Capital Concentration in the Global Economy as a Factor of Unequal Distribution of Income

[Чтобы прочитать русскую версию статьи, выберите русский в языковом меню сайта.]

Mariam Voskanyan is doctor of economics, associate professor, head of the Department of Economics and Finance, Institute of Economics and Business, Russian-Armenian University (Yerevan).

SPIN-RSCI: 9605-8199

ORCID: 0000-0002-5417-6648

AuthorID: 814902

Scopus AuthorID: 57200635856

Susanna Khurshudyan is bachelor, Department of Economics and Finance, Institute of Economics and Business, Russian-Armenian University (Yerevan).

For citation: Voskanyan, Mariam and Khurshudyan, Susanna, 2023. Capital Concentration in the Global Economy as a Factor of Unequal Distribution of Income, Contemporary World Economy, Vol. 1, No 2.

Keywords: global economy, capital concentration, unequal distribution of income, Armenia.

Abstract

The problem of unequal income distribution is relevant. This article is devoted to the analysis and assessment of the level of capital concentration in the world and, as a consequence, the uneven distribution of income in the global economy, particularly in Armenia. This study shows the unevenness of capital accumulation by volume and per capita in the leading countries of the world and in post-Soviet countries. The capital accumulated in some countries makes it possible to change economic systems and ensure development on a scale that has not been seen before. Simultaneously, the unevenness of accumulation increases the gap between countries with capital and those that lack capital. Globalization exacerbates the problem of capital concentration. The concentration of capital through the creation of a global market has provided new opportunities for lagging countries to become a fully fledged part of the world's economic processes. However, in reality, the process is reversed, and the benefits of globalization accrue mainly to large owners of capital. Many countries remain outside the process of development of the global economy, and acute inequality in income distribution both within individual states and in the global arena remains an unsolved problem. The study examined in detail the theoretical background of the increasing concentration of capital in the world, highlighting the positive and negative factors of its impact on economic growth. This study also considers an example of the Armenian economy. The study concluded that capital concentration leads to unequal distribution of income globally but is also a key driver of economic growth in many countries.

1. Introduction

Unequal distribution of income and capital is one of the most pressing issues in the modern global economy. At the same time, the problem of inequality is currently based on a high degree of capital concentration and an unequal distribution of resources between capital and labor. More specifically, the unequal distribution of resources between the owners of these two factors of production (Piketty 2014).

Before the Industrial Revolution, in feudal society, wealth was mainly concentrated in the hands of large landowners, it was inherited, and the heirs of these landowners had the advantage of previously accumulated capital. People who did not have this wealth had to work for the feudal lord without even receiving a wage for their labor. As a result of the Industrial Revolution, capital accumulation shifted from landowners to the industrialists. At the same time, the wealth accumulated through capital was much greater than the wealth accumulated by landowners through the exploitation of peasant labor, i.e. the gap between the owners of capital and labor became much greater in the nineteenth century than it was before the Industrial Revolution (Sundaram, Popov 2015).

Simultaneously, the capital accumulated in individual countries served as a foundation for the industrial revolution: Countries with more capital made the transition to industrial society faster. Accumulated capital also plays an important role in the process of international capital movements. While it was initially one-way—from metropolises to colonies—it later became more stable as there was an active two-way movement of capital between countries, and even from countries themselves in need of investment. Today, the main actors in the international movement of capital are transnational corporations, whose capital flows and accumulates outside the borders of national economies.

2. Capital Concentration and Economic Development

Not surprisingly, the question of the distribution of accumulated capital in an industrial society has been a central concern of economists since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. From Thomas Malthus, for whom “overpopulation was the main problem” (Malthus 1798) of distribution and growing social and political problems, to David Ricardo, who was convinced that a small social group represented by landowners would appropriate more and more of the products of production and wealth (Ricardo 1817), to Karl Marx, who shared Ricardo’s view but saw this group as the industrial capitalists (Marx 1867), most economists tended to believe that inequality would continue to escalate and worsen. The rapidly increasing inequality caused by the growth of income from capital investment against the background of the stagnation of income from labor since the mid-19th century was the most important condition for the development of socialist movements and the spread of Marxist ideas.

Marx’s contribution to explaining the problems of capital concentration and inequality is very significant. Marx was able to foresee the changing role of different factors of production. In traditional societies, the volume of production was a direct result of the labor resources used. Marx foresaw that the role of labor would continue to lose its original importance in favor of capital, and that “the tendency of capital is to give production a scientific character and to reduce direct labor to a mere aspect of the process of production”.1 The “principle of infinite accumulation,” which is the main conclusion of Das Kapital, states that the inevitable tendency of capital to accumulate and concentrate on an infinite scale can lead either to a decrease in the rate of return on capital or to an unlimited increase in the share of capital in national income. In either case, socio-economic and political equilibrium cannot be ensured (Piketty 2014).

The shift from land ownership to industry gave rise to the massive movement of rural populations to cities, urbanisation. This led to a relative equalization of incomes between rural and urban workers (the urban workforce grew, leading to a decline in individual incomes, while the opposite was true in the villages) and a subsequent decline in inequality in income distribution. In economic theory, the relationship between inequality and per capita income is illustrated by the Kuznets curve, with Kuznets arguing in the 1950s and 1960s that social inequality increases with economic development and then decreases as a result of market forces (Kuznets 1955). In the 20th century, events such as the world wars, the Great Depression in the U.S., the Bolshevik Revolution and aggressive government policies of taxation and redistribution led to a significant reduction in inequality indicators (Piketty 2014). Workers’ wages also began to rise due to the spread of the Keynesian regulatory approach, whereby an increase in the share of labor income in national wealth would subsequently lead the recipients of that income to spend more, and thus capital income would also rise (Titenko, Korneva 2016). The share of labor income in national income grew until the middle of the twentieth century. Since the second half of the century, however, the issue has gained new momentum, mainly due to the acceleration of the globalization process and the emergence of such economic entities on the global stage as transnational corporations (TNCs). The process of international movement of capital and labor has changed. The increasing role of capital in the production process has increased the role of human capital (knowledge, skills and qualifications), which many economists believe has a direct impact on economic growth: human capital is used to make the innovations that ensure growth.

The impact of globalization on international economic processes as well as on the development and history of countries is immense. For example, the problems of individual developed countries or large corporations affect other entities beyond their borders and become global issues. The existence of strong global actors such as TNCs (or countries that are “overdeveloped” compared to the rest of the world) challenges the sovereignty of less developed countries (similar to colonies and metropolises in the early stages of capital movement), only now through a process of submission to international norms and rules in exchange for joining the global economy or integration associations.

Another trend closely related to capital concentration is the decline of the middle class, which is also the subject of research by many economists. The shrinking middle class is the result of growing income inequality and increasing concentration of capital in the hands of a small group of people (Milanovic 2016). As a result, the middle class may either reskill to further improve its social position (which is rarer) or, conversely, the quality of life of the middle class may decline. The growing concentration of capital favors the latter, and as a result increases social tensions and worsens social mobility (Piketty 2014).

For a more detailed look at the problems of inequality, let U.S. consider the forms of capitalism applied by different countries. William Baumol divides contemporary capitalism into several types (Baumol 2007):

- State capitalism, where most key economic decisions are made by the state.

- Oligarchic capitalism, where a limited number of individuals hold wealth and power.

- Entrepreneurial capitalism, where small and medium-sized enterprises play a significant role in economic development, particularly through innovation.

- Big business capitalism, where large corporations or TNCs play a significant role in economic development.

The choice of one form of capitalism or another determines the trajectory of a country’s development. These forms are not implemented in a pure state and do not exclude each other, but one of them predominates in the politics of individual countries, and it varies at different stages of development. For example, in the U.S. there is a clear predominance of entrepreneurial capitalism combined with big business capitalism (Klinov 2017), in China there is state capitalism combined with big business capitalism, and in more underdeveloped countries and many post-Soviet states oligarchic capitalism dominates.

These forms determine, among other things, the extent of the problem of inequality and high concentration of capital in a country, as well as the extent to which countries’ policies prioritize development and growth. In countries with an oligarchic form of capitalism, the problem of income and wealth distribution is exacerbated because the development of the country is often not the main goal of government policy, which is instead aimed at preserving and increasing the power and wealth of the oligarchs. In such countries, according to William Baumol, “revolution may be the most effective (and perhaps the only) means of abolishing oligarchic capitalism and moving to a system in which growth becomes the primary goal of government” (Baumol 2007).

In the early stages of development in capitalist countries, this form of capitalism prevailed as the accumulation of capital in the hands of individuals served as an important engine of economic growth. Later, as the economy developed, the role of the state became increasingly important (as can be seen in the example of catching-up countries, where in the early stages the role of the state in regulating the market and creating institutions to ensure growth was indispensable). As institutions develop in a country, state capitalism loses its initial role and the role of another type of capitalism—big business—increases. The state does not lose its role in the distribution of income and wealth, but the way in which it intervenes changes. For example, as noted above, state intervention in economic and political processes in the twentieth century led to a reduction in income inequality. Today, state capitalism also reduces the gap between different segments of society.

Tom Piketty has shown that social inequality in the U.S. and Europe has been on the rise again since around the 1970s. Thus, a certain improvement between the world wars and in the first decades after the Second World War has been replaced by a reversal, putting science and economic policy in a challenging situation (Pikkety 2014).

Globalization has led to an increasing role for big business capitalism, and this form is currently dominant in developed market economies. In some developed countries, a slow transition to entrepreneurial capitalism is taking place.

The growing role of big business capitalism has led, among other things, to a greater concentration of capital in the hands of TNCs. As noted above, these companies are beyond the control of governments, which complicates the application of state regulatory measures. On the one hand, TNCs have enough money to invest in research and development and to develop the economy of one country or another. On the other hand, many TNCs have no interest in doing so, since their market power gives them long-term competitive advantages, leading to even greater concentration of capital without further redistribution. Thus, as TNCs have become more capitalised, income inequality has increased again and the gap between developed and developing countries has widened.

Globalization and the increasing role of large corporations in some countries have also made resources more mobile. For example, productive resources, especially raw materials, move from developing countries to developed countries through TNCs, which, because of their accumulated capital, can (according to economic theory) make better use of these resources and subsequently concentrate even more resources in their own countries.

Countries that export these raw materials, in turn, experience capital outflow, as the TNCs, and not the countries that originally owned these resources, receive the capital income. The latter are only interested in exploiting the resources of these countries, not in developing them, which means that the developed countries, represented by the TNCs, benefit from globalization because they have new opportunities to control resources. Of course, TNCs also benefit the host country by contributing in some way to its development. However, there is a disproportion between the level of development of these countries and the tendency for capital to be concentrated in TNCs as a result of the use of cheap production resources. Development is taking place at a much slower pace than the trend of capital outflow and concentration. Thus, on balance, the developing countries that host these corporations lose out.

The movement of capital from developing to developed countries leads to its concentration in the latter, giving these countries political and economic power. For example, the vast majority of TNCs are currently American, which has become one of the reasons for global unipolarity. Globalization has led to the formation of a world order in which international organisations no longer act on the basis of international law, but rather formalise the power politics of the leading countries through their decisions (Rybalkin, Shcherbanin, Baldin et al. 2003).

The movement towards entrepreneurial capitalism could become a new driver of global development. According to many studies, small and medium-sized enterprises are more important than large companies in the creation of new technologies and are the carriers of innovation and development (Schumpeter 1934). Such firms do not have sufficient capital to invest in research and development, while large firms are not motivated to do so. The further development of entrepreneurial capitalism may lead to increased competition and less concentration of capital in the hands of a limited number of firms and thus to a reduction in income inequality. At present, however, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- Concentration of wealth (capital) is observed at different stages of development of economic systems, but the ways of capital accumulation change with the course of their development.

- The process of concentration and accumulation of sufficient capital was the main prerequisite for the industrial revolution.

- The concentration of capital at that time was the cause of rapid economic growth, especially in countries where this concentration was higher (e.g., England).

- The concentration of capital was also accompanied by an unequal distribution of income, which in turn led to social injustice and high levels of poverty in some countries.

3. Capital Concentration in the Global Economy: Major Trends

Accumulated wealth plays an important role in economic development, so let U.S. look at how the world’s wealth is distributed among countries. In this respect, it is interesting to analyse the data on capital concentration by country, first of all in terms of their share of world capital, as well as the dynamics of changes in this share over the last few decades.

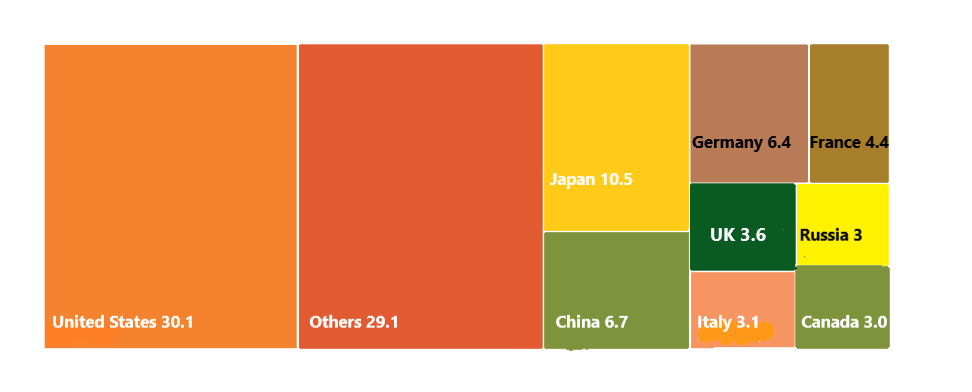

As we can see in Figure 1, in 1995 the United States was in first place in terms of its share in world capital formation. And this share was larger than that of the rest of the world excluding the top 10 countries. Japan came second (10.5%), followed by China (6.7%), Germany (6.4%), France (4.4%), the United Kingdom (3.6%), Italy (3.1%), Russia (3%), and Canada (3%).

Figure 1. Top 10 countries in terms of capital formation, in % of global capital formation, 1995

Source: World Bank database - https://databank.worldbank.org/

The capital concentration pattern changes if we consider this indicator on a per capita basis (see Fig. 2). In this case, the U.S. still ranks first in the top ten, but China is already ninth in the top ten in terms of total capital accumulated in 1995 (about 4.9% of the U.S. figure). At the same time, the rest of the population accounts for a negligible amount (about 4.5 % of the U.S. figure).

Figure 2. Accumulated capital per capita in the top 10 countries in terms of accumulated capital, in thousands of U.S. dollars, 1995

Source: World Bank database - https://databank.worldbank.org/

The concentration of capital in the world has changed significantly by 2018 (see Figure 3). Although the United States is still the world’s leading economy, its share has fallen to 24.7%, while China has tripled its share to 21.1%. At the same time, the top ten countries have reduced their share of total world capital. Another important change is the addition of Brazil to the list. As in many other cases, developing countries are rapidly assuming dominant positions on the world stage. China is now leading this process, but other emerging economies are significantly strengthening their position in terms of gross capital formation, not to mention their success in terms of economic growth and share of global GDP. A good example is India, where the share of gross capital formation has grown 3.7 times since 1995, well above the world average of 1.65 times.

Figure 3. Top 10 countries in terms of capital formation, in % of global capital formation, 2018

Source: World Bank database - https://databank.worldbank.org/

It should be noted that the distribution of per capita wealth in 2018 differs significantly compared to 1995 (see Figure 4). Although the U.S. has consistently ranked in the top ten, China’s figure has increased significantly and reached 18.8 % of the U.S. level, while the rest of the countries’ figures are 5.5 % of the U.S. level.

Figure. 4. Accumulated capital per capita in the top 10 countries in terms of accumulated capital, in thousands of U.S. dollars, 2018

Source: World Bank database - https://databank.worldbank.org/

As noted in Section 1, the accumulation of capital within a country has historically meant that it is better placed to embark on a path of development than countries that do not possess this capital. Sufficient capital accumulation in England led to a much faster industrial revolution than in the rest of the world; Japan, thanks to its accumulated capital, was able to rebuild its economy in a very short time after the war and become an advanced technological nation, etc. China’s economic development strategy in recent decades has also been based on accumulating wealth at a faster rate than consumption growth. As of 2018, China is the world’s second largest economy in terms of accumulated capital, just behind the US. Therefore, it is safe to say that wealth accumulation is one of the most important drivers of endogenous growth.

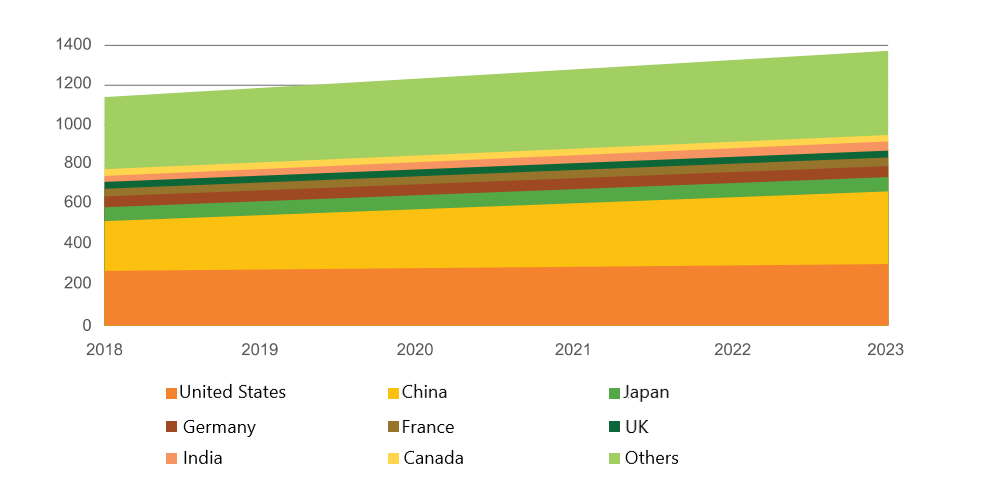

Turning to trends in accumulated capital, it is worth noting that, despite the leading position of developed countries, the rate of capital accumulation is significantly higher in developing countries (see Figure 5). The average annual growth rate of accumulated capital in the world between 1995 and 2018 was 2.9 %; for the U.S. it was 2 %, for China 8.1 % and for India 5.7 %.

Data on accumulated capital after 2018 are not available. Assuming that the average growth rate for these countries is maintained until 2023, China is expected to lead with 26% of the world’s accumulated wealth; the U.S. follows in second place with 22.7% of the world’s wealth; third and fourth places are held by Japan and Germany with 5.25% and 4.37%, respectively; and India moves into fifth place, overtaking France and the UK, with 3.12% of the world’s wealth (Table 1, Figure 5).

Figure 5. Structure of global capital formation in 2018-2023, in trillion dollars, estimated by the average annual growth rate for each country over the period 1995-2018

Source: World Bank database - https://databank.worldbank.org/

Of course, the situation may have changed as a result of the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, as there was a jump in market capitalisation and, consequently, concentration of capital in the leading TNCs (most of which are American), and therefore these results may deviate from reality. Nevertheless, disregarding the pandemic, the following picture should have emerged in 2023 (Table 1).

Table 1: Top 20 countries by accumulated capital in 1995, 2018, 2023 (forecast), share in global capital accumulation

|

Country |

1995 |

Global rank |

2018 |

Global rank |

2023* |

Global rank |

|

United States |

30.10% |

1 |

24.74% |

1 |

22.76% |

2 |

|

China |

6.69% |

3 |

21.08% |

2 |

26.00% |

1 |

|

Japan |

10.52% |

2 |

6.14% |

3 |

5.25% |

3 |

|

Germany |

6.45% |

4 |

4.84% |

4 |

4.37% |

4 |

|

France |

4.44% |

5 |

3.29% |

5 |

2.96% |

6 |

|

United Kingdom |

3.63% |

6 |

2.85% |

6 |

2.60% |

7 |

|

India |

1.50% |

13 |

2.83% |

7 |

3.12% |

5 |

|

Canada |

2.95% |

9 |

2.65% |

8 |

2.48% |

8 |

|

Russia |

2.99% |

8 |

2.17% |

9 |

1.95% |

10 |

|

Brazil |

2.53% |

10 |

2.13% |

10 |

1.97% |

9 |

|

Italy |

3.15% |

7 |

1.97% |

11 |

1.71% |

12 |

|

Australia |

1.58% |

12 |

1.79% |

12 |

1.77% |

11 |

|

South Korea |

1.12% |

17 |

1.60% |

13 |

1.66% |

13 |

|

Spain |

1.83% |

11 |

1.33% |

14 |

1.20% |

14 |

|

Indonesia |

0.92% |

19 |

1.12% |

15 |

1.13% |

15 |

|

Mexico |

1.20% |

16 |

1.08% |

16 |

1.02% |

16 |

|

Netherlands |

1.26% |

14 |

1.03% |

17 |

0.95% |

17 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

1.00% |

18 |

0.95% |

18 |

0.90% |

18 |

|

Switzerland |

1.24% |

15 |

0.95% |

19 |

0.86% |

19 |

|

Sweden |

0.76% |

20 |

0.66% |

20 |

0.62% |

20 |

Source: World Bank database - https://databank.worldbank.org/

*-data for 2023 is calculated based on average annual growth rate

4. Structure of Accumulated Capital

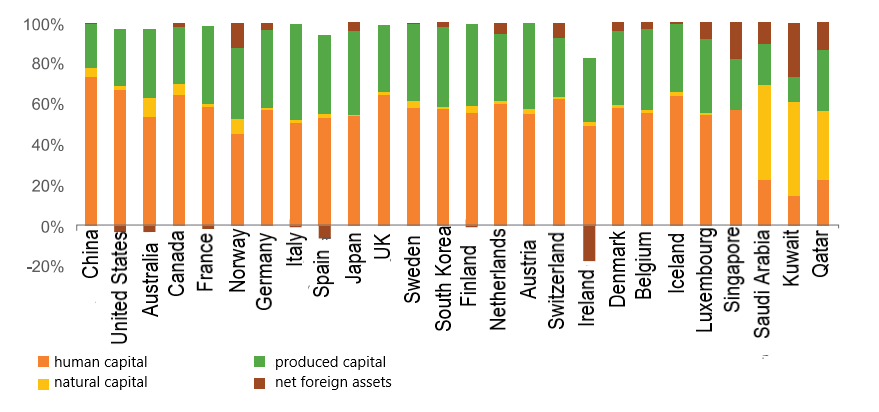

The accumulated capital or total wealth of a country consists of four components: human capital, natural capital, produced capital, and net foreign assets. Of course, each of these components is important in the development path, but the way in which this wealth is used for development purposes and the proportions in which these components make up total wealth determine a country’s level of development. Figure 6 shows the components of total wealth for developed countries. China and the United States are the leaders in terms of absolute natural capital, but natural capital represents only a small fraction of total wealth (4% for China and 2% for the United States). Saudi Arabia ranks third in terms of natural capital, but it accounts for 46.6% of total wealth in the country. For Iraq, the share of natural capital is 66%, for the UAE 26.9%, for Kuwait 46%, and for Qatar 39.9%. Compared to the U.S. and China, the other components of wealth are less developed in these countries. For the leading countries shown in Figure 6 (excluding Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Qatar), the average ratio of wealth components is as follows:

- Human capital: 59.7 %.

- Natural capital: 2.4%.

- Produced capital: 36.7%.

- Net foreign assets: 1.3%.

Figure 6. Components of wealth in the world’s leading countries, 2018

Source: World Bank database - https://databank.worldbank.org/

Thus, the main component of wealth in these countries is human capital. Net foreign assets in most developed countries are positive, i.e., entities in these countries own more foreign assets than foreign entities do in those countries. Thus, capital outflows from these countries are greater than inflows.

In China, the average value of the shares of wealth components in total wealth is as follows:

- Human capital: 73.3%.

- Natural capital: 3.9%.

- Produced capital: 22%.

- Net foreign assets: 0.08%.

This suggests that China has made an economic leap based on the growth of human capital. The lack of large mineral resources is not an obstacle to growth, but it does require more sophisticated development policies, which is clearly reflected in the level of accumulated capital of different countries. At the same time, the capital gap between China and the United States remains.

The international movement of capital, and more generally the essence of a capital-based market economy, implies that capital should flow from developed countries (or countries where there is a surplus of this capital) to countries where there is a shortage of capital (and consequently the return on capital is higher), i.e., developing and underdeveloped countries.

Let U.S. look at the components of wealth and the countries at the bottom of the list in terms of total wealth and the components of their national wealth (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Wealth components of least developed countries, 2018

Source: World Bank database - https://databank.worldbank.org/

The difference in the ratio of components is striking. At first glance, some of these countries may appear to have developed human capital, as its share in total wealth is relatively high; however, in absolute terms, the amount of human capital is very small. Most of these countries are traditional economies, so the share of natural capital in total wealth is relatively high and manufactured capital plays a small role. The share of net foreign assets is expressed in negative values, i.e., in this case capital inflows from the remaining countries exceed capital outflows from these countries. In general, the average value of the component shares for the selected countries is as follows:

- Human capital: 52.6%.

- Natural capital: 32.2%.

- Produced capital: 20.4%.

- Net foreign assets: -5.2 %.

Looking at the general trends of the above groups of countries, it can be observed that capital flows from developed to developing countries and that the main asset of developed countries compared to developing countries is human capital. The development of human capital can be a good development opportunity for countries that do not have natural capital.

5. Factors of Capital Concentration in Developing Countries: The Case of Armenia

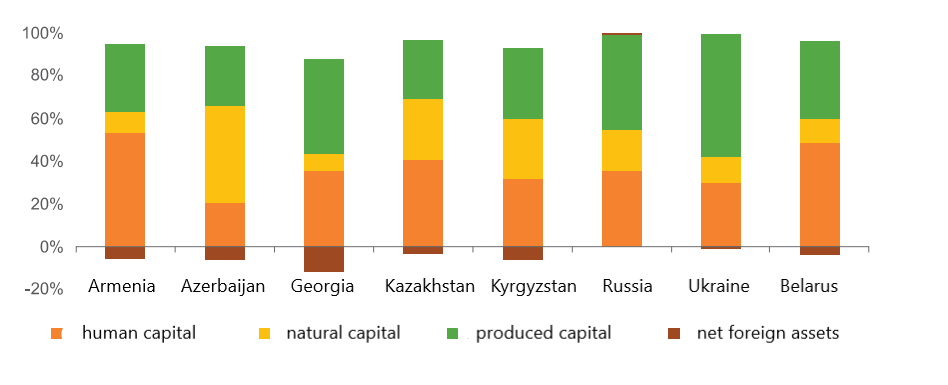

Among the developing countries, consider the post-Soviet countries and their wealth components (see Figure 8).

Compared to the least developed countries, the share of productive capital is higher in these countries, and natural capital also plays a significant role. The average shares of capital components in the post-Soviet countries are as follows:

- Human capital: 41%.

- Natural capital: 22.4%.

- Produced capital: 42.4%.

- Net foreign assets: -5.8%.

Figure 8. Wealth components of post-Soviet countries, 2018

Source: World Bank database - https://databank.worldbank.org/

In all countries except Russia, foreign companies own more assets in the country than domestic companies own abroad.

It is also important to note that, in most cases, natural capital dominates in extractive economies. On the other hand, in Russia, for example, production capital dominates, despite the huge role of the commodity segment in the country’s economy.

Table 2 presents the indicators shown in Figure 8 in dollar terms.

Table 2: Post-Soviet countries and components of their wealth per capita, in U.S. dollars, 2018

|

|

human capital |

natural capital |

produced capital |

net foreign assets |

|

Armenia |

30547.51 |

5493.624 |

18326.2 |

-3376.67 |

|

Azerbaijan |

8173.801 |

18832.27 |

11209.88 |

-2740.16 |

|

Georgia |

18142.14 |

3920.116 |

22775.96 |

-6182.68 |

|

Kazakhstan |

44364.47 |

30528.82 |

30536.5 |

-3835.04 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

5151.707 |

4634.579 |

5588.752 |

-1129.89 |

|

Russia |

61473.2 |

32965.4 |

78047.35 |

2021.891 |

|

Ukraine |

19644.14 |

7650.702 |

38217.22 |

-607.027 |

|

Belarus |

42015.97 |

9787.67 |

31693.59 |

-3668.02 |

Source: World Bank database - https://databank.worldbank.org/

As far as Armenia is concerned, the structure of accumulated capital is such that human and production capital predominate, which are the country’s competitive advantages.

Figure 9. Distribution of income in Armenia

Source: World Inequality Database - https://wid.world/

There is a direct correlation between the ratio of wealth components and inequality: the growth of the Armenian economy leads to an increase in the gap between the top 1% of the population and the bottom 50%. The development of productive capacities, human capital, GDP per capita, etc. does not increase the income of the majority of the population (there is a correlation, but it is too weak). They mainly benefit big business, not the economy as a whole. The situation is the same in Russia and other post-Soviet countries with oligarchic capitalism: all the country’s major capital-intensive industries are concentrated in the hands of a small group of people. The Gini coefficient for income distribution in Armenia (0.57–0.58) is really high (Figure 9), significantly higher than not only in Europe but also in China and Russia. The values of the Gini coefficient for wealth distribution are also extremely high (0.83–0.84).

Figure 10. Distribution of wealth in Armenia

Source: World Inequality Database - https://wid.world/

In China and the U.S., there is a direct correlation between income inequality and economic growth, i.e., inequality increases as growth drivers develop. In Armenia and other post-Soviet countries, the opposite is true. This is good from the point of view of equity, but on the other hand, it means that in these countries, human capital does not determine the trend of income growth, and the income gap between high-skilled and low-skilled labor increases very slowly, while responding poorly to external conditions.

Indeed, the example of the Armenian economy shows that excessive concentration of capital is an obstacle to development. For Armenia, the situation is complicated by an underdeveloped capital market, with key industries in the hands of a limited number of people. The widening wealth gap between the top 1% and the bottom 50% of the population can only have a negative impact on the development of the Armenian economy and the country as a whole.

As mentioned above, the income of the bottom 50% does not correlate with the Gini coefficient, neither in terms of income nor in terms of wealth, and the general trend of this indicator is determined by the income and wealth trends of the top 1% of the population (while the trend of the top 10% moves in the same direction as the trend of the top 1%).

Thus, the high level of income inequality in Armenia, expressed as the ratio of the income of the top 1% of the population to that of the bottom 50%, can be seen as the result of the initial unequal distribution of capital, for example, private property as a result of ineffective privatization.

6. Main Conclusions

To summarise the research carried out, it can be said that in traditional societies, the volume of output depends mainly on labor productivity, as the economy is dominated by labor-intensive industries that are by and large dependent on a single factor of production, labor. This can be seen in our selected African countries, where capital concentration and level of development are not correlated, and improvements/declines in development indicators have little impact on labor income.

In developed countries, however, the role of labor resources is diminishing in favor of capital resources, with the result that the recipients of labor income, especially low-skilled workers who make up the middle class, either have to increase their human capital and move up the ladder or, conversely, move down the ladder in terms of income and wealth. In this way, the middle class shrinks and the concentration of capital increases.

Unfortunately, the fact that income and wealth are not correlated means that in most cases the wealth of the richest families is passed down from generation to generation, and the heirs of the richest families only add to the wealth accumulated before them. Since, due to economies of scale, capital gains are faster for already concentrated capital, there is little scope for social mobility for the rest of the population, and even if there is, the leap is not very high. Therefore, a person who does not own generational wealth cannot claim the level of wealth of the heirs of the richest families during their lifetime. This trend is set to increase as capital becomes more concentrated.

Of particular interest are the post-Soviet countries with an oligarchic form of capitalism. In these countries, including Armenia, incomes are almost unresponsive to economic conditions, and improvements in economic performance lead to a divide between social strata, as the sectors that underpin economic growth are controlled by a limited number of individuals and benefit only them.

Thus, the general conclusion can be seen as the thesis that concentration of capital, if properly directed, can lead to rapid growth and development of a country, but excessive concentration, on the contrary, begins to widen the gap between the income and wealth of the population. For capital-deficit countries like Armenia, it is crucial to channel capital properly to develop the sectors of the economy, which requires systematic action by the government.

Capital accumulation allowed China to become a new economic center of the world alongside the U.S. in a few decades, so its role in the country’s development cannot be ignored. Although Armenia’s capabilities cannot be compared to those of China, with the right policy of using the accumulated and reproducible human and physical capital, it is possible to embark on the path of long-term and dynamic development.

Bibliography

Baumol, W. J., Litan, R. E., Schramm, C. J., 2007. Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism, and the Economics of Growth and Prosperity. Yale University Press.

Belykh, A.A., Mau, V.A, 2018. Marx-XX. Voprosy ekonomiki, No 8, p. 78.

Klinov, V., 2017. Sdvigi v mirovoy ekonomike v XXI veke: problemy i perspektivy razvitiya [Shifts in the world economy in the XXI century: problems and prospects of development]. Voprosy ekonomiki, No 7.

Kuznets, S., 1955. Economic Growth and Income Inequality. The American Economic Review, Vol. 45, No 1.

Malthus, Th., 1798. An Essay on the Principle of Population.

Marx, K., 1867. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. 1. Part 1: The Process of Capitalist Production. New York, NY: Cosimo.

Milanovic, B., 2016. Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization. Harvard University Press.

Piketty, Th., 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Ricardo, D., 1817. On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.

Rybalkin, V.E., Shcherbanin, Y.A., Baldin, L.V. et al., 2003. Mezhdunarodnyye ekonomicheskiye otnosheniya: ucheb. [International economic relations: textbook]. 4th edition. Moscow: Unity.

Schumpeter, J. A., 1934. The Theory of Economic Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Economic Studies.

Sundaram, J.K., Popov V., 2015. Income inequalities in perspective. Initiative for Policy Dialogue–Geneva ILO, 2015. Extension of Social Security Series. No 46. International Labor Office, Social Protection Department.

Titenko, E., Korneva, O., 2016. The Concentration of Capital as a Reason for the Accelerated Development of the Economic System in: Lifelong Wellbeing in the World – WELLSO 2015 / F. Casati (ed.). Future Academy.

Notes

1 Cited from: Belykh, Mau 2018.

1.jpg)