The NDB and SDGs: Does the Bank Fulfill Its Mandate?

[Чтобы прочитать русскую версию статьи, выберите русский в языковом меню сайта.]

"As an innovative institution, NDB has to permanently be up to the challenge of being always new."

Marcos Troyjo, President of the New Development Bank

Alexandra Morozkina is deputy dean of science at the Faculty of World Economy and International Affairs, HSE University, and senior research fellow at the Financial Research Institute of the Ministry of Finance of the Russian Federation.

SPIN-RSCI: 9712-7730

ORCID: 0000-0002-9529-9601

ResearcherID: I-4257-2016

Leonid Grigoryev is academic supervisor and tenured professor at the School of World Economy, HSE University.

SPIN-RSCI: 8683-3549

ORCID: 0000-0003-3891-7060

ResearcherID: K-5517-2014

Scopus AuthorID: 56471831500

For citation: Morozkina, Alexandra and Grigoryev, Leonid, 2023. The NDB and SDGs: Does the Bank Fulfill Its Mandate? Contemporary World Economy, Vol. 1, No 3.

Keywords: NDB, SDGs, Multilateral Development Banks, financing for development, SDG reporting, inequality

Abstract

Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) have long played an important role in resolving of international challenges, including though research cooperation. They are believed to be less politically engaged than bilateral development assistance programs and therefore better positioned to form the global agenda. The New Development Bank (NDB), in its turn, is an especially important player among MDBs, since it is one of the few institutions with the world’s largest economies as its co-founders, but without any of the G7 economies. In 2020 it showed its ability to provide well-timed and effective loans to its members during crises, approving the first NDB Emergency Assistance Program in Combating COVID-19 in March 2020.

In this article we discuss changes to the global sustainable development agenda and the NDB’s contribution to the sustainable development goals (SDGs) in member countries, potential instruments and priority sectors in the longer-term and implications for the global financial architecture, given the changing global economic environment. We have looked at the alignment of NDB projects with the SDGs and concluded that the NDB primarily contributes to SDG 6, SDG 7, SDG 8, and SDG 9, with the latter – with its 49 projects – leading the way. This is consistent with the Bank’s mandate, which highlights infrastructure as a primary sector of investment.

Introduction

The shocks of the last years severely disrupted global sustainable development plans and require a serious reconsideration of the 2030 agenda. One of the main outcomes of this crisis is increased inequality, within and between countries. As developed countries have been focusing on their own paths out of recession, and their domestic fiscal stimuli have increased on an unprecedented scale, their assistance to developing countries in need was far more modest.

Total official development assistance (ODA) from the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) countries increased by 11% [OECD, n.d.] to USD 206 billion in 2022. However, the scope and complexity of global needs have increased dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic: as per OECD estimates, the SDG financing gap increased up to USD 3.7 trillion in 2020 [OECD 2021a. P. 15]. Both these trends - a small increase in assistance and a large increase in development financing needs - have led to a decline in the relative capacity of the ODA. The situation looks especially unfair when one looks at the geographical distribution of assistance: the share of low-income countries as recipients fell by 3.5 per cent to USD 25 billion in 2020 in comparison to 2019 [OECD 2021a. P. 8]. As one might expect, the ODA’s priorities had shifted to healthcare and medical needs (especially vaccination) during the pandemic [IHME 2021].

Disruption of the SDGs and a relative decrease in financing has led to a change in the type of challenges faced by international society, from short-term analysis and measures to deeper layers of problems in terms of adaptation to current and possible future crises and the long-term development agenda. The same applies to development cooperation: the key issue is how to provide support for a number of small countries that have been affected, or less developed countries with significant losses in income. But in the longer term, the key problem is the restoration of growth and a return to the path of development, as well as resolving issues pertaining to adaptation to crises. Regional or systemic banks are expected to follow the deep changes in the global agenda.

The bilateral and multilateral assistance agenda has been shifting in recent years. The 2020 pandemic took the world aback, and all countries had to find their own ways to fight the disease with limited international assistance, rather than it being united international effort. The global agenda started to include more healthcare issues, “new poverty”, etc. [Grigoryev, Morozkina 2022]. At the same time, the issue of energy security started to grow in importance [Grigoryev, Medzhidova 2020]. In 2020-2022, global political and economic processes started running ahead of the capability of response of the multilaterals and national governments. The recovery of 2021 came at the same time as the early commodity cycle and was characterized by a delayed recovery in services, but fast growth in consumer demand. Energy and commodity prices have been growing much faster than consumer inflation in general, and there was a danger of stagflation from the 1980s returning. Before any remedies were found and employed, Russia’s special military operation (which began on 24 February 2022) received a dramatic response in the shape of sanctions from NATO and the EU countries. It is probably fair to say that the traditional development agenda, global governance, and the path of global economic growth may never be the same as in previous decades.

In these difficult circumstances, multilateral development banks, as both research institutions and participants in the system of development assistance, have to play a decisive role in shaping the new framework. They are believed to be less politically engaged [Morozkina 2019] and thus have a more balanced position in terms of global development and its financing.

This article considers the potential role of the multilateral development banks (MDBs) and the New Development Bank (NDB) in particular in updating the sustainable development agenda globally. In the first section, the most recent trends in sustainable development framework and long-term implications are analyzed, while in the second section, the theoretical role of MDBs in sustainable development are examined. In the third part, the data sources and evaluation methodology of the NDB’s role in sustainable development are explained. In the fourth section we look at the activities of the NDB in the field of sustainable development, and in the final section we give some recommendations on the development of NDB policies.

