Digital Trans-Boundary Initiatives of the ASEAN Economic Community as a Tool for the Development of Singapore’s Economy

[Чтобы прочитать русскую версию статьи, выберите русский в языковом меню сайта.]

Evgeny Kanaev – Dr.Sc. (History), professor of the Faculty of World Economy and International Affairs, HSE University.

ORCID: 0000-0002-7988-4210

Dmitry Fedorenko – master’s graduate, HSE University.

ORCID: 0009-0000-8831-5821

For citation: Kanaev, E., Fedorenko, D., 2024. Digital Trans-Boundary Initiatives of the ASEAN Economic Community as a Tool for the Development of Singapore’s Economy. Contemporary World Economy, Vol. 2, No 1.

Keywords: Singapore, digital transformation, ASEAN Economic Community, multilateral cooperation, data localization, data centers, development tools.

Abstract

This article seeks to clarify the potential for digital collaboration between the Republic of Singapore and its partners in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) within the framework of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) as a means of stimulating economic growth in Singapore. The paper traces the features of economic modernization of the Republic of Singapore and assesses the efficiency of its approach to digital transformation of its economy. The article reveals Singapore’s approach to the integration initiatives undertaken by ASEAN, with a special focus on AEC. It also identifies the possibilities of providing effective digital support for multilateral trans-boundary economic projects within the ASEAN framework. The latter is analyzed through the prism of infrastructure development and digital competencies in ASEAN countries as well as the specifics of their regulation of cross-border digital flows and the development of data centers. Special attention is paid to the role of global value chains (GVCs) in Southeast Asia (SEA) as a key success factor behind ASEAN cross-border digital projects. The authors argue that negative integration, a cornerstone of ASEAN economic regionalism initiatives, undermines the digital transformation of the ongoing projects. This ultimately constrains Singapore’s capacity to leverage the cooperative frameworks and mechanisms established with its AEC partners to diversify and strengthen the foundations of its domestic economic growth. The study’s relevance is premised upon two factors: the timeliness of its focus on the digital cooperation between ASEAN countries ahead of the second completion of the ASEAN Economic Community establishment, scheduled for 2025, and the limitations of the modernization strategy implemented by the Republic of Singapore amidst its sixtieth anniversary of independence. The scientific and practical significance of the study stems from its focus, as the possibilities of “resetting” the Singaporean version of new industrialism in synergy with the policy of the Republic of Singapore towards the ASEAN Economic Community, as well as the implementation of multilateral cross-border digital projects by the Association, have not yet been an area of research by Russian and foreign scholars.

Introduction

The Republic of Singapore is one of the four so-called “Asian Tigers”—economies that have moved “from the Third World to the First World” with the help of a development model based on export promotion with an optimal combination of state support and market mechanisms. However, since the early 2000s, the growth rate of the Singaporean economy has slowed down, necessitating a search for alternative instruments of economic development that are not contingent on exports.

The Singaporean leadership identifies the digital transformation of the economy and society as a key instrument for economic development. Participation in integration initiatives, including digital ones, undertaken under the auspices of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations is a significant component and simultaneously a direction of Singapore’s policy [The Ministry of Trade and Industry 2023; Singapore Declaration 2024].

Nevertheless, the realities of integration in Southeast Asia indicate that ASEAN lacks effective instruments to digitalize large cross-border initiatives and enhance their impact. Moreover, Singapore demonstrates a greater degree of digital maturity than the majority of its ASEAN partners. It would be unwise, therefore, to exaggerate the impact of the ASEAN Economic Community and its digital initiatives on the Republic of Singapore’s ability to acquire additional development tools.

The objective of this article is to assess Singapore’s capacity to leverage ASEAN multilateral initiatives and their digital components as a means to enhance the competitiveness of its economy, particularly in light of the country’s ongoing economic modernization.

The research methodology is based on statistical and comparative analysis. It aims at identifying key trends in Singapore’s economic development and to assess the interim results of its public policies, in particular, support for digital tools and practices.

The paper starts with a qualitative and statistical analysis of the distinctive features of the Republic of Singapore’s economic development, with a particular emphasis on its digital component. Then, the authors clarify the role of the ASEAN Economic Community in Singapore’s external economic policy, particularly in terms of its potential for leveraging ASEAN integration mechanisms as a driver of economic growth. The third section focuses on the potential for the unification of digital cooperation in Southeast Asia, which is a crucial factor in the successful implementation of ASEAN multilateral projects and a stimulus for the development of the Singaporean economy. The final section summarizes the foregoing analysis.

Economic development of the Republic of Singapore and its digital dimension

Following its independence in 1965, Singapore started a process of economic modernization. Due to its geographical features and inherent limitations, including a relatively small population (in 1965, the city-state had a population of 1.9 million), Singapore opted for a strategy of fostering the growth of export-oriented and technologically-advanced industries. One of Singapore’s key advantages, both at the time and in the present period, is its geographical location, which facilitated the development of logistics and re-exports, as well as shipbuilding. Additionally, a deficit-free budget, a stable exchange rate for the Singapore dollar, and a high mandatory reserve ratio for commercial banks were crucial factors.

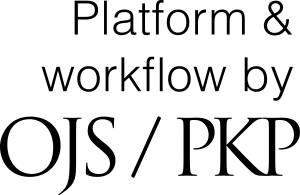

In such circumstances, the Singaporean government opted for the advancement of large state-owned enterprises and the establishment of supportive financial structures. In addition to the favorable geographical location and cheap labor, the Singaporean government sought to attract foreign investors by reducing taxes and ensuring the transparency of legislation. Consequently, in 1968 Texas Instruments [National Library Board] commenced semiconductor production on the island, and in 1969 another American company, National Semiconductor [NTU Singapore], followed suit. This policy of attracting foreign manufacturers, reinforced by parallel programs of infrastructure construction, ease of doing business, and person-power training, yielded positive results: between 1976 and 1999, Singapore’s merchandise exports grew from $6.6 billion1 to $114.7 billion, a 17.4-fold increase (see Figure 1), with an average annual growth rate of 14.4%. From 2001 to 2023, there was a fourfold increase in merchandise exports, with an average annual growth rate of 7.1%.

Figure 1. Singapore’s merchandise exports in 1965–2023, $ billion

Source: UNCTAD.

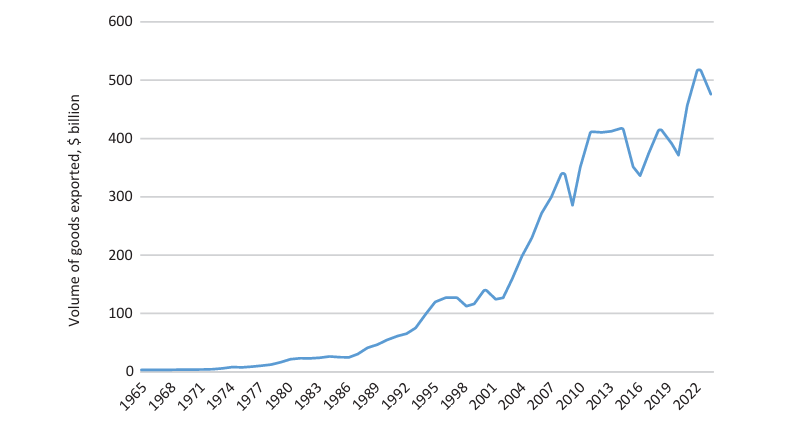

The attraction of foreign manufacturers for the needs of Singapore’s industry, as well as the service sector, primarily banking and insurance, enabled the city-state to facilitate the development of linked industries and, most crucially, human capital, thereby enhancing the quality of the workforce. In Northeast Asia, Hong Kong, Taiwan and the Republic of Korea implemented similar modernization strategies. During the 1970s and 1980s, the non-communist countries of Southeast Asia, which, along with Singapore, joined ASEAN, also began to attract foreign investors with the objective of developing production on their territory, relying on the availability of cheap labor resources. These factors incentivized Singapore to increase its effort and, in the 1970s, the country began to implement an export-oriented economic model. The latter focused on the production and supply of high-value-added products to the global market, including electronics, energy equipment, petroleum products, chemical products, and a number of other items.

Figure 2. Export revenue of Singapore’s main commodity groups in 2001 and 2023, $ billion.

Source: Trademap.

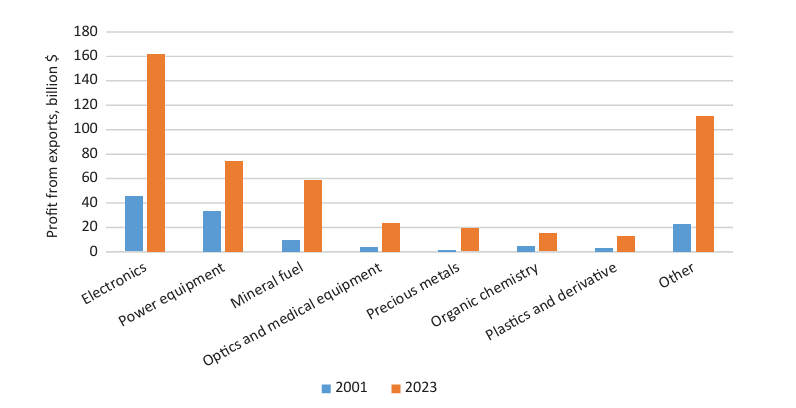

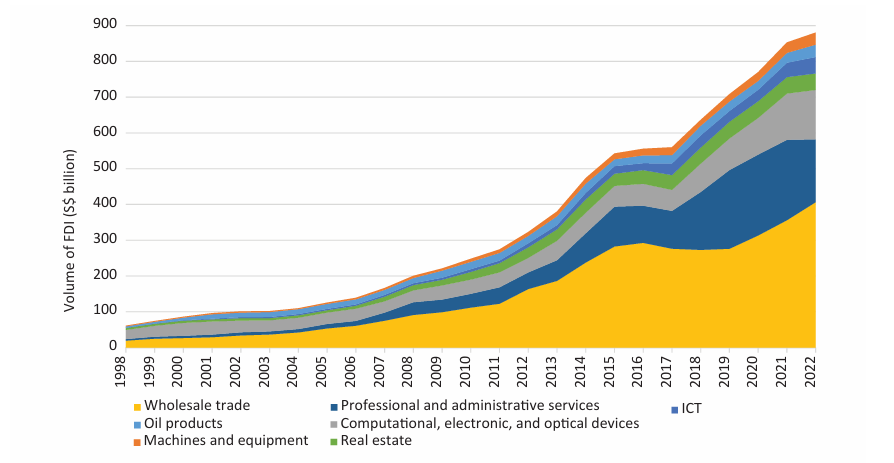

The industrialization of Singapore has been a notable success, reflecting the country’s transformation into the most economically developed nation in Southeast Asia. The dynamics of attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) into the economy of the Republic of Singapore provides compelling evidence to support this assessment. From 1979 to 2000, foreign investment in Singapore’s equity capital increased 20.7 times, with an average annual growth rate of 16%. In the subsequent period (from 2000 to 2022), the volume of investment grew 13.9 times, with an average annual growth rate of 13% (see Figure 3). Concurrently, the majority of investment was allocated to holding structures, computer, electronics and optics industries, and retail trade [Department of Statistics Singapore 2024a].

Figure 3. Year-end cumulative FDI in Singapore from 1970 to 2022, S$ billion

Source: Department of Statistics Singapore, 2024b.

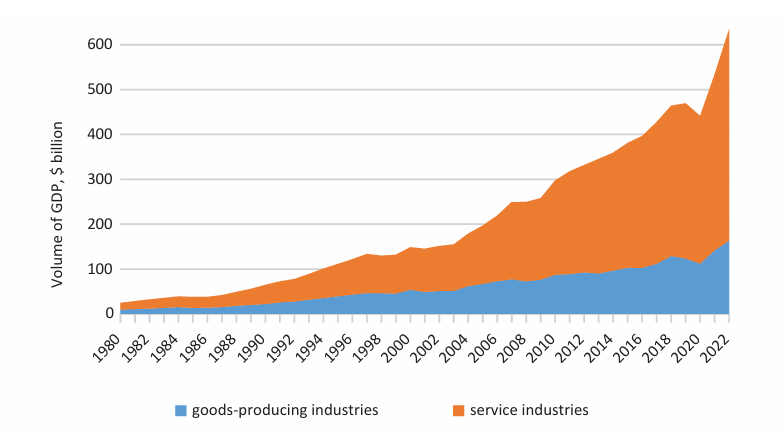

A significant factor contributing to Singapore’s economic prosperity has been the stability of its financial system. This has been a key focus for the country’s leadership, who have demonstrated a commitment to enhancing this stability through various measures. Consequently, due to the prudent management of accumulated reserves and the adept deployment of financial resources, the country not only demonstrated resilience encountering the Asian financial and economic crisis of 1997-1998 and the global financial crisis of 2008 [Singapore Government, SG101 2024], but also witnessed a notable expansion in accumulated foreign direct investment (FDI). Without competing with other East Asian economies, the Republic of Singapore is able to attract an increasing volume of financial flows, technological and managerial know-how, thereby enhancing its status as a regional industrial, financial, and logistic hub. The efficacy of this strategy is demonstrated in Figure 4. Since 2004, there has been a notable expansion in the service sector and its contribution to GDP, while the industrial sector has continued to demonstrate growth. This is indicative of the efficacy of Singapore’s policy of prioritizing the development of its financial and banking sectors.

Figure 4. Growth and composition of Singapore’s GDP at current prices in 1980-2022, $ billion

Source: Department of Statistics of Singapore, 2024c.

Nevertheless, a series of economic challenges have been emerging in the Republic of Singapore over an extended period. A persistent source of vulnerability has been and continues to be lack of agricultural production [International Trade Administration 2024b] and natural resources, including fresh water [International Water Association 2024]. It is also noteworthy that the country is highly dependent on imports and that exports play a disproportionately large role in its economic growth. Additionally, Singapore is facing growing competition from other regional transportation and logistics hubs, primarily located in Thailand and Malaysia. These hubs are developing their capabilities based on China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which is a significant challenge for Singapore.

The aforementioned factors impede the further economic development of the Republic of Singapore, compelling its leadership to identify alternative sources of growth. There are compelling reasons for this assessment. The proportion of GDP contributed by the service sector has increased markedly since 2003 (Figure 4). From 2000 to 2023, the average annual growth rate of total GDP (in 2015 prices) was 4.8%, while from 1976 to 1999, GDP grew at an average annual rate of 7.6% [Singapore Department of Statistics 2024d]. Importantly, the growth rate was affected by major economic crises, namely those of 1997, 2000, and 2008-2009. However, their impact was insignificant, with the exception of a 2.2% contraction in 1998. The contraction in 2001 was 1.1%, while the growth in 2008 was 1.9%. In 2009, the annualized growth rate was 0.1% [Singapore Department of Statistics 2024d]. With regard to GDP dynamics, the impact of these crises was discernible in only three of the 24 years under consideration (2000-2023).

This factor leads to the conclusion that the decline in GDP growth rates, while they were generally positive, was due to other factors. For example, a decline in industrial output in the manufacturing sector [S&P 2023] and competition from developing Asian countries may have contributed to this decline. This period also saw the development of human capital and high-value-added industries, as well as an inflow of foreign investment [Max Alston, Ivailo Arsov, and others 2018]. Similarly, the decline in growth rates was evidenced by the indicator of value added per employee, both for the economy as a whole and for the majority of industries in Singapore. From 1984 (the earliest available data point) to 1999, the average annual growth rate was 4.1%. However, between 2000 and 2023, it declined to 1.9%. This demonstrates a decrease in the output efficiency of the economy (Singapore Department of Statistics 2024 data). In this context, digital services and technologies have emerged as a significant competitive advantage, contributing to the positive growth trajectory of Singapore’s GDP. In 2023, the ICT sector ranked among the top three sectors with the highest growth rates [Ministry of Trade and Industry 2024].

Singapore occupies the fifth position in the Global Innovation Index, which was achieved in 2018 [Analytical Center under the Government of Russia 2018]. This index considers not only economic factors but also social aspects, the extent of infrastructure development, and the evolution of markets. It encompasses the majority of macroeconomic indicators, thereby facilitating a comprehensive evaluation of the country.

In considering digital tools as new sources of economic growth, the leadership of the Republic of Singapore has identified two key points. The first point to note is that the emergence and development of these sources are not so much related to internal factors, namely Singapore’s own policies, as to external factors. Secondly, Singapore must enhance its capacity to leverage these factors by developing digital tools.

From an external perspective, the establishment and expansion of digital cooperation between Singapore and its partners will assist in addressing a number of significant challenges the city-state is facing. The advancement of digital technologies in the agro-industrial sector (commonly referred to as “AgriTech”) has the potential to mitigate the severity of the food crisis in Southeast Asia, thereby enhancing Singapore’s resilience to disruptions in the supply of essential resources such as fresh water and food. As previously mentioned, Singapore lacks its own agricultural capabilities, making it particularly vulnerable to external factors influencing the availability of these resources. The reformatting of global value chains in the region along with deepening Sino-American tensions over technology (ranging from “China + 1” to “China + many”) with effective digital support will make these chains more resilient, thereby enabling Singapore to at least partially hedge risks. The participation of Singaporean companies, including MSMEs, in cross-border digital projects will enable these firms to perform tasks requiring a high level of skill without incurring significant costs. The latter are rising rapidly. In September 2023 and March 2024, the Government of the Republic of Singapore increased the salary threshold requirements for hiring foreign talent from S$4,500 to S$5,000 and from S$5,000 to S$5,600, respectively [HKTDC Research 2024].

Most importantly, the digital transformation of society will enable the Republic of Singapore to fully benefit from China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Singapore represents the nexus of the Silk Road Economic Belt (where the China-Indochina Economic Corridor culminates, connected by the Kunming-Singapore railway) and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road. As the BRI encompasses not only transportation but also industrial collaboration, the activation of which is underway in varying degrees across the countries of Southeast Asia, particularly Indochina, it will undoubtedly place significant workload on Singapore’s port infrastructure, generating substantial revenue. In the development of the Digital Silk Road, China places a significant emphasis on the provision of digital support for BRI-related projects.

In light of these considerations, the Republic of Singapore aims to use digital tools to stimulate its developmental processes. Notably, the country has established a robust record of accomplishment in this field since the 1980s. The rationale behind this decision was a necessity to address multiple challenges, mostly relating to the competition for foreign investment with neighboring countries. These states are, on average, dozens of times larger than Singapore in terms of population, and offer increased opportunities for the development of labor-intensive industries. Without attempting to completely review most significant programs and initiatives, we will focus on the key on-going program: The Smart Nation, launched in 2014. As a result of its implementation, the Republic of Singapore has become one of the global “centers of excellence” in the field of digital transformation.

Firstly, the country was among the first in the world to provide internet access to nine out of ten households, with an internet penetration rate of 96% in 2022 [World Bank 2024]. Secondly, Singapore has developed an effective economic management structure, primarily through government-affiliated companies developing digital programs both domestically and internationally. Third, the digital transformation of the economy and society has achieved a substantial and, more importantly, an expanding footing. The share of the gross domestic product (GDP) attributed to the information and communication technology (ICT) sector in Singapore increased from 3.1% in 2000 to 6.1% in 2022, according to data from the Department of Statistics of Singapore (2024d). The economic impact of Singapore’s digital transformation, including the ICT sector itself and digital support for the rest of the economy, was estimated at S$106 billion in the Singapore Digital Economy Report (2023). The implementation of programs, notably the Singapore Digital Government Blueprint in 2018, has facilitated the digital transformation of the public sector, trade, finance, industry and logistics of the Republic of Singapore. This has enabled the economy to achieve an average annual growth in the volume of value added from digital support of 12.9% from 2017 to 2022 [Singapore Digital Economy Report 2023].

The success of the Republic of Singapore in digital transformation is further evidenced by many additional examples. In 2022, the technology adoption rate among micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises reached 94.3%, defined as the use of at least one digital service by a company [Department of Statistics of Singapore 2024d]. The active adoption of digital services is facilitated by the construction of data centers (DC). In 2023, Singapore had 100 DCs, which accounted for 7% of the city’s total electricity consumption. Additionally, there were approximately 2,000 cloud service providers and 22 network infrastructure clusters [ASEANBriefing 2023]. Commercially attractive solutions in the energy sector, including tools for smart demand monitoring, demand optimization, and household efficiency improvement are if special note. The digital twin of Singapore’s power grid serves as an illustrative example of these solutions. Consequently, the implementation of digital solutions across all sectors of the city’s economy, encompassing public services, the private sector, and transnational corporations, has become widespread. The Smart Nation program has emerged as a pivotal driver of investment inflows into the Singaporean economy, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5. FDI dynamics in the top seven2 industries in Singapore by FDI volume, S$ billion

Source: Department of Statistics of Singapore, 2024e.

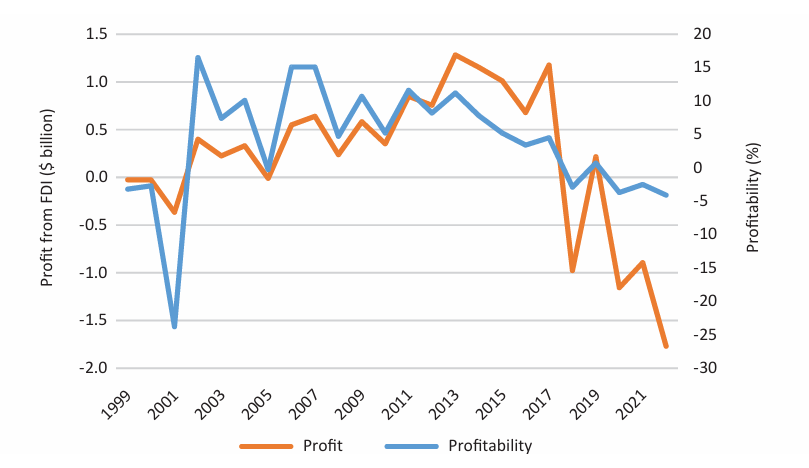

Nevertheless, the Republic of Singapore encounters a natural limit to the efficiency of digital transformation instruments. This is due to the negative dynamics of profitability and income derived from foreign direct investment (FDI) in the information and communication technology (ICT) sector, as illustrated in Figure 6. The fact that the introduction of digital technologies into Singapore’s economy is largely conducted by state-linked companies has the effect of reducing the inflow of investment. To illustrate, 55% of Singtel’s shares, one of the largest companies in the Republic, whose 5G network covered 95% of Singapore in 2022 [International Trade Administration 2024a], are owned by Temasek Holdings, which, in turn, is owned by the Singapore government [Temasek Review 2023]. Furthermore, a narrow market in comparison to neighboring countries acts as a natural barrier to the growth of return on investment.

Figure 6. Yield and income from FDI in Singapore’s ICT sector, % and $ billion

Source: Department of Statistics Singapore, 2024fg.

The aforementioned factors lead to several assessments. The digital transformation of the economy of the Republic of Singapore is progressing at a rapid pace, encompassing not only information and communication technology but also traditional sectors of the economy. Nevertheless, a number of distinctive features of Singapore, primarily the lack of opportunities to amplify economic impacts due to its narrow domestic market (which, for purposes of clarification, denotes the volume of demand, in this case from prospective Internet users), serve as intrinsic constraints to digital transformation. This prompts Singapore’s leadership and corporate sector to seek growth opportunities beyond the country’s borders.

One such area is cooperation with countries in Southeast Asia within the framework of the ASEAN Economic Community. This is aimed at establishing a unified space for industrial and commercial activities in the region, and more recently, facilitating the expansion of cross-border cooperation in the digital space. This is particularly attractive to the Republic of Singapore, given both the high level of its inclusion in the processes of digital transformation and the transition of the global economy to a new technological paradigm.

The ASEAN Economic Community in the policy of the Republic of Singapore

Cooperation with ASEAN partners has historically been a primary focus of the Republic of Singapore. The decision to establish the ASEAN Free Trade Area and the rescheduling of the ASEAN Community establishment from 2020 to 2015 were both made during Singapore’s ASEAN Chairmanship. In 2002, Singapore proposed the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community [Grzywacz 2021]. It is recognized that the principal factor contributing to the success of the ASEAN Economic Community is the establishment of a unified production and commercial space in Southeast Asia. In light of this, the Republic of Singapore is committed to supporting initiatives that contribute to narrowing intra-ASEAN development gaps. Notably, the ASEAN Integration Initiative, which commenced efforts to harmonize infrastructural development across Southeast Asia, was adopted in 2000, when Singapore acted as ASEAN Chair [ASEAN Secretariat].

Singapore has consistently been a step ahead of its ASEAN partners in undertaking joint multilateral initiatives. A case in point is Singapore’s participation in the establishment of the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area (CAFTA), which was signed in 2002 and entered into force in 2010. In addition, the Republic of Singapore concluded a bilateral free trade agreement with China in 2008 [Ministry of Commerce 2024]. Furthermore, Singapore’s emphasis on moving from the ASEAN consensus principle in economic decision-making is indicative.3 Such a shift could potentially facilitate the implementation of agreements. In general, the Republic of Singapore finds it advantageous to accelerate ASEAN economic integration processes by means of joint development of large-scale cross-border projects.

Nevertheless, the Republic of Singapore has to consider the economic realities of Southeast Asia. First and foremost, there are no GVCs established by enterprises of Southeast Asian countries that produce a multiplier effect on ASEAN multilateral projects (except those in the garment and footwear production sector). In the 1960s and 1980s, enterprises in non-communist Southeast Asian countries primarily engaged in trans-boundary activities within Japanese global value chains. Subsequently, the Association began to develop its own multilateral initiatives based on negative integration tools. The promotion of intra-industry and inter-firm cooperation through negative integration alone is insufficient for making a high-tech ASEAN product (like, for instance, an automobile, a smartphone, or another) or an ASEAN-wide tourist destination through the establishment of interconnected tourism clusters and their supporting infrastructure (Southeast Asia has been and remains an attractive destination for international tourism).

The absence of cross-border GVCs is behind the insufficient development of international transport and logistics cooperation in Southeast Asia and the varying degrees of readiness of the regional countries. With regard to the development of transport infrastructure, Southeast Asia remains a fragmented space. The implementation of major trans-boundary projects, including the ASEAN Highway Network, the establishment of a single market for sea and air transportation, and other transport and logistics initiatives, have been and continue to be hindered by the reluctance of ASEAN countries to transfer the issues of transport-related policy to the supranational level [Glazatova, Avetisyan, Aleshin 2023].

Secondly, the ASEAN Business Advisory Council (ASEAN BAC) has not responded to initial expectations. The objective of this dialogue platform is to establish incentives for the corporate sector of Southeast Asian countries, including micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises, to facilitate cross-border commercial exchanges. However, the instruments of negative integration, on which the Association premises its multilateral projects, do not pressupose the establishment of long-term inter-firm cooperation. Consequently, regular meetings, sessions, seminars, and other forms of establishing and developing professional contacts in the format of the ASEAN BAC have been held on a regular basis. However, this has not resulted in a notable increase in the scale and quality of business relations. Similarly, Singapore’s government-business dialogue platforms have not fulfilled their potential to facilitate the entry of ASEAN enterprises into each other’s markets.

Thirdly, the Association did not find it expedient to establish its own international commercial arbitration and mediation body, based on the experience of the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC), a global “center of excellence”. International commercial arbitration offers several advantages to the corporate sector, including confidentiality, a possibility to select arbitrators independently, the finality of decisions, and their binding character. A distinctive feature of SIAC is a transition from commercial arbitration to commercial mediation. This approach entails the reconciliation of the parties involved in the dispute resolution process, should they opt for such a course of action. As the Republic of Singapore hosts the headquarters of many large companies, including those from Asia-Pacific countries, Singapore and SIAC are attractive due to their well-deserved and nearly ideal business reputation. As the AEC is a large-scale and long-term project, the establishment of an ASEAN international commercial arbitration center would be in the best interests of the Association.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the US-centric Indo-Pacific Economic Framework Agreement (IPEF) exert considerable and, most importantly, growing influence on the AEC establishment and the Republic of Singapore’s related plans. With regard to ASEAN, it is evident that the BRI brings a significant degree of politicization into ASEAN economic agenda, whereas the IPEF undermines ASEAN’s capacity to act as a unified entity. Specifically, by providing assistance to Southeast Asian countries in the construction of expensive and long-term infrastructure projects, Beijing compels the Association and its member states to address regional security challenges, primarily the South China Sea issue, in a way that is advantageous to China.4 With regard to the IPEF, as seven of the Association’s ten countries are IPEF members, ASEAN plans are affected negatively, since it impedes the investment in and commercial attractiveness of Southeast Asia.

Projecting this onto Singapore’s interests, several points are noteworthy. As ethnic Chinese account for 76.2% of Singapore’s population [Singapore Academy of Corporate Management 2024], and the country is the unofficial capital of the Chinese business community in and beyond Southeast Asia, the Republic of Singapore actively participates in the BRI implementation. Simultaneously, Singapore is a member of the IPEF, which represents the economic aspect of the IPR project. The architects of this project initially did not deny its anti-Chinese character, as evidenced by Boroch, Voda, and colleagues (2020). This adds a significant degree of politicization to regional economic cooperation, which is not conducive to Singapore’s interests, given its dependence on the global economic development.

Another complicating factor is that, as yet, ASEAN countries have not created their own GVCs and tools for their upgrade. As a result, ASEAN enterprises are dependent on the ongoing models and practices. To substantiate, the COVID-19 pandemic altered priorities from a focus on speed and punctuality of deliveries (just-in-time, implies flexibility in inventory management, ideally minimizing inventory stores) to a focus on their stability and security (just-in-case, emphasizes the creation of additional, often excessive inventory stores). A substantial proportion of the logistics infrastructure is beyond Southeast Asia. Consequently, ASEAN enterprises have to adhere to the regulations established by external actors, namely those operating beyond the ASEAN area. Furthermore, they are at a disadvantage in terms of developing their own production and technological links and carrying out joint projects. These include the establishment of joint reserve facilities and emergency funds, production alliances, guarantee mechanisms of GVC transparency, etc. Additionally, a joint ESG agenda and numerous other initiatives are cases in point. These developments have a detrimental impact on Singapore’s interests, as the country has considerable experience in these areas.

In general, ASEAN lacks a unified industrial policy that would facilitate making Southeast Asia a unified manufacturing and commercial area with a multiplier effect for its member states and a positive impact on the Republic of Singapore. The more so since Singapore can assume a pivotal role in the development, branding and promotion of an ASEAN-made product or service in the global market. Therefore, it is reasonable to question whether the instruments of the ASEAN Economic Community will give the development of the Republic of Singapore a powerful impetus.

Obstacles to the Implementation of ASEAN Digital Projects

Is it plausible that the constraints of ASEAN integration, as previously discussed, could be even partially offset by digital tools, thereby enabling Singapore to expand its resources through involvement in ASEAN’s multilateral digital initiatives? There have been many such initiatives, commencing with the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Digitalization in 2000. Nevertheless, practical considerations suggest that the successful implementation of such initiatives is unlikely. This is due to a number of factors, including intra-ASEAN gaps in infrastructure development and digital competencies, as well as difficulties in establishing a unified legal framework in Southeast Asia.

Concerning infrastructure development, it is essential to acknowledge the persisting disparities in internet access across the Southeast Asian (SEA) countries. The most recent data from the ASEAN Statistical Yearbook [ASEAN 2023a] indicate that in 2022, the proportion of the population in the Southeast Asian countries with access to internet services ranged from 98.2% in Brunei to 44% in Myanmar. However, in the latter case, the issue is not infrastructural but political. A more illustrative example is the state of the 5G internet (data for some ASEAN countries are not available) (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Average and peak 5G download speed in ASEAN countries in 2023, Mbps

Source: Statista, OpenSignal.

A considerable gap between Singapore and its ASEAN counterparts (with the exception of Malaysia) in these indicators impedes the effective advancement of cross-border digital initiatives across Southeast Asia. This includes the integration of public service systems, the implementation of sectoral educational projects, programs designed to develop micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises, etc.

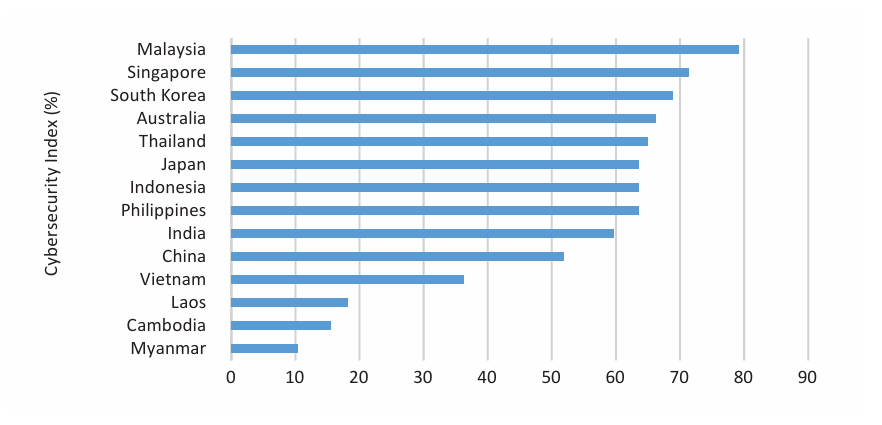

Similarly, gaps in digital competencies necessary for the effective development of economic regionalism are notable among ASEAN states. A case in point is the challenge of countering cyber threats. In 2020, 21.30% of global phishing attacks went to ASEAN financial institutions, a figure that surpasses the corresponding statistics of major technology companies, including Facebook (which has been banned in Russia), Apple, Amazon, and WhatsApp.5

Realizing how serious the threat is, ASEAN states have yet to adopt a unified approach to address it. This is largely due to discrepancies in the level of their respective competencies (for more detail, please refer to Figure 8).

Figure 8. SEA countries in the National Cybersecurity Index compared to some extra-regional ASEAN partners in 2023, %

Source: Statista.

Another pressing issue pertaining to the implementation of ASEAN multilateral digital projects is the regulation of cross-border commercial activities in the digital space.

The situation in Southeast Asia is a function of the global dimension of the problem. The norms of international law that govern doing business in the Internet space lag behind practical realities.6 Consequently, challenges in providing digital support for economic regionalism initiatives in various regions, including Southeast Asia, remain significant. This is exemplified by data localization and the establishment of data centers in ASEAN countries.

The approaches of these states to cross-border data transfers differ considerably. Indonesia and Vietnam, which adopt a restrictive approach, and Singapore, which prefers a more liberal stance, are at opposite ends of the spectrum.

The government of the Republic of Indonesia asserts that any data with relevance to national security and government operations must be stored on servers located within the country. This also applies to public service providers that include both public and private entities operating in the financial, insurance, industrial, and social sectors.7

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV) uses a comparable approach to data localization. In April 2023, a data protection law (Decree No. 13/2023/ND-CP) was enacted, requiring that all digital service providers (e-commerce, online payments, social networks, and messengers) should store information about the SRV citizens exclusively on local servers or to establish offices in the country. The legislation stipulates specific requirements for cross-border data transfers, including the creation of an Overseas Data Transfer Impact Assessment file and notification of relevant government agencies [Sangfor 2023].

The stance of the Republic of Singapore is markedly different. The implementation of data localization policies is contrary to the interests of Singapore, as it hinders the formation of the scale factor and the subsequent capitalization of cross-border digital projects. With a population of 5.637 million in 2022 [ASEAN 2023b], Singapore is interested in establishing and expanding cross-border data exchanges. In accordance with the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA), which came into force in 2021, cross-border data sharing is subject to so-called “data adequacy requirements.” These requirements stipulate that data sharing standards must be no lower than those currently in force in the Republic of Singapore. However, this is subject to the consent of the individual whose data are transferred. Moreover, the Singaporean government views the APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules as a model for data transfer [Bhunia 2018].

Other ASEAN countries have not yet adopted legislation that specifically regulates data localization. Nevertheless, an analysis of their strategies for ensuring national security and promoting foreign economic activity reveals that these states are inclined to have information, including both government and commercial data, stored on national servers.

The development of data localization across Southeast Asia is inextricably linked with data centers. The interest stems from the increasing digital transformation of economic and commercial practices and the cooperation with China in the implementation of the Digital Silk Road. The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic provided a substantial impetus to the DC development.

There are numerous examples of close attention that ASEAN countries pay to DC development. In Malaysia, the responsibility for overseeing this process is shared by several agencies whose activities are aimed at making the country more attractive to global digital companies, including Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft, GDS, Equinix, Yondr, and several others [Singh & Naharu 2023]. Thailand and Indonesia have set forth ambitious plans for the development of their data centers. The former anticipates becoming a digital corridor between India and China in collaboration with major global players in the ICT sector [Onag 2021]. The latter stakes on its population and aims to control 40% of the regional data center market by 2025 [Vietnam Plus 2021]. Additionally, the Philippines is engaged in the development of data centers, with these facilities integrated into the infrastructure component of its national vision plans [Business World 2023].

Of particular interest is the case of Vietnam, which is striving to enhance its digital and international competitiveness while simultaneously strengthening its cybersecurity (through data localization laws) and pursuing a green development agenda. While the achievements of Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Brunei have thus far been limited, their endeavors to incorporate the development and maintenance of data centers into subregional collaboration initiatives (as evidenced by the establishment of a data center in Nay Pyi Taw in September 2022 as part of the implementation of the Lancang-Mekong project [Xinhua 2022]), including in cooperation with intra-regional companies, businesses, are noteworthy.

It is evident that the Republic of Singapore has made significant advancements in the development of its data centers. Singapore has adapted to this direction by leveraging previously created and well-functioning non-digital resources, including political stability, ease of doing business, tax incentives, and numerous FTZs that serve as platforms for testing various cutting-edge digital cooperation practices. Consequently, Singapore, which has fewer data centers than some other ASEAN countries, is engaged in the process of creating DCs and optimizing their functionality (it is not appropriate to make comparisons between Singapore and Indonesia for multiple reasons). Data centers are a significant factor behind Singapore’s competitiveness as a global business hub, incentivizing multinationals to establish their headquarters. These factors increase the interest of both Singaporean and foreign businesses in investing in Singapore’s data centers, despite the limiting factors of the country’s small size, high cost of electricity, etc.

The collective impact of the aforementioned digital gaps among ASEAN member states hinders their enterprises from developing effective cross-border GVCs with digital support. The latter entails data transfers based on the integration of IT systems across various links of GVCs (which may be located in different countries), their expeditious diagnostics and prevention, the utilization of digital twins of physical objects engaged in the industrial cycle, and numerous other areas. It is also noteworthy that new and innovative areas of digital transformation have emerged, like, for instance, digital customer experience design. The lack of such support hinders the creation of a digitally supported ASEAN product or service under the “Made in ASEAN” brand, particularly in a mid-term and long-term perspective.

In general, ASEAN’s multilateral initiatives in the digital space have yet to be finalized, which is unlikely in decades to come. In light of the aforementioned considerations, it is evident that the Republic of Singapore’s aspiration to leverage the digital instruments of ASEAN integration in order to enhance its domestic economic growth is not aligned with the on-going practical realities.

Conclusion

By exploring how the Republic of Singapore implements its own development strategy, it is possible to single out the defining characteristics, potential avenues for growth, and inherent constraints of the Singaporean version of contemporary new industrialism. This approach is a transition from import substitution to an export-oriented catch-up development model that is closely intertwined with the contemporary economic integration and bolstered by digital technologies. While acknowledging the undeniable success of the Republic of Singapore in developing its economy and digital capabilities, it is imperative to recognize the necessity for new tools to provide a fresh impetus for further growth.

It is unlikely that these tools can be developed around Singapore’s involvement in ASEAN digital multilateral projects. The negative integration as the basis of ASEAN policy hinders the creation of a unified digital space, which is a crucial element for unifying conditions and opportunities for manufacturing and commercial activities. Even at the sectoral level, implementing this is challenging. Moreover, it seems unlikely that significant advances in digital support for the full range of economic relations among Southeast Asian countries can be anticipated as an independent ASEAN policy objective.

This factor not only undermines the Republic of Singapore’s plans to utilize the mechanisms of ASEAN cooperation, including digital initiatives, as a tool to stimulate economic growth, but also nullifies them. As Singapore already has a higher level of digital maturity than its ASEAN partners, it is dependent on their willingness to enhance their digital competitiveness. It is therefore reasonable to expect that the leadership of the Republic of Singapore will be compelled to reorient its priorities with respect to both the ASEAN Economic Community and ASEAN multilateral digital initiatives.

No less importantly, the Republic of Singapore’s reliance on optimal forms and methods of participation in the international division of labor based on dirigisme and Asian values may not be fully relevant to new international conditions. Present realities indicate that Singapore’s approach to new industrialism will increasingly prioritize shaping external milieu over carrying out internal transformation. These include the establishment of a novel system of production locations in Southeast Asia against the backdrop of deepening infrastructural imbalances among the regional countries, the production of “Made in ASEAN” goods and services and their integrated digital support, and other areas. The success of these developments, limited by the capacity of Singapore’s partners in ASEAN to implement necessary changes, will be a pivotal factor in the country’s economic modernization in a near-term perspective.

Bibliography

Analytical Center under the Government of Russia, 2018. Bulletin on Current Trends in the World Economy No. 36, “Singapore: Socio-Economic Foundations of Prosperity.” Available at: https://ac.gov.ru/archive/files/publication/a/18296.pdf (in Russian).

ASEAN Briefing, 2023. Singapore’s Data Center Sector: Regulations, Incentives, and Investment Prospects. Available at: https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/singapores-data-center-sector-regulations-incentives-and-investment-prospects/

ASEAN Secretariat. Initiative for ASEAN Integration & Narrowing Development Gap (IAI & NDG). Available at: https://asean.org/our-communities/initiative-for-asean-integration-narrowing-development-gap-iai-ndg/

ASEAN, 2023. ASEAN Statistical Yearbook 2023. Available at: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/ASEAN-Statistical-Yearbook-2023.pdf

Bhunia, P., 2018. Singapore Joins. APEC Cross-Border Privacy Roles for Data Controllers and Processors. OpenGovAsia. Available at: https://opengovasia.com/singapore-joins-apec-cross-border-privacy-rules-for-data-controllers-and-processors/

Borokh, O.N., Voda, K.R., et al., 2020. National and International Strategies in the Indo-Pacific. Analysis and Forecast. Moscow: IMEMO RAS. P. 124-134. Available at: https://www.imemo.ru/files/File/ru/pub l /2020/2020-009.pdf (in Russian).

Business World, 2023. PHL Data Center Capacity Set to Soar Five Times by 2025 - DICT. Available at: https://www.bworldonline.com/corporate/2023/07/27/536218/phl-data-center-capacity-set-to-soar-five-times-by-2025-dict/

Gamza, L.A., 2022. Technological Aspect of Nancy Pelosi’s Asian Tour. Moscow: IMEMO RAS. Available at: https://www.imemo.ru/news/events/text/tehnologicheskiy-aspekt-aziatskogo-turne-nensi-pelosi (in Russian).

Glazatova, M. K., Avetisyan S. S., Aleshin D. A., et al. A. et al., 2023. Evaluation of EAEU integration processes in the sphere of trade. P. 232-256. Available at: https://www.hse.ru/data/2024/03/01/2082508483/%D0%9E%D1%86%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%BA%D0%B0_%D0%B8%D0%BD%D1%82%D0%B5%D0%B3%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%86.%D0%BF%D1%80%D0%BE%D1%86 % D0%B5%D1%81%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%B2_%D0%95%D0%90%D0%AD%D0%A1_%D0%B2_%D1%81%D1%84%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B5_%D1%82%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B3%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%BB%D0%B8_2023-%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B4-2.pdf (in Russian).

GovTech Singapore, 2024. History of internet in Singapore - from niche toy to must-have essential. Available at: https://www.tech.gov.sg/media/technews/history-of-the-internet

Grzywacz, A., 2021. Singapore’s Approaches towards ASEAN Integration. ResearchGate. P. 11. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350783338_Singapore’s_approaches_toward_ASEAN_integration

HKTDC Research, 2024. Singapore: Rules Changed for Hiring Foreign Professionals. Available at: https://research.hktdc.com/en/article/MTY0NTk3Nzg5Mw#:~:text=On%204%20March%202024%20Singapore,to%20obtain%20an%20employment%20pass

Infocomm Media Development Authority, 2023. Singapore Digital Economy Report 2023. Available at: https://www.imda.gov.sg/-/media/imda/files/infocomm-media-landscape/research-and-statistics/sgde-report/singapore-digital-economy-report-2023.pdf.

International Trade Administration, 2024a. Information and Telecommunications Technology. Available at: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/singapore-information-and-telecommunications-technology

International Trade Administration, 2024b. Singapore Agriculture. Available at: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/singapore-agriculture

International Water Association, 2024. Singapore. Available at: https://iwa-network.org/city/singapore/

Interpol. Brands Most Targeted by Phishing Attacks. ASEAN Cyberthreat Assessment 2021. P. 16. Available at: https://www.interpol.int/content/download/16106/file/ASEAN%20Cyberthreat%20Assessment%202021%20-%20final.pdf

Max Alston, Ivailo Arsov, Matthew Bunny, and Peter Rickards, 2018. Developments in Emerging SouthEast Asia. Reserve Bank of Australia. Available at: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2018/dec/developments-in-emerging-south-east-asia.html

Ministry of Commerce, People’s Republic of China, 2024. China - Singapore FTA. Available at: http://fta.mofcom.gov.cn/topic/ensingapore.shtml

Ministry of Trade and Industry, 2023. ASEAN Launches Negotiations on ASEAN Digital Economic Framework Agreement and Bolsters Regional Economic Integration. Available at: https://www.mti.gov.sg/Newsroom/Press-Releases/2023/09/ASEAN-launches-negotiations-on-ASEAN-Digital-Economic-Framework-Agreement

Ministry of Trade and Industry, 2024. MTI Maintains 2024 GDP Growth Forecast at “1.0 to 3.0 Per Cent”. Available at: https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/news/gdp4q2023.ashx

National Library Board. Texas Instruments plant officially opens. Available at: https://nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=1f22a763-35e6-4587-8f50-d77b65e59b3c

NTU Singapore. Fairchild Semiconductor. Available at: https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/microelectronics/companies/fairchildsemiconductor/

Onag, G., 2021. Thailand’s EEC on Track with Digial Innovation Hub Goal. FutureIOT. Available at: https://futureiot.tech/thailands-eec-on-track-with-digital-innovation-hub-goal/

Raymond, G., 2021. Jagged Sphere. Lowy Institute Analyses. Available at: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/jagged-sphere

S&P, 2023. Singapore economy continues to be hit by slumping exports. Available at: https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/mi/research-analysis/singapore-economy-continues-to-be-hit-by-slumping-exports-sep23.html#:~:text=Singapore’s%20economic%20growth%20momentum%20in,contracting%20manufacturing%20output%20and%20exports.

Sangfor, 2023. What Is Data Localization? A Special Focus on Southeast Asia. Available at: https://www.sangfor.com/blog/cloud-and-infrastructure/what-is-data-localization-a-special-focus-on-se-asia

Singapore Academy of Corporate Management, 2024. Demographics of Singapore. Available at: https://singapore-academy.org/index.php/en/education/library-media-center/singapore-presentation/item/218-people-and-nationalities-of-singapore

Singapore Declaration, 2024. Building an Inclusive and Trusted Digital Ecosystem. Available at: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/ENDORSED-Singapore-Declaration_30-Jan-2024-CLN.pdf

Singapore Department of Statistics, 2024a. Foreign Direct Investment in Singapore by Industry (Stock as at Year-End). Available at: https://tablebuilder.singstat.gov.sg/table/TS/M084831

Singapore Department of Statistics, 2024b. Principal Statistics of Foreign Direct Investment in Singapore. Available at: https://tablebuilder.singstat.gov.sg/table/TS/M083791

Singapore Department of Statistics, 2024c. Gross Domestic Product at Current Prices, By Industry (SSIC 2020). Available at: https://tablebuilder.singstat.gov.sg/table/TS/M015731

Singapore Department of Statistics, 2024d. Gross Domestic Product in Chained (2015) Dollars, By Industry (SSIC 2020). Available at: https://tablebuilder.singstat.gov.sg/table/TS/M015721

Singapore Department of Statistics, 2024e. Foreign Direct Investment in Singapore by Industry (Stock as at Year-End). Available at: https://tablebuilder.singstat.gov.sg/table/TS/M084831

Singapore Department of Statistics, 2024f. Return On Foreign Direct Investment in Singapore by Industry (During The Year). Available at: https://tablebuilder.singstat.gov.sg/table/TS/M084911

Singapore Department of Statistics, 2024g. Income of Foreign Direct Investment in Singapore by Industry (During The Year). Available at: https://tablebuilder.singstat.gov.sg/table/TS/M084871

Singapore Government, SG101, 2024. 1997 to 2009: Overcoming Multiple Crises. Accessed at: https://www.sg101.gov.sg/economy/growing-our-economy/1997/#:~:text=In%201997%2C%20during%20the%20Asian,global%20financial%20crisis%20in%202008

Singh, R., Naharu, M.A., 2023. Malaysia, the Next Regional Data Center Hub. The Malaysian Reserve. Available at: https://themalaysianreserve.com/2023/04/17/malaysia-the-next-regional-data-centre-hub/

Smart Nation Singapore. Transforming Singapore Through Technology. Available at: https://www.smartnation.gov.sg/about-smart-nation/transforming-singapore/

Temasek Review, 2023. A Trusted Steward. Available at: https://www.temasekreview.com.sg/stewardship/a-trusted-steward.html

Trademap, 2024. Available at: https://www.trademap.org

UNCTADStat, 2024. Merchandise: Total trade and share, annual. Available at: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/dataviewer/US.TradeMerchTotal

Vietnam Plus., 2021 Indonesia Aims for 40pct of ASEAN’s Digital Economy Market Share by 2025. Available at: https://en.vietnamplus.vn/indonesia-aims-for-40-pct-of-aseans-digital-economy-market-share-by-2025/206855.vnp

WIPO, 2023. Global Innovation Index 2023 Innovation in the face of uncertainty. Available at: https://wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo-pub-2000-2023-en-main-report-global-innovation-index-2023-16th-edition.pdf

World Bank, 2024. Individuals using the Internet (% of population) - Singapore. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=SG

Xinhua, 2022. Myanmar Inaugurates Lancang-Mekong Data Center. Available at: http://www.lmcchina.org/eng/2022-09/01/content_42098568.html

Notes

1 US dollars, unless noted otherwise.

2 Excluding holding companies.

3 See also: Wong, J., Tan, K.S., Mu, Y., Tong, S., Lim, T.S., 2009. Study on Singapore’s Experience of Regional Economic Cooperation. Research Collection School of Economics, No 6. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2177&context=soe_research

4 For more details, see: Kanaev, E.A., Liu Xintao, 2022. Asia-Pacific Security Systems: Dynamics and Factors of Development. Southeast Asia: Actual Problems of Development, Vol. 2, No 2 (55). P. 11-25.

5 See Figure 9. Brands Most Targeted by Phishing Attacks. ASEAN Cyberthreat Assessment 2021. Interpol. [n.p.] P. 16. Available at: https://www.interpol.int/content/download/16106/file/ASEAN%20Cyberthreat%20Assessment%202021%20-%20final.pdf

6 See, for example: Rozhkova, M.A., 2020. Is digital law a branch of law and should we expect the emergence of the Digital Code? Khozyaistvo i pravo (Economic and Law), No 4. P. 3-13 (in Russian).

7 See also: Panday, J., Malcolm, J., 2018. The Political Economy of Data Localization. PACO, Issue 11(2), P. 511–527. P. 515. Available at: http://siba-ese.unisalento.it/index.php/paco/article/viewFile/19553/16635

1.jpg)