощутимо выросли. За 2010–2022 гг. совокупный ВВП по ППС стран — участниц ОТГ изменился с 1,9 до 4,5 трлн долл. США. По отношению к ВВП ЕАЭС показатель увеличился с 54% до 80%, т. е. наблюдается заметное сближение экономических потенциалов двух интеграционных объединений (см. рис. 4).

Рисунок 4. Экономический потенциал ЕАЭС и Организации тюркских государств в 2010 и 2022 гг. (величина совокупного ВВП по ППС; млрд долл. США)15

Источник: МВФ.

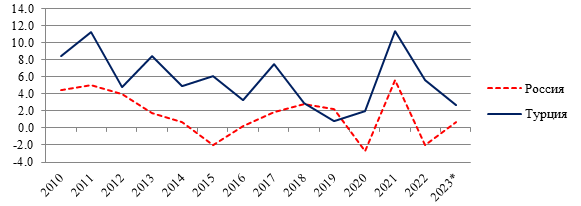

Торгово-экономический потенциал ОТГ в первую очередь формируется за счет ведущего игрока в субрегионе — Турции. Благодаря структурным реформам, осуществляемым с начала 2000-х гг., которые сопровождались масштабными внутренними инвестициями в инфраструктуру и качественной перестройкой промышленности, улучшением инвестиционного климата в стране и ростом внешних заимствований, Турция совершила скачок в социально-экономическом развитии. В последнее десятилетие турецкая экономика входила в число наиболее быстро развивающихся экономик в мире, значительно опережая темпы роста российской экономики. В 2010–2022 гг. средние темпы прироста ВВП Турции составили 6,0% ежегодно, а в России они равнялись 1,7% (см. рис. 5). При всех своих объективных различиях российская и турецкая экономики становятся сопоставимыми. Турция вполне обоснованно претендует на роль геополитического лидера в ближневосточном регионе, вовлекая в сферы своих экономических интересов страны Южного Кавказа и Центральной Азии.

Рисунок 5. Темпы экономического роста в России и Турции в 2010-2023 гг. (прирост реального ВВП по ППС; в % к предыдущему году)16

Примечание: * – прогноз МВФ.

Источник: составлено авторами с использованием данных национальных статистических ведомств и данных МВФ.

В рамках ОТГ проводится работа по организации инвестиционного фонда для оказания финансовой помощи малому и среднему бизнесу в тюркоязычных государствах. Вопрос создания фонда впервые обсуждался министрами экономики стран — членов Совета сотрудничества тюркоязычных государств (переименован в ОТГ) в 2012 г. в Баку. Деятельность фонда будет способствовать активизации инвестиционной деятельности между странами, в том числе экспансии турецкого капитала в тюркоязычные страны СНГ, обладающие большим потенциалом относительно дешевой рабочей силы.

Пока уровень инвестиционного присутствия Турции в этих странах незначителен. Например, по состоянию на 1 апреля 2023 г. объем накопленных турецких инвестиций в Казахстане достигал 1,74 млрд долл. США (из них ПИИ — 1,26 млрд долл. США), что по отношению к суммарным инвестициям, накопленным в казахстанской экономике, составляло всего 0,7%17.

В декабре 2022 года таможенные службы двух стран успешно осуществили мультимодальную перевозку eTIR узбекским перевозчиком по маршруту из Узбекистана (т/п Арк-Булак/Авиаюклар) в Азербайджан (т/п Аэропорт Баку/Грузовой терминал Баку) с использованием электронной гарантии eTIR на платформе ЕЭК ООН. Ранее в рамках OTГ в сотрудничестве с Международным союзом автомобильного транспорта (IRU) был запущен проект «цифровой МДП» между Казахстаном и Узбекистаном, который в марте 2022 года был распространен на Кыргызстан. Все это свидетельствует о приверженности государств-членов к практическому сотрудничеству и продвижению цифровизации транспортных и транзитных процедур.

На самаркандском саммите 2022 года с целью облегчения не только информационного обмена о перемещении транспортных средств, но и товаров таможенные структуры государств — членов ОТГ подписали соглашение «О создании упрощенного таможенного коридора между правительствами Организации тюркских государств».

Посредством транспортных коммуникаций появляются возможности организовать через территории стран ОТГ прямой маршрут для транзита грузов из Европы в Китай и в обратном направлении, что может создавать конкуренцию некоторым проектам по формированию транспортных коридоров на евразийском пространстве.

В странах ОТГ активно продолжается совместная деятельность по усилению региональной интеграции путем упрощения, модернизации, стандартизации и гармонизации таможенных процедур, дальнейшего применения цифровых инструментов в таможне, обмена передовым опытом и проведения программ наращивания потенциала по представляющим взаимный интерес направлениям. Планируется продолжить реализацию проекта «Караван-сарай», который повысит конкурентоспособность и привлекательность Транскаспийского международного среднего коридора Восток—Запад за счет обеспечения бесперебойной работы таможенно-пограничных пунктов пропуска.

Заключение

Подводя итоги, следует отметить, что взаимодействие между тюркоязычными государствами в течение последних тридцати лет развивается довольно успешно. ОТГ стремится активно участвовать как в экономической, так и других сферах деятельности стран ЦА. Организация серьезно начинает конкурировать с ЕАЭС, ОДКБ и ШОС, что противоречит интересам евразийской экономической интеграции и в первую очередь России. С уверенностью можно предположить, что влияние ОТГ на страны ЦА и конкуренция между ЕАЭС и ОТГ будет усиливаться. ОТГ способна противопоставить свою экономическую заинтересованность внешнеэкономическим интересам ЕАЭС, однако, она вряд ли выдержит подобную конкуренцию и в первую очередь из-за того, что экономические связи стран ЕАЭС, таких как Казахстан и Кыргызстан, во многом гораздо глубже налажены с Россией, чем с остальными странами ОТГ. Углубление интеграции ОТГ и усиление турецкого влияния в странах ЦА может привести к конфликту интеграционных процессов этих стран в ЕАЭС. При этом противоречия, возникающие из-за членства государств ОТГ в других блоках, маловероятны. Серьезным риском для перспектив развития евразийской интеграции остается укрепление торгово-экономических отношений между странами — членами ОТГ за счет использования упрощенного таможенного коридора и транзитного потенциала.

Однако ОТГ и ЕАЭС могут найти точки соприкосновения и плодотворно сотрудничать друг с другом по многим вопросам как в области экономики, так и политики. Важно найти определенный баланс интересов между ОТГ и ЕАЭС в системе организации таможенного регулирования и внешнеэкономической деятельности в целом, а в будущем, возможно, и в политике. Все это потребует проведения регулярных переговоров между участниками двух организаций в полноценном формате с целью согласования внешнеэкономических интересов каждой страны-участницы. Непрерывные интеграционные процессы в ОТГ ставят перед ЕАЭС вопрос о целесообразности создания единой программы обеспечения экономической безопасности с целью снижения возникающих рисков.

Библиография

Аватков В.А., Бадранов А.Ш. «Мягкая сила» Турции во внутренней политике России // Право и управление. ХХI. 2013. № 2(27). С. 5–11.

Васильева С. А. ЕАЭС и Тюркский совет: перспективы взаимодействия // Известия Уральского федерального университета. Сер. 3, Общественные науки. 2018. Т. 13. № 3 (179). С. 184–192.

Горохов А. Великий Туран от Средиземного моря до моря Лаптевых // Еженедельник Звезда. 2021. 2 дек. // https://zvezdaweekly-ru.turbopages.org/zvezdaweekly.ru/s/news/202111251031-s9FR5.html.

Договор о Евразийском экономическом союзе от 29 мая 2014 года.

Евразийская экономическая комиссия. Департамент статистики // https://eec.eaeunion.org/comission/department/dep_stat/tradestat/analytics/

Иванов С. К итогам саммита Организации тюркских государств // Международная жизнь. 2022. 14 нояб. / https://interaffairs.ru/news/show/37800

История, сегодня и планы на будущее — интервью с Генеральным секретарем Организации тюркских государств // https://kun.uz/uz/news/2021/12/21/tarix-bugun-va-kelgusi-rejalar-turkiy-davlatlar-tashkiloti-bosh-kotibi-bilan-suhbat.

Крек Н. Тюркская история и геополитические амбиции Анкары – что между ними общего? // https://www.ritmeurasia.org/news--2022-08-12--tjurkskaja-istorija-i-geopoliticheskie-ambicii-ankary-chto-mezhdu-nimi-obschego-61414.

МВФ // https://www.imf.org/

Международный фонд тюркской культуры и наследия // https://www.trend.az/tags/45715/.

Мусеибов М., Алиева Е. География Тюркского Мира. Баку, 2004. 110 С.

Нахичеванское соглашение о создании Совета сотрудничества тюркоязычных государств (г. Нахичевань, 3 октября 2009 года) // https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=30486433&pos=4;-106#pos=4;-106

Озимко К. Геополитические амбиции Турции в Средней Азии. Как пантюркизм сопрягается с евразийской интеграцией // https://www.sonar2050.org/publications/geopoliticheskie-ambicii-turcii-v-sredney-azii/

Организация тюркских государств. Официальный сайт // https://turkicstates.org/

Распоряжение ЕЭК в соответствии с Распоряжением Евразийского межправительственного совета от 1 февраля 2019 года №3 «О макроэкономической ситуации в государствах – членах Евразийского экономического союза и предложениях по обеспечению устойчивого экономического развития»

Решение Высшего Евразийского экономического совета от 26 декабря 2016 года № 18 «Об Основных направлениях международной деятельности Евразийского экономического союза на 2017 год» // https://docs.eaeunion.org/ru-ru.

Савельев А. Получится ли у Эрдогана Великий Туран? Согласна ли с этим Россия? // Регнум. 2022. 26 мая / https://regnum.ru/news/polit/3602083.html.

Семенов К. Турция не планирует создавать тюркскую армию //ИАЦ. 2022. 19 окт. / https://ia-centr.ru/experts/kirill-semenov/turtsiya-ne-planiruet-sozdavat-tyurkskuyu-armiyu/

Союз тюркских университетов // https://www.turkkon.org/en/isbirligi-alanlari/education_4/turkic-university-union_14.

Токаев ратифицировал соглашение об условиях размещения Тюркской академии в Казахстане // https://informburo-kz.turbopages.org/informburo.kz/s/novosti/tokaev-ratificiroval-soglashenie-ob-usloviyah-razmesheniya-tyurkskoj-akademii-v-kazahstane.

Томар Д. Исторический поворотный момент: «Концепция тюркского мира до 2040 года» // Turkish Forum. 2021. 19 нояб. // https://www.turkishnews.com/ru/content/2021/11/19/исторический-поворотный-момент-кон/

Турецкое агентство по сотрудничеству и координации (TİKA) // https://www.turkkon.org/en.

Турция является одним из наиболее приоритетных торгово-экономических и инвестиционных партнеров Казахстана // https://dknews.kz/ru/ekonomika/277835-turciya-yavlyaetsya-odnim-iz-naibolee-prioritetnyh

Тюркские страны создали новые механизмы для роста товарооборота // https:// www.aa.com.tr/ru5.

Тюркский деловой совет // https://www.turkkon.org/en/isbirligi-alanlari/economic-cooperation_2/turkic-business-council-and-business-forums_9.

Тюркское НАТО станет проблемой для России и Китая // https://rosbalt-ru.turbopages.org/rosbalt.ru/s/world/2021/11/23/1932327.html.

ТЮРКСОЙ — 30 лет: итоги и перспективы // https://dknews.kz/ru/politika/286994-tyurksoy-30-let-itogi-i-perspektivy

Хаджиева Г.У. Потенциал и противоречия тюркской экономической интеграции // Вестник университета Туран. 2014. № 4 (64). С. 51–56.

Чекрыжов А. Организация тюркских государств — не для всех тюркских государств // Stan Radar. 2022. 14 авг. / https://stanradar.com/news/full/50242-aleksej-chekryzhov-organizatsija-tjurkskih-gosudarstv-ne-dlja-vseh-tjurkskih-gosudarstv.html.

Чем России грозит создаваемый Анкарой «Союз тюркских государств»? // https://news.rambler.ru/troops/47113017-chem-rossii-grozit-sozdavaemyy-ankaroy-soyuz-tyurkskih-gosudarstv/?ysclid=l9lgxp73h0270309235

Чжан Юйянь. Организация тюркских государств (ОТГ): происхождение, мотивы, особенности и влияние // Вестник Пермского университета. Серия: Политология. 2023. № 1. С. 77–87.

Примечания

1 Чем России грозит создаваемый Анкарой «Союз тюркских государств»? // https://news.rambler.ru/troops/47113017-chem-rossii-grozit-sozdavaemyy-ankaroy-soyuz-tyurkskih-gosudarstv/?ysclid=l9lgxp73h0270309235

2 Турецкое агентство по сотрудничеству и координации (TİKA) // https://www.turkkon.org/en.

3 ТЮРКСОЙ – 30 лет: итоги и перспективы // https://dknews.kz/ru/politika/286994-tyurksoy-30-let-itogi-i-perspektivy.

4 Токаев ратифицировал соглашение об условиях размещения Тюркской академии в Казахстане // https://informburo-kz.turbopages.org/informburo.kz/s/novosti/tokaev-ratificiroval-soglashenie-ob-usloviyah-razmesheniya-tyurkskoj-akademii-v-kazahstane.

5 Союз тюркских университетов //https://www.turkkon.org/en/isbirligi-alanlari/education_4/turkic-university-union_14.

6 Международный фонд тюркской культуры и наследия // https://www.trend.az/tags/45715/.

7 Тюркский деловой совет // https://www.turkkon.org/en/isbirligi-alanlari/economic-cooperation_2/turkic-business-council-and-business-forums_9.

8 Тюркские страны создали новые механизмы для роста товарооборота // https://www.aa.com.tr/ru5.

9 Получится ли у Эрдогана Великий Туран? Согласна ли с этим Россия? // https://regnum.ru/news/polit/3602083.html.

10 Тюркское НАТО» станет проблемой для России и Китая // https://rosbalt-ru.turbopages.org/rosbalt.ru/s/world/2021/11/23/1932327.html.

11 Составлено с использованием данных национальных статистических ведомств и данных МВФ // https://www.imf.org/

12 Составлено с использованием данных национальных статистических ведомств и данных МВФ // https://www.imf.org/

13 Евразийская экономическая комиссия. Департамент статистики // https://eec.eaeunion.org/comission/department/dep_stat/tradestat/analytics/

14 Евразийская экономическая комиссия. Департамент статистики // https://eec.eaeunion.org/comission/department/dep_stat/tradestat/analytics/

15 Составлено авторами с использованием данных национальных статистических ведомств и данных МВФ // https://www.imf.org/

16 Составлено авторами с использованием данных национальных статистических ведомств и данных МВФ // https://www.imf.org/

17 Сайт Национального Банка Казахстана, раздел «Статистика внешнего сектора – Международная инвестиционная позиция» // https://www.nationalbank.kz/ru/news/mezhdunarodnaya-investicionnaya-poziciya

.jpg)