Latest trends in SDGs

The shock of the COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted global sustainable development plans in 2020-2022 and affected all the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Until 2019, the international community appeared optimistic about the then course of events (based on the UN National Voluntary SDG reports). Discussions relating to the achievement of the SDGs commonly focused on the expected success of the implementation of the SDG agenda by 2030, although, at the same time, achievements on the ground were not impressive in many respects. The recent Global Sustainable Development Report shows pathways for critical transformations needed to accelerate global efforts in terms of development [UN 2023]. The shock caused by the COVID-19 pandemic changed the anticipated early trajectory, disrupted the SDGs, and created a new list of problems to address. For example, the year 2020 demonstrated the unsustainability of some of the results that had been achieved thus far [Sachs et al 2021]. Further, the global average index measuring the performance of countries in terms of the SDGs declined in 2020 for the first time since 2015, and the pandemic and following shocks have already severely affected the first goal (SDG 1, End poverty in all its forms everywhere) as the number of the people living on less than USD 1.90 per day has increased by more than 75-95 million people, while at the same time their proportion of the world population grew from 8.7% in 2019 to 9.6% in 2020 [World Bank n.d.]. Other goals were surely also severely affected, as is shown by the UN [UN 2023]. The proportion of undernourished people increased from 8% in 2019 to 9.8% in 2021 [UN 2023. P. 10]. SDG 3 (Good health and well-being) seems to be no longer achievable with the decline in life expectancy during 2020 in most European countries [EC 2021]. Target 3.3, “By 2030, end… epidemics… and other communicable diseases” appears to be inconsistent with present realities [UN 2015], especially given the growing number of COVID-19 deaths from 1.8 million in 2020 to 4.8 million in 2021 [Our World in Data n.d.].

SDG 4 (Quality education) will also require correcting given the mass school closures in 2020 and the effects on education, which are yet to become clear. For example, in April 2020, schools in 173 countries were closed due to lockdowns, and in 7 more countries schools were kept only partially open [UNESCO 2021]. Given the differences in access to digital education, school closures also increased inequality within and between countries depending on access to online education during lockdowns (Goal 10, Reduced inequalities).

In addition to the above, SDG 8 (Decent work and economic growth) showed a negative performance with rising global unemployment, up from 5.4% in 2019 to 5.8% in 2022 [UN 2023. P. 14].

SDG 7 (Affordable and clean energy) and SDG 13 (Climate action) were, at first, seen as having gained from the lockdowns. But they did not fare better than the other SDGs in the end, with daily CO2 emissions eventually increasing and overcoming pre-crisis levels no later than the beginning of 2021, and in sum being much higher than expected. Total CO2 emissions in 2020 were only 5.4% lower than in 2019 [Liu et al. 2021]; GHG emissions in 2021 had surpassed the 2019 level not only in China, but in many other countries, and globally. Coal returned in 2021, even in EU countries. That was a negative signal for the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow in November 2021, which was to set new, advanced goals on the climate agenda. There is no shortage of energy globally and, for the most part, regionally.

While high prices for traded energy materials reached new heights at the beginning of 2022, sanctions, and later, the partial embargo for Russia energy exports (also metals and fertilizers) brought the prices to even higher, and rigid, levels. The same should be said about grain prices, dependent also on energy and transportation costs, which in turn depend on policies for cargo shipping and the use of ports. In terms of strategic planning in the development context, we can highlight the key three current challenges: (1) the challenging situation during 2022; (2) the long-term limitation on financing, logistics and management on the SDG agenda; (3) the change of priorities in the long run for many governments and multilaterals.

The overall effect of the 2020 crisis has been described as “catastrophic” [UN 2021]. It has increased the financing gap for developing countries to overcome the crisis and also to achieve the SDGs by at least 50%, amounting to USD 3.7 trillion in 2020 [OECD 2021a]. The IMF has also voiced concerns regarding the vaccination gap [IMF 2021. P. 2-3].

Given the potential for present conditions to become endemic, and ultimately creating a ‘new normal’, scholars such as Bobylev and Grigoryev (2020), Grigoryev and Medzhidova, (2020), and Grigoryev et al, (2021) have proposed some amendments to the SDGs. They suggest that it is necessary to strengthen the concept of the value of human life in the SDGs and propose two options: first, transforming SDG 3 (Good health and well-being) to include health-related indicators from other SDGs, e.g. redistributive impact of fiscal policies (target 10.4), which, among other things, means access to healthcare facilities; second, creating an additional SDG in light of the concept of the value of human life and the risk of epidemics and new diseases [Bobylev and Grigoryev 2020].

For a long time, the differences between national healthcare systems reflected the institutional settings of societies and taxation systems. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, it is concerning that despite the uneven performance of healthcare systems in developed countries (and we are not talking about developing countries here) at the time of the pandemic, there have been no public calls for reviewing the above-mentioned financial and institutional healthcare framework in the new environment. Of course, it is hard to launch this kind of overhaul in the midst of an ongoing crisis. But the absence of debate on creating more adequate systems in the future looks puzzling, though it is understandable from the viewpoint of vested interests in the existing healthcare systems: the state (state budgets); private financing; companies providing medical drugs, etc. From this viewpoint, and as seen in Table 1 below, there are more questions than answers. Huge differences in healthcare expenditures per capita among the global community have protected people from COVID-19 infections. All countries and medical organizations were doing their best to combat the pandemic, while social and financial problems now look deeper than just managerial and budgeting issues. Unexpectedly, the US and UK also have relatively high rates of deaths during these two years, which are close to the COVID-19 mortality rates reported in Brazil and Mexico. Such correlations are worthy of a call for a review of traditional views on healthcare systems as they relate to the SDGs. At the same time, such adverse results partly explain the difference between the scale of domestic and international reactions of donor countries, as advanced economies struggled with their own difficulties. Multilateral development institutions may play a significant role in such discussions of the ways to increase the sustainability and resilience of social systems, given their expertise and more neutral role.

Table 1. Differences in healthcare systems, latest available data* (2020 for expenditures and March 2022 for the COVID-19 effect)

|

|

Healthcare expenditures, current USD per capita, 2020 |

Cumulative number of COVID-19 deaths, % of population |

Cumulative number of confirmed COVID-19 cases, % of population |

Share of people fully vaccinated, % of population, March 2022 |

|

High-income countries, incl. |

6,176 |

0.19 |

22.3 |

74 |

|

US |

11,702 |

0.30 |

24.3 |

66 |

|

UK |

4,927 |

0.25 |

31.5 |

72 |

|

France |

4,492 |

0.21 |

37.8 |

78 |

|

Germany |

5,930 |

0.16 |

25.4 |

75 |

|

Upper-middle-income countries, incl. |

527 |

0.10 |

4.9 |

76 |

|

Russia |

774 |

0.25 |

12.2 |

50 |

|

China |

583 |

0.00 |

0.0 |

86 |

|

Mexico |

539 |

0.25 |

4.4 |

61 |

|

Brazil |

701 |

0.31 |

14.1 |

75 |

|

South Africa |

490 |

0.17 |

6.3 |

30 |

|

Lower-middle-income countries, incl. |

95 |

0.04 |

2.7 |

50 |

|

India |

57 |

0.04 |

3.1 |

60 |

|

Ukraine |

270 |

0.25 |

11.4 |

35 |

|

Philippines |

165 |

0.05 |

3.4 |

59 |

|

Low-income countries, incl. |

34 |

0.01 |

0.3 |

11 |

|

Ethiopia |

29 |

0.01 |

0.4 |

18 |

* All countries in the World Bank database by income groups (and averages)

Source: World Bank (n.d.), Our World in Data (n.d.)

MDBs in sustainable development

The role of multilateral development banks in sustainable development agenda has long been recognized by scholars. There are four key groups of MDB activities in relation to sustainable development recognized by researchers: increase of financing for development; incorporating SDGs in operational process (project requirements and evaluation); promotion of the agenda and norm setting; the mobilization effect on private financing.

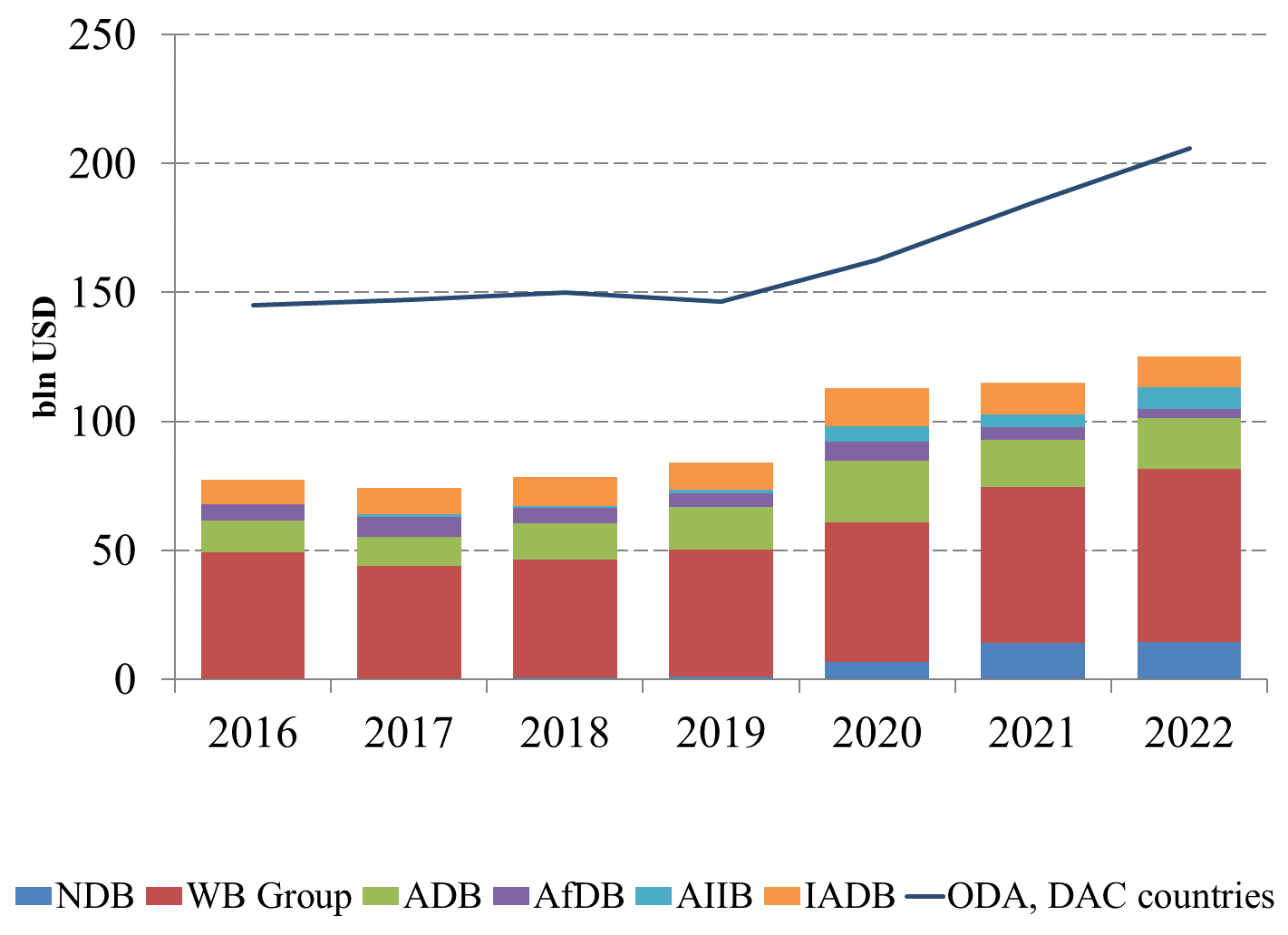

Although sometimes MDBs are seen as marginal sources of financing for development in comparison to bilateral financing [Kenny 2019], generally, international society sees them as an important source of development financing [Avellan et al. 2022; Griffith-Jones 2016]. The role of development banks is particularly important in crises, when multilateral finance usually plays a more counter-cyclical role [Griffith-Jones 2016, Griffith-Jones and Gottschalk 2012] than bilateral financial flows. This phenomenon was once more justified in 2020, when six key MDBs (the World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB), African Development Bank (AfDB), Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB), NDB) quickly stepped in with a large increase in disbursements. Their collective disbursements increased by 34% in 2020, whereas ODA bilateral disbursement by the Development Assistance Committee rose by only 10% during the same period (Figure 1). For example, the high rating and access to finance allowed the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, part of the World Bank Group) to raise USD 15 billion through sustainable development bonds over a three-day period [World Bank 2021]. Of course, in absolute terms, bilateral ODA from DAC countries is by no means comparable to total disbursements of MDBs, because not all of the latter flows are counted as ODA.

Figure 1. Disbursements of the key MDBs and ODA of Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Countries, 2016-2022, bln USD

Source: World Bank (2023), NDB (2023), ADB (2023), AfDB (2023), IADB (2023), AIIB (2023), OECD (n.d.)

The second way to support sustainable development is to align the operations of the bank with it. Günther Handl concludes that multilateral development banks have the ability and “international legal obligation to take sustainable development considerations into account” [Handl 1998. P. 665]. For example, the New Development Bank publishes its contribution to the SDGs in its annual report [NDB 2021] and takes the sustainability of a project into consideration as one of the criteria for approval [NDB 2022]. MDBs also use innovative financial instruments and play a role in scaling them. Mendez and Houghton (2020) highlight the role of MDBs in promotion of green bonds and emphasize that “MDBs (and other supranational agencies) were green bonds’ only issuer before 2012” [Mendez, Houghton 2020. P. 13].

Some researchers highlight the role of MDBs in development banking as norm promoters [Mendez, Houghton 2020] and agenda-setters: “the development banks have shaped thinking about what development means and how to go about it” [Bazbauers, Engel 2021. P. 2]. MDBs have carried out substantial pioneering research in the sustainable development sphere [Bhattacharya et al. 2018], publish reports on sustainable development [Gable et al. 2015], and maintain databases. The NDB does not have any publicly available reports or databases in the sphere, however, it made an important step as promoter of the local currency bond market with bond programs in Chinese renminbi, South African rand, and Russian rubles, and 20.8% of loans made in local currencies of member countries (cumulative share, NDB, 2023).

And the great majority of researchers stress the mobilization effect of MDBs in sustainable finance [Broccolini et al. 2020, Avellan et al. 2022, Artecona et al. 2019, Bhattacharya et al. 2018]. This function has even been placed at the center of the sustainable development financing system. For example, the World Bank states that projects should be financed with public funding only if there is no sustainable private sector solution [OECD 2021b. P. 372], and international organizations increasingly use the term “blended finance” defined as “the strategic use of development finance for the mobilization of additional finance towards sustainable development in developing countries” [OECD 2018]. It is estimated that development bank-backed blended finance can be leveraged at 9:1 ratio [Kenny 2019. P. 1]. The NDB also contributes to the mobilization of sustainable finance: for example, based on the data for projects where the total value of a project is available, authors calculated that USD 33 billion provided by the NDB was allowed to finance projects totaling more than USD 80 billion. At the same time we must note that some of the finance was added by local government entities, so one has to be cautious when talking about the mobilization effect and only take into account the attraction of private finance, rather than just the total project cost.

Overall, MDBs, and the BRICS’ NDB in particular, play an important role in global development, especially given the challenges associated with global governance in the current geopolitical circumstances. They are obligated to participate and possibly take the lead in resolving a new set of problems amid limited resources and shifting priorities. Disruption of global logistics and supply chains – for various reasons and in various different ways – will inevitably lead to countries making new attempts to achieve autonomy and independence. 1

The new hybrid format is coming, with the high intensity of trade regionalization, friend-shoring, and the trend toward self-sufficiency with regards to essential commodities and technologies. Investment projects will reflect not only development needs, financing and technologies, but also issues regarding sanctions, compliance and export market restrictions. The development objectives will be extremely difficult to reach in such a tough environment.

Data and methodology

The New Development Bank has a special role in sustainable development. From the beginning, it was mandated to “mobilize resources for infrastructure and sustainable development projects in BRICS and other emerging and developing countries” [BRICS 2014]. As the previous section showed, it contributes to all four areas of MDB support to sustainable development.

Moreover, each one of the NDB’s projects can be aligned with sustainable development goals. The Bank itself has developed a special evidence-based method to monitor and report on the alignment of the Bank’s financing with the SDGs, and published these results in its annual report. This constitutes a major difference as compared with other key development banks such as the World Bank and three large regional banks (ADB, AfDB, IADB). Though they mention SDGs in annual reports, all these banks have adopted various social and environmental strategies and align their operations with the SDGs, and they do not regularly publish the direct contribution to SDGs of their projects in their reports or project descriptions.

In this research, we have improved the methodology proposed by the New Development Bank. The Bank aligns each project only with one primary goal, whereas other projects have a number of goals, such as the Pará Sustainable Municipalities Project2, which develops municipalities in three areas: road paving, sanitation improvement and enhancement of digitalization. As a consequence, this contributes to three different SDGs, all of which are equally important. Thus, we aligned each of the projects approved by the NDB with all of the goals it can contribute to.

In order to calculate the contribution of NDB projects to the SDGs, we analyzed the list of projects publicly available on the NDB website. The list contains 126 projects. Of these, there are 94 approved projects, 27 proposed and 5 cancelled. For the purposes of our analysis we took only the approved projects, totaling USD 33 billion. After that we used the following scheme:

- First, we selected only approved projects, including technical assistance;

- Second, we aligned each of the 94 approved projects with the SDGs it can contribute to, using publicly available project description and SDG targets and indicators. We counted only direct impact, not taking into account, for example, potential economic benefit for rural households from improved road connection, or effect of improved sanitation on community health.

- Third, we summarized the number of projects and the loan amounts in the table. Since one project may be attributed to a number of goals, the sum of the projects’ value exceeds USD 33 billion, and the number of projects exceeds 94. In case of loan currencies other than USD, we used the exchange rate on the date of project approval to convert the loan value into USD.

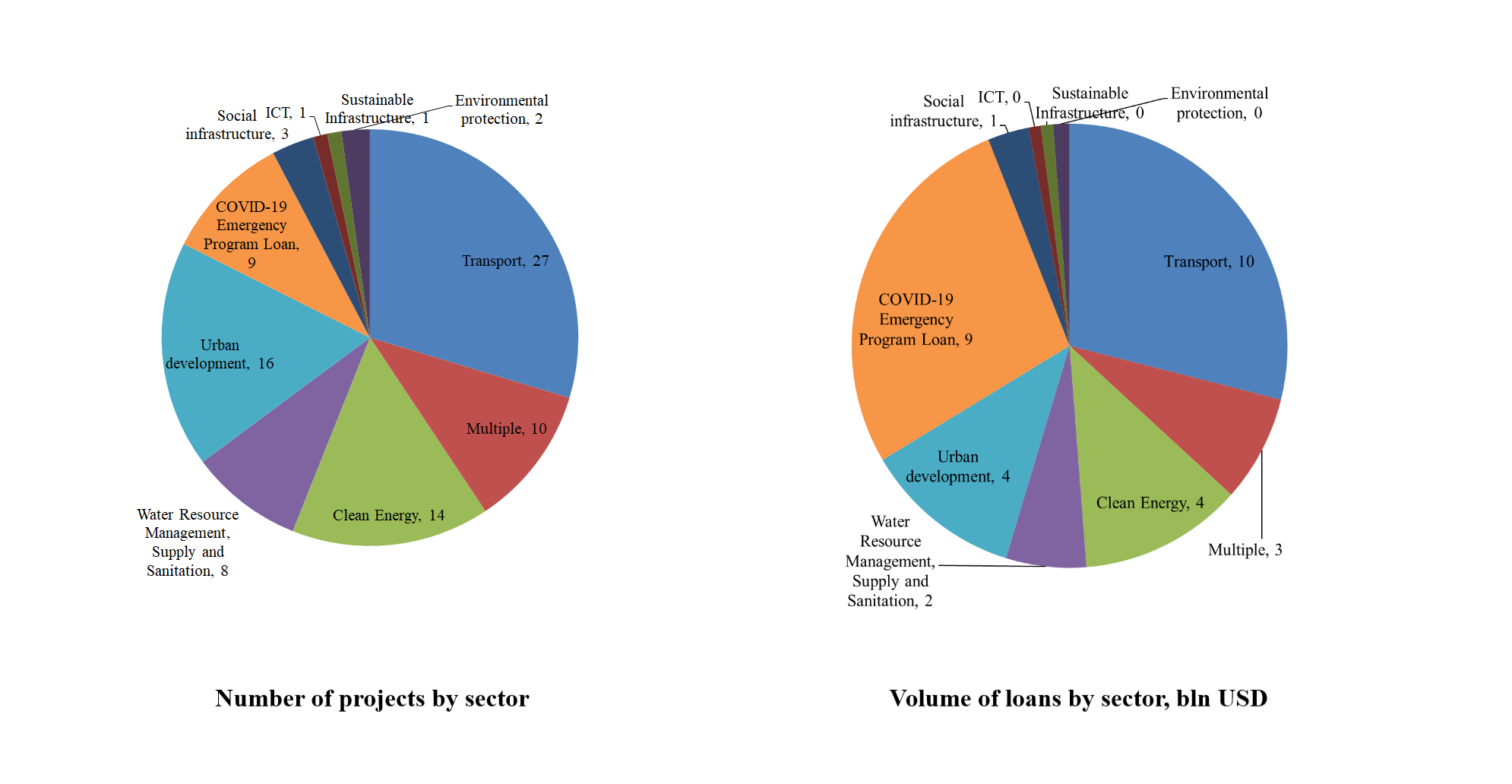

Sector breakdown might be a primary draft of projects’ contribution to the SDGs, except for the COVID-19 emergency loans and multisector loans. This primary analysis shows the large number of infrastructure projects, including transport, social and sustainable infrastructure. In second place we can see clean energy with 14 projects and USD 4 billion. Thus we might deduct that the main goal that NDB contributes is Goal 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) and Goal 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy). At the same time, the sector cannot be used as a precise evaluation of projects’ contributions to an SDG, as some projects may contribute to several SDGs within one sector. For example, the Sorocaba Mobility and Urban Development Project3 contains measures aimed at both improvement of urban planning (Goal 11) and road infrastructure (Goal 9). Another challenge with the sectorial breakdown is related to indirect association of the sector with the SDG. For example, as two out of three social infrastructure projects are related to education (Teresina Educational Infrastructure Program4 and Development of Educational Infrastructure for Highly Skilled Workforce5), measures provided by the Judicial System Support Project6 are contributing more to the upgrade of physical ICT infrastructure in the judicial sphere. In the next part we will look into the alignment of the bank’s operations with the SDGs in more detail.

Figure 2. NDB projects by sector, number and volume (USD bln), 2023

Source: NDB (n.d.)

The NDB in sustainable development

The New Development Bank has approved a set of documents governing its environmental and social activities, including: Environmental and social framework, environmental and social guideline, sustainable financing policy framework. These ensure the environmental and social soundness and sustainability of operations and support integration of these aspects into the decision-making process, including project approval and the usage of green and sustainability instruments. The basic document is the “Environment and Social Framework” [NDB 2016], which sets the categories for projects according to their social and environmental impact: A -significant adverse impact; B - less adverse than A; C - minimal or no impact. This information is publicly available for all of the projects on NDB’s portal. Also there is a rule that if the project is conducted using the financial intermediary (e.g. the loan is given to another bank or fund), and has a significant negative impact (category A), it has to be approved directly by the NDB’s Board of Directors [NDB 2016. P. 8].

The NDB’s portfolio directly contributes to achieving 12 out of 17 SDGs (Table 2). We can see that as we expected, a large portion of NDB investment contributes to SDG 9, with 49 projects containing at least one measure related to this goal. This is consistent with the bank’s mandate, which highlights infrastructure as a primary sector of investment. Also, the next largest goal by the number of projects is Goal 7, as the sectorial breakdown showed, whereas by the project volume the second place is held by SDG 8.

Table 2. The NDB’s cumulative project approvals by primary SDG alignment

|

SDG Alignment |

Number of projects |

Cumulative approvals (USD mln) |

Share of total project value (%) |

|

SDG 1. No poverty |

3 |

3,000 |

8.9 |

|

SDG 2. Zero hunger |

1 |

300 |

0.9 |

|

SDG 3. Good health and well-being |

6 |

4,214 |

12.6 |

|

SDG 4. Quality education |

3 |

650 |

1.9 |

|

SDG 6. Clean water and sanitation |

17 |

4,406 |

13.1 |

|

SDG 7. Affordable and clean energy |

20 |

5,990 |

17.8 |

|

SDG 8. Decent work and economic growth |

14 |

8,476 |

25.2 |

|

SDG 9. Industry, innovation and infrastructure |

49 |

15,293 |

45.5 |

|

SDG 11. Sustainable cities and communities |

15 |

4,942 |

14.7 |

|

SDG 13. Climate action |

2 |

600 |

1.8 |

|

SDG 16. Peace, justice and strong institutions |

1 |

460 |

1.4 |

Source: Author’s calculations based on NDB (n.d.)

These results are somewhat different from the SDG alignment published in the annual report. The first and main reason behind this is the methodology, which allows us to count more projects as related to a particular goal. For example, the NDB’s results show 24 projects contributing to Goal 9 with USD 8 billion in investment. However, there are projects with a minor contribution to this goal, which are not counted, so our estimations show a much higher number, 49 projects. Unfortunately, there is no publicly available information on the financing of the sub-projects, which means we cannot be more precise in estimations of financial contributions to particular SDGs. Thus, the whole project cost is included in each goal it contributes to. The second reason is the updated data in our research, as the results in the annual report do not count 10 projects in this field approved in 2022-2023.

As a part of its sustainability strategy, the NDB publishes SDG-related targets and planned results in its annual report (Table 3). These expected results are available only for those targets where the alignment with the SDGs and potential impact is clear and quantifiable. For example, three projects identified as having an impact on SDG 1 (No poverty) are the COVID-19 Emergency Loans7. One of their goals was stated as strengthening social safety nets, which coincides with targets 1.3 (Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable) and 1.5 (By 2030, build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social and environmental shocks and disasters) [UN 2015]. However, there were no specific estimates of the number of people affected in project documentation.

Table 3. Expected SDG impact of the NDB’s operations

|

Development indicators |

Expected outcome |

SDG alignment |

|

Schools to be built or upgraded |

58 |

SDG 4. Quality education |

|

Sewage treatment capacity |

535,000 m3/day |

SDG 6. Clean water and sanitation |

|

Drinking water supply capacity to be increased |

159,000 m3/day |

SDG 6. Clean water and sanitation |

|

Water tunnel/canal infrastructure to be built or upgraded |

1,300 km |

SDG 6. Clean water and sanitation |

|

Renewable and clean energy generation capacity to be installed |

2,800 MW |

SDG 7. Affordable and clean energy |

|

Roads to be built or upgraded |

15,300 km |

SDG 9. Industry, innovation and infrastructure |

|

Bridges to be built or upgraded |

820 |

SDG 9. Industry, innovation and infrastructure |

|

Urban rail transit networks to be built |

230 km |

SDG 11. Sustainable cities and communities |

|

Cities to benefit from NDB’s urban development projects |

40 |

SDG 11. Sustainable cities and communities |

|

CO2 emissions to be avoided |

5.5 mln tons/year |

SDG 13. Climate action |

Source: NDB (2021) Annual report 2020, p. 9. https://www.ndb.int/governance/transparency-reporting/

Thus, our analysis show that the NDB primarily contributes to the goals that raise the least number of questions in terms of changed circumstances, such as SDG 6, SDG 7, SDG 8, and SDG 9. Similar results with highlighting SDGs 7 and 9 were obtained using a case study approach based on 5 NDB projects [Braga, de Conti, Magacho 2022]. Other researchers also highlight the share of projects classified as sustainable infrastructure (60.4 per cent by the end of 2019), which is a strong signal of the NDB’s commitment to sustainability [Humphrey 2020].

However, as research on the effect of the crisis on the SDGs primarily shows, the main challenges are associated with goals 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, and 10. In order to be an important player in global sustainable development, the NDB must pay special attention to these fields. It is true that the bank already has some projects aimed at these particular goals, and that they are mostly directly associated with the COVID-19 Assistance Program. For example, three projects with SDG 1 association are the three first COVID-19 Emergency Programme Loans to Brazil8, South Africa9 and India10. In all the programs there are measures aimed at maintenance of minimum income levels for vulnerable groups and improvement of social safety nets (Goal 1.3). SDG 2 becomes particularly important in the current crisis under rising agriculture prices, however, there is only one project associated with this goal, but only with a limited impact as this is a contribution to “Indian National Investment and Infrastructure Fund: Fund of Funds (FoF)”11. FoF focuses on key socioeconomic areas of the Indian economy, however, NDB does not have a direct influence on the project themes, and there might be no contribution to SDG 2 in the end. Five projects are associated with the extremely important SDG 3; however, they include the already discussed investment in FoF and COVID-19 Emergency Program Loans in South Africa and India, adding two COVID-19 Emergency Program Loans in China12 and Russia13 supporting the countries’ healthcare sectors. SDG 10 is not present in NDB’s projects, however, the bank’s activities may have an indirect impact on those living in vulnerable rural and remote communities by improving infrastructure and therefore minimizing transfer costs.

Micro-level analysis of NDB projects and their contribution to the SDGs showed the prevalence of infrastructure and growth effect of the bank’s activities. At the same time, the bank quickly stepped in during the pandemic in 2020 and provided loans aimed at social issues such as social protection, education, and healthcare.

However, at the moment, the NDB and overall system of global development assistance are facing unprecedented challenges. Multilaterals are running the crisis management and stabilization of the global economy. Increasingly probable stagflation keeps the IMF and the World Bank busy. The UN is busy dealing with the effect on the developing world and corresponding SDGs. Meanwhile we would stress the urgency of creating some practical approaches for these new, difficult and mostly unexpected challenges to humanity.

As the BRICS countries often position themselves as centers of expertise for the developing world, they are able to develop ambitious solutions aimed at countries in the global South and propose new ways of catching up.

Conclusions and recommendations

In the article we have examined the current state of the SDGs and some specific challenges to sustainable development, including the need to review some of the goals and adapt to a new global framework. In particular, there is an urgent need to develop SDG 3 and review the approaches to sustainable and resilient healthcare systems. There are several channels though which multilateral development banks could facilitate this process, including direct financing aligned with the SDGs, norm setting and agenda developing, and expertise in the field of the current challenges.

The New Development Bank, as an important player in this field and the only global multilateral bank with only developing countries as members, is in unique position to become a global rule-maker. We analyzed the relationship between the bank’s operations and the SDGs and showed the already significant contribution of the bank toward 12 out of 17 goals, especially SDG 6, SDG 7, SDG 8, and SDG 9. However, there are several potential ways to strengthen the NDB’s role in sustainable development.

First, currently, the NDB’s role as a norm setter and agenda developer might be enhanced greatly. Right now it is limited to promotion of local bond markets, whereas it might take an active role in shaping the new SDG agenda, taking into account the current challenges uncovered by the latest global crises, including inequality, poverty, food security, and healthcare. Publishing reports on the SDGs, and best practices of projects alignment to the SDGs are only a few possibilities in terms of playing a larger role in the field.

Second, our analysis showed that there is scope for increased transparency on NDB financing by sub-projects, including different parts of the projects aimed at different SDGs. Since the NDB positions itself as a bank aimed at promotion of sustainable development, it may more clearly articulate projects’ contributions to the SDGs. In some projects this happens, but most lack this kind of data.

Third, the NDB should pay more attention to contemporary challenges facing global society, including rising inequality. SDG 10 is a critical junction – 2020-2021 and 2022 have brought more inequality inside and between countries [World Inequality Lab 2022]. Only if we pay special attention to these critical aspects of global development might the future of the world look brighter.

Bibliography

The Asian Development Bank (ADB), 2023. ADB Annual Report 2020. Available at: https://www.adb.org/documents/adb-annual-report-2020African Development Bank (AfDB), 2023. African Development Bank Group Annual Report 2022. Available at: https://www.afdb.org/en/annualreport

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), 2023. 2022 AIIB Annual Report. Available at: https://www.aiib.org/en/news-events/annual-report/overview/index.html

Artecona, R., Bisogno, M., Fleiss, P., 2019. Financing development in Latin America and the Caribbean: the role and perspectives of multilateral development banks. Studies and Perspectives series - ECLAC Office in Washington, D.C., No. 19.

Avellan, L., Galindo, A. J., Lotti, G., Rodriguez, J.P., 2022. Bridging the gap: mobilization of multilateral development banks in infrastructure. IDB Working Paper Series #1299.

Bazbauers, A.R., Engel, S., 2021. The Global Architecture of Multilateral Development Banks: A System of Debt or Development? Abingdon: Routledge.Bhattacharya, A., Kharas, H., Plant, M., Prizzon, A., 2018. The New Global Agenda and the Future of the Multilateral Development Bank System. International Organizations Research Journal, 13(2), pp.101 - 124. DOI: 10.17323/1996-7845-2018-02-06.

Bobylev, S.N., and Grigoryev, L.G., 2020. In search of the contours of the post-COVID Sustainable Development Goals: The case of BRICS. BRICS Journal of economics, 1(N2). https://doi.org/10.38050/2712-7508-2020-7

Braga, J. P., De Conti, B., Magacho, G., 2022. The New Development Bank (NDB) as a mission-oriented institution for just ecological transitions: a case study approach to BRICS sustainable infrastructure investment. Revista Tempo do Mundo, (29), pp.139 - 164. DOI:10.38116/rtm29art5

BRICS, 2014. Agreement on the New Development Bank. Available at: https://www.ndb.int/wp-content/themes/ndb/pdf/Agreement-on-the-New-Development-Bank.pdf

Broccolini, C., Lotti, G., Maffioli, A., Presbitero, A., Stucchi, R., 2020. Mobilization Effects of Multilateral Development Banks. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper #9163. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33395

EC, 2021. Life expectancy decreased in 2020 across the EU. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/product/-/asset_publisher/VWJkHuaYvLIN/content/id/12645457/pop_up

Gable, S., Lofgren, H., Rodarte, I.O., 2015. Trajectories for Sustainable Development Goals: Framework and Country Applications. World Bank, Washington, DC. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/23122

Griffith-Jones, S., 2016. Development Banks and their key roles: Supporting investment, structural transformation and sustainable development. Discussion Paper 59, Bread for the World. Available at: https://www.stephanygj.net/papers/Development_banks_and_their_key_roles_2016.pdf

Griffith-Jones, S., Gottschalk, R., 2012. Exogenous Shocks: Dealing with the only Certainty: Uncertainty (The Initiative for Policy Dialogue, Policy Brief #8). Paper prepared for the Commonwealth Secretariat, September 2012, for the Commonwealth Finance Ministers’ Meeting, Tokyo, 10 October 2012. Available at: https://policydialogue.org/publications/policy-briefs/exogenous-shocks-dealing-with-the-only-certainty-uncertainty/

Grigoryev, L.M., and Medzhidova, D.D., 2020. Global energy trilemma. Russian Journal of Economics 6 (2020) pp.437 - 462. DOI 10.32609/j.ruje.6.58683

Grigoryev, L.M., Elkina, Z.S., Mednikova, P.A., Serova, D.A., Starodubtseva, M.F., and Filippova, E.S. 2021.The perfect storm of personal consumption. Voprosy Ekonomiki. 2021. No. 10), pp.27-50. (in Russian). Available at: https://doi.org/10.32609/0042-8736-2021-10-27-50

Grigoryev, L.M., Morozkina, A.K., 2022. Pandemic shock and recession: the adequacy of anti-crisis measures and the role of development assistance. In COVID-19 and Foreign Aid: Nationalism and Global Development in a New World Order, Eds: Jakupec, V., Kelly, M., de Percy, M. Routledge, 344 P. (forthcoming)

Handl, G., 1998. The Legal Mandate of Multilateral Development Banks as Agents for Change Toward Sustainable Development. The American Journal of International Law, Vol. 92, No. 4, pp.642 - 665

Humphrey, C., 2020. From drawing board to reality: the first four years of operations at the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000411422

Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), 2022. . Annual Report 2022. Financial Statements. Available at: https://publications.iadb.org/en/inter-american-development-bank-annual-report-2022-financial-statements

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2021. Financing Global Health 2020: The impact of COVID-19. Seattle, WA. Available at: https://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/policy_report/FGH/2021/FGH_2020_full-report.pdf

IMF, 2021, Economic Outlook. Recovery During a Pandemic. Health Concerns, Supply, Disruptions, and Price Pressures. Washington, DC, October. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2021/10/12/world-economic-outlook-october-2021

Kenny C., 2019. Marginal, Not Transformational: Development Finance Institutions and the Sustainable Development Goals. CGD Policy Paper 156. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. Available at: https://www.cgdev.org/publication/marginal-not-transformational-development-finance-institutions-and-sustainable

Liu Z. et al, 2021. Global Daily CO2 emissions for the year 2020. Researchgate. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349759072_Global_Daily_CO_2_emissions_for_the_year_2020

Mendez, A., Houghton, D.P., 2020. Sustainable Banking: The Role of Multilateral Development Banks as Norm Entrepreneurs. Sustainability. 12, 972; DOI:10.3390/su12030972

Morozkina, A.K., 2019. Official Development Aid: Trends of the Last Decade. World Economy and International Relations, 2019, 63(9), pp.86 - 92. DOI: 10.20542/0131-2227-2019-63-9-86-92 (in Russian)

NDB, 2016. Environment and Social Framework. Available at: https://www.ndb.int/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/ndb-environment-social-framework-20160330.pdf

NDB, 2021. Annual report 2020. Available at: https://www.ndb.int/data-and-documents/annual-reports/

NDB, 2023. Investor Presentation. Available at: https://www.ndb.int/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Investor-Presentation_2023.pdf

NDB, n.d. List of all projects [dataset]. NDB. Available at: https://www.ndb.int/projects/list-of-all-projects/

OECD, 2018. OECD DAC Blended Finance Principles: Unlocking Commercial Finance for the Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: https://web-archive.oecd.org/2022-08-19/469783-OECD-Blended-Finance-Principles.pdf

OECD, 2021a. Development co-operation during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of 2020 figures and 2021 trends to watch, in Development Co-operation Profiles, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/e4b3142a-en.

OECD, 2021b. Development Co-operation Report 2021: Shaping a Just Digital Transformation, OECD Publishing, Paris. DOI: 10.1787/ce08832f-en.

OECD, n.d. International Development Statistics (IDS) online databases [dataset]. OECD. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-data/idsonline.htm

Our World in Data, n.d. Our World in Data [database]. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/

Sachs, J.D., Kroll, C., Lafortune, G., Fuller, G., and Woelm, F. 2021. Sustainable development report 2021. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. DOI: 10.1017/9781009106559

UN, 2015. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. UN. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

UN, 2020. UN Secretary-General appoints 15 independent scientists to draft the second quadrennial Global Sustainable Development Report. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/news/un-secretary-general-appoints-15-independent-scientists-draft-second-quadrennial-global

UN, 2021. The Sustainable Development Goals Report. NY: United Nations Publications. Available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2021.pdf

UN, 2023. Global Sustainable Development Report 2023. NY: United Nations Publications. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/gsdr/gsdr2023

UNESCO, 2021. Education: From Disruption to Recovery. UNESCO. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse.

World Bank, 2023. The World Bank Annual Report 2022. A New Era in Development. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099092823161580577/BOSIB055c2cb6c006090a90150e512e6beb

World Bank, n.d. World Development Indicators Database [dataset]. World Bank. Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

World Inequality Lab, 2022. World Inequality Report 2022. Available at: https://wir2022.wid.world/

Notes

1 For example, establishment of independent mechanisms such as new financial settlement mechanisms, bilateral and multilateral trade agreements, climate-related country-specific goals etc.

2 New Development Bank. Pará Sustainable Municipalities Project https://www.ndb.int/project/para-sustainable-municipalities-project-brazil/

3 New Development Bank. Sorocaba Mobility and Urban Development Project. https://www.ndb.int/project/xian-xianyang-international-airport-phase-iii-expansion-project/

4 New Development Bank. Teresina Educational Infrastructure Program. https://www.ndb.int/project/brazil-teresina-educational-infrastructure-program

5 New Development Bank. Development of Educational Infrastructure for Highly Skilled Workforce. https://www.ndb.int/project/russia-development-educational-infrastructure-highly-skilled-workforce/

6 New Development Bank. Judicial System Support Project. https://www.ndb.int/project/judicial-support-russia/

7 New Development Bank. COVID-19 Emergency Program for South Africa https://www.ndb.int/news/ndb-board-directors-approves-usd-1-billion-covid-19-emergency-program-loan-south-africa/

8 New Development Bank. Emergency Assistance Program in Combating COVID-19. Brazil. https://www.ndb.int/project/brazil-emergency-assistance-program-combating-covid-19/

9 New Development Bank. COVID-19 Emergency Program. South Africa. https://www.ndb.int/project/south-africa-covid-19-emergency-program/

10 New Development Bank. Emergency Assistance Program in Combating COVID-19. India. https://www.ndb.int/project/india-ndb-emergency-assistance-program-combating-covid-19/

11 New Development Bank. National Investment and Infrastructure Fund: Fund of Funds – I https://www.ndb.int/project/india-national-investment-infrastructure-fund-fund-funds/

12 New Development Bank. NDB Emergency Assistance Program in Combating COVID-19. https://www.ndb.int/project/india-ndb-emergency-assistance-program-combating-covid-19/

13 New Development Bank. COVID-19 Emergency Program Loan for Supporting Russia’s Healthcare Response. https://www.ndb.int/project/covid-19-emergency-program-loan-for-supporting-russias-healthcare-response/

1.jpg)