Progress toward SDG 1. One Step Forward, Two Steps Back in the Poorest Countries’ Catching Up?

[Чтобы прочитать русскую версию статьи, выберите русский в языковом меню сайта.]

Dzhanneta Medzhidova is a senior advisor to the executive director at World Bank Group.

ORCID: 0000-0003-1063-3162

For citation: Medzhidova, Dzhanneta, 2023. Progress toward SDG 1. One Step Forward, Two Steps Back in the Poorest Countries’ Catching Up? Contemporary World Economy, Vol. 1, No 3.

Keywords: SDGs, global financial crisis, poverty eradication, Coronacrisis, catching-up development.

The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author. It does not purport to reflect the views or opinions of the World Bank Group or its members.

Abstract

The UN Sustainable Development Goals were adopted in 2015, and their implementation was envisioned by 2030. However, at the midway point of 2023, the successes look modest, and the unresolved challenges require enormous efforts on the part of the global community in terms of consolidation and financing. The complexity of the SDG implementation is largely due to the changes in macroeconomic conditions: the world today is far from the expectations of the global community 8 years ago. At the same time, it was during the intercrisis period (2010-2019) that the global development agenda took shape and the framework conditions for its realization were formed. This paper is devoted to a comparative study of two major crises of recent years and their consequences in the context of solving global problems using the example of SDG 1 (poverty eradication). The fight against poverty is complicated by regional specifics and new external conditions: the crisis of global governance, the growth of sovereign debt, the tightening of monetary policy in developed countries, insufficient investment, growing inequality, as well as the prioritization of other goals with the limited financial resources of the world community. All this puts the realization of SDG 1 and the 2030 Agenda at risk and at the same time creates conditions for revision of the current global development agenda.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the 21st century, we have witnessed the formation and transformation of the global development agenda: from the Millennium Development Goals adopted in 2000 to the Sustainable Development Goals adopted in 2015. The two “lists” of the most important global challenges, the solution of which will determine the well-being not only of the present but also of future generations, have been supplemented by agreements in a wide range of sectors, from financial stability and debt settlement to climate change.

The final assessment of the success in realizing the goals set by the global community is still a long way off. But we can already critically examine the period from 2008 to 2021. Two factors justify the importance of such an analysis.

First, during this period that the current global development agenda was formed and formalized, which was expected to determine the points of application of more coordinated efforts of the global community. Its main provisions were formed by 2015 and included the postcrisis financial architecture, the definition of new global objectives–the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as well as the actualization of the climate issue (Paris Agreement). Subsequently, we have seen the development and transformation of this agenda, its adaptation to new conditions, including in the context of the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Secondly, from 2008 to 2021, the global economic landscape and the framework conditions that determine and limit the possibility of achieving the set goals were also changing. Thus, macroeconomic conditions differed significantly from the favorable conditions of the first decade of the 21st century. Despite low interest rates, the growth of the global economy slowed down, the problems related to global governance and priority setting in the context of limited resources allocated to development assistance became more acute. At the same time, procrastination in addressing global challenges leads to further deterioration of the situation and increased demand for resources (primarily financial) thereafter.

To date, a considerable amount of literature on the assessment of the implementation of the 2030 Agenda has been accumulated. Critical articles assessing global development tend to involve assessing the effectiveness of achieving certain quantitative indicators (the most significant of which is economic growth) in individual countries [Diep et al. 2020], regions [Omisore 2018], or at the global level [Janouškova et al. 2018; Wu et al. 2022]. A number of studies focus on the prospects of SDG realization—for example, the work of Crespo Cuaresma et al. (2018) on the prospects of achieving SDG 1 indicators. Quite a lot of attention has been paid to quantitative estimates of the probability of successfully achieving the SDGs, including those taking into account the corona crisis [Babier, Burgess 2020]. We do not aim to identify predictive indicators of success within the framework of the 2030 Agenda or to determine the causes and consequences of the SDGs’ realization.

This study analyzes the specifics of global development in 2010-2021, its individual directions, and the factors that influenced it. The first part is devoted to a comparative study of the two major crises of recent decades—the global financial crisis and the coronavirus crisis—from the perspective of their impact on the sustainable development agenda. The second part covers the intercrisis period and critically assesses the challenges associated with the implementation of SDGs, using SDG 1 as an example. The third part of the study is the author’s attempt to assess the impact of the pandemic on progress towards global goals and outlines the most significant factors slowing it down.

1. The global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic

The period analyzed in this study (2010-2019) is limited by two major crises since the beginning of the 21st century: the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 and the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Both of these phenomena have largely determined the format or model of global development and its dynamics, as well as revealed internal problems and contradictions hindering the achievement of global goals. Given the fundamentally different nature of the two crises, it seems rational to identify some similarities and differences between them in order to determine the specificity of their impact on the responses to global challenges.

Despite the fact that there has been a significant deterioration of the situation in the subprime market already since 2005 [Pajarskas, Joiene 2014. P. 95], the crisis broke out only in 2007-2009. Following the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, which was a turning point for financial markets [Ivashina, Scharfstein 2010. P. 335], the crisis in the US mortgage market resulted in the entire global financial system crisis. Researchers attribute the reasons for its emergence to changes in regulation, weakness of regulatory oversight, and lower lending standards during a period of abnormally low interest rates [Bordo 2008].

Today, a large body of research is being conducted to analyze the global financial crisis from different perspectives. Despite the consensus on the cyclical nature of the crisis, the authors emphasize other factors underlying its occurrence on such a scale. For example, R. Shiller draws attention to behavioral peculiarities and irrationally made decisions, which significantly impact the dynamics of market development [Akerlof, Shiller 2010]. However, this “influence” itself is extremely difficult to quantify. Other researchers, such as J. Stiglitz, pay attention not only to the factors that contributed to the emergence of a crisis of this scale but also to the behavior of financial authorities to combat it, which was aimed primarily at saving large financial actors under the slogan “too big to fail” [Stiglitz 2009].

Amidst a stressful environment in November 2008, the “Group of 20” (G20) adopted a declaration1 on the causes of the financial crisis (“inconsistent and insufficiently coordinated macroeconomic policies and inadequate structural reforms that led to unstable global macroeconomic outcomes”) and on a plan for further steps to strengthen the financial system, including greater transparency and accountability, strengthening quality regulation, ensuring the coherence of financial markets, reforming international financial organizations, and others.

One of the main consequences of the financial crisis was the Basel Accords, which were designed to “fix” the global financial architecture, as well as the creation of the Financial Stability Board. Basel III implied, among other things, changes in the requirements for the basic capital and special reserves of financial organizations, as well as the levels of leverage and liquidity [Podrugina, Tabakh 2021. P. 282]. This document formed the basis of the framework approach of the world’s largest economies to overcome the consequences of the crisis and restructure the financial architecture.

A crisis, which clearly demonstrates the vulnerability of the economic system, is also an opportunity to revise the dominant paradigm. Thus, although the global financial crisis could have become a starting point for the revision of specific approaches to development in terms of industrial policy, the dangers associated with further integration, as well as macroeconomic policy and its regulation [Rogers 2010], a radical revision of positions did not occur, which was expected even after the end of the crisis [McCulloch, Sumner 2009; Makarov, Makarova 2021].

Even though already in 2010 the world GDP grew by 4.5% and surpassed the pre-crisis level, in some regions (primarily in Europe) its echo led to a prolonged recession. The latter, in turn, contributed to the creation of new and transformation of existing institutions [Gocaj, Meunier 2013]. The struggle of financial authorities with the “weaknesses” of the existing system can be called successful: many factors that created the conditions for the financial crisis (especially in the banking sector) were eliminated. However, there was no quick and effective solution to other issues important for global development (first of all, the debt problem in developing countries).

The next crisis of global scale would occur only in 10 years but would not affect the financial sector. The 2020 recession was caused by an external shock—the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to a 3.1% reduction in global GDP (World Bank estimate). The uniqueness of the crisis that occurred was manifested in three of its features: exogeneity, the uncertainty it created, as well as the global nature of the crisis and the simultaneity of countries entering the recession [Borio 2020. P. 181]. In addition, the crisis of 2020 broke out in the phase of “unfinished recovery” of the global economy [Grigoryev, Pavlyushina, Muzychenko 2020; Grigoryev 2023]. The trigger of the new recession was a global health threat. The pandemic led to simultaneous shocks on the supply and demand side: production stoppage was accompanied by a decline in consumer activity [Buklemishev 2020. P. 15-16]. Synchronicity and coverage of the introduced measures prepared the ground for the formation of bottlenecks, which will continue to hamper global development, and measures to support the population and business created prerequisites for future inflation.

To summarize, we can highlight the following key differences between the two major crises of the 21st century. First, the pandemic shock was exogenous, while the global financial crisis occurred due to an imbalance existing in the system. Second, as a consequence, the coronavirus crisis did not require introducing a set of new measures regulating the financial sector. Third, while the 2008-2009 crisis was cyclical, the new crisis came during the upswing phase, which significantly mitigated its effects. In other words, despite gloomy forecasts at the beginning of the pandemic, the liquidity squeeze did not overlap with widespread lockdowns, and the crisis hardly affected the financial sector. Fourth, the timing of the crisis recovery differed. In 2020, it was driven by the epidemiological situation both globally and in individual countries deciding to lift quarantine measures or resume tourist flows. Finally, the restrictions imposed, which slowed consumer demand, together with financial support from the government, led to an increase in savings in developed countries as well as in many upper-middle-income countries. In high-income countries (e.g., the United States), the crisis period was accompanied by an increase in demand for durable goods [Tauber, Van Zandweghe 2021], primarily in entertainment [Grigoryev et al. 2021], in others (e.g., China)—for real estate.

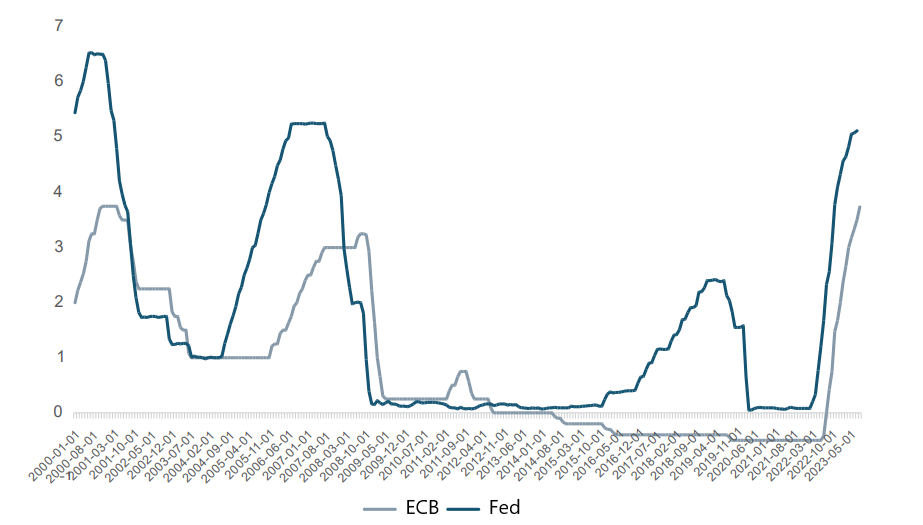

Due to the different nature of the two crises, the monetary policy aimed at mitigating their consequences was also different. In 2008–2009, there was a gradual reduction of key rates of the ECB and the Fed. The rates were also decreasing in 2020, at the beginning of the coronavirus crisis, but from 2022 onwards, they significantly increased due to the need to combat sharply increased inflation. Note that the 2020 crisis occurred against a backdrop of lower interest rates than in 2008 (see Figure 1) and a lower rate of growth in the global economy and developed economies. However, in developing countries, interest rates were far from the low levels of the US and EU, which narrowed the possibilities of fiscal stimulus [Loayza, Pennings 2020] and limited the amount of support for households and businesses.

Figure 1: ECB and Fed key rates, 2000-2023, %

Source: FRED.

2. World development between two crises

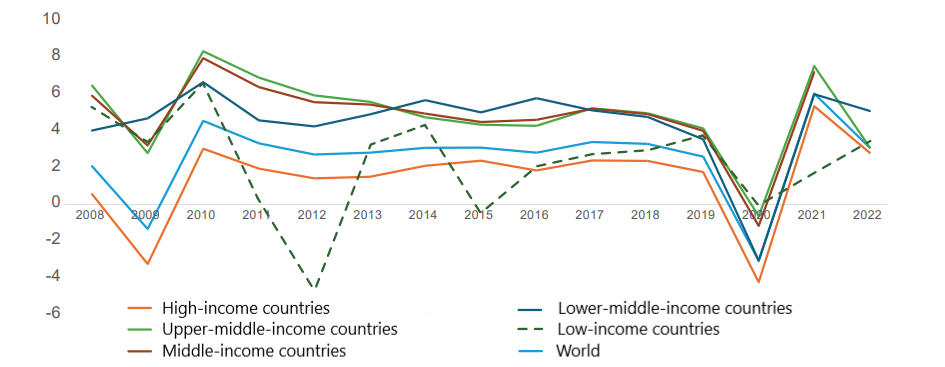

This study focuses on the global development problems between the two major crises of the 21st century. Even though these crises were of a fundamentally different nature, both in 2009 and in 2020, the high-income economies were more severely affected, with the most significant reduction in GDP (see Figure 2), due to the impact of both crises on the service sector. The GDP growth rate of the group of low-income economies in 2020 was positive (0.02%), slightly lower than that of the group of least developed economies (0.7%). Still, the economic recovery in 2021 in these groups was also less pronounced–1.78% and 1.93%, respectively.

Figure 2: GDP growth, 2008-2021, %

Source: World Bank Group.

The growth rates of the world economy in 2010-2019 were also lower than in the previous pre-crisis decade of 2000-2008 and even in 1991-2000. In addition, there was a process of slowdown in the growth rates of developed economies (primarily the United States and the EU), with high growth rates in middle-income countries (especially upper-middle-income countries). Economic growth in the first decade of the 21st century in China and India led to income growth and poverty reduction, which was of key importance for achieving individual UN Millennium Development Goals. There has also been an improvement in the situation of the poor in developing economies since the global financial crisis [Milanovic 2022]. Cabral and Castellanos-Sosa (2019) conclude in their study that the 2009 crisis led to the expected convergence and narrowing of the GDP per capita gap in Europe, as expected under the neoclassical economic model [Barro, Sala-i-Martin 1992]. However, such results do not indicate an improvement in the situation of the low-income countries but rather a deterioration in the situation of the well-to-do and richer countries. Regarding convergence between developed and developing countries, Johnson and Papageorgiou (2020) show in their paper that in recent decades, despite the high growth rates of developing countries, there has been no actual convergence between the two groups, minus a few large Asian economies.

Ötker-Robe and Podpiera (2013) identify three main channels of transmission of the financial shock: 1) the labor market (reduced employment, falling wages), 2) the financial market (reduced investment, credit squeeze), 3) private and public response strategies (reduced social payments and social spending, reduced household spending, including on health care and education). The authors also note the disproportionate impact of the crisis on the poor (job losses, educational poverty, deepening gender inequality, etc.). It should be noted that in countries where the economic situation before the crisis was difficult (slow growth, structural problems, high unemployment, high debt), the choice of anticrisis package of measures is very limited. The global financial crisis has set humanity back in terms of realizing the global goals of overcoming hunger, reducing poverty, solving health problems, etc. However, the results of MDG realization were quite positive.

However, the impact of the crisis on individual least developed countries (LDCs) was somewhat milder than initially expected due to the (financial) nature of the crisis itself and their lower integration into the global economy [Audiguier 2012]. Pre-crisis economic growth, which improved the overall situation in the countries, was also an important factor. Finally, the volume of development assistance was not reduced, providing the necessary resources for anticrisis measures. The most serious challenge, however, was the reduction in global demand.

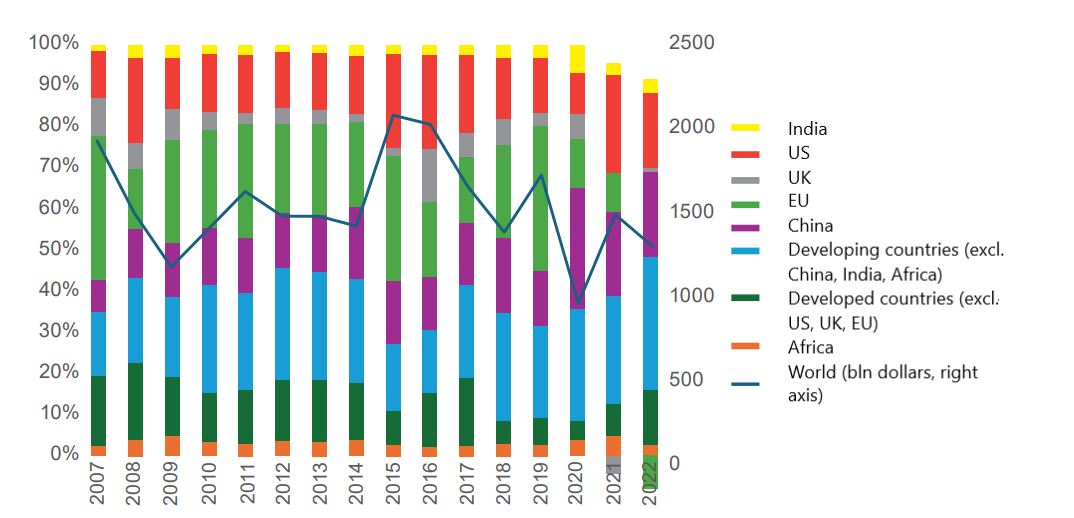

In the context of global development, it is difficult to overestimate the importance of crisis events, especially if they are structural, as it happened in 2008, or deep crises (record GDP decline in 2020). A decline in global GDP usually leads to a decline in foreign direct investment (FDI) [Dornean and Oanea 2015], which in turn affects the pace of economic development of countries. The crisis can also act as a trigger for the transformation of investment flows [Stoddard, Noy 2015]. In 2008-2009, according to UNCTAD, the volume of FDI in the world decreased by 38% in aggregate, and it surpassed pre-crisis levels only in 2015. In developed countries, FDI inflows in the postcrisis decade never recovered to 2007 levels, while in developing countries, this threshold was already crossed in 2010. The impact of the coronavirus crisis was also more pronounced for developed countries, where the indicator fell by 68% in 2020 (almost 9% in developing countries). Nevertheless, FDI is unevenly distributed, with the United States accounting for more than 26% of global FDI in 2021 and African countries only 5.4% (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Structure of foreign direct investment inflow, %

Source: compiled by the author on the basis of UNCTAD data.

Current estimates suggest that developing countries need an increase in financing of $4 trillion annually to achieve the SDGs [UNCTAD 2023b], more than three times the global FDI stock in 2022. The intercrisis period, as we have already noted, was characterized by low interest rates in developed countries, while the post-pandemic recovery is associated with a tightening of monetary policy by central banks in developed countries, which does not facilitate the redirection of financial flows from developed to developing countries [Bitzenis, Vlachos 2016]. Thus, recessions exacerbate existing economic problems, contributing to both the reduction of investment in developing countries and limited access to financial markets for this group of countries due to deteriorating credit ratings, increased debt, and rising borrowing costs in the context of high demand for concessional financing.

3. The new stage of world development: The 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement

The revision of the global development agenda was not a direct consequence of the financial crisis but rather the result of individual events that determined the key approaches to solving global problems.

The UN came to define the problems, the solution of which requires the efforts of all mankind at the beginning of the 21st century with the emergence of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The world community established eight global goals and defined a 15-year period until 2015 for their realization. Since then, the goals, indicators, and agenda of the MDGs have been repeatedly criticized for various reasons: due to the narrowness of the approach to poverty assessment (only absolute poverty is taken into account) and neglect of the problem of inequality (both within and between countries), overly broad coverage, vague wording and underestimated target indicators with regard to some issues [Saith 2006; Bhagwati 2010; Amin 2006; Oya 2011; Fukuda-Parr 2010; Fukuda-Parr et al. 2013]. Nevertheless, the articulation of key world problems, the development of indicators reflecting progress in their solution, and the formation of the world development agenda as a whole can be assessed positively in the context of recognizing the importance of consolidating efforts for their further solution.

The intercrisis period saw several major events, the most significant of which, in the context of this paper, are the emergence of the UN General Assembly document “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” and the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015. The first document delineated the world development agenda for the next 15 years, emphasizing 17 global challenges that need to be tackled for the well-being of humankind. The second document focused on the single issue of global climate change, defining as a goal the containment of rising temperature within 2OC with due efforts to contain temperature within 1.5OC [United Nations 2015].

The climate agenda has become a priority for developed countries and the foundation for the fourth energy transition [Makarov, Stepanov 2018], largely overshadowing other global issues. We can identify the following factors accompanying the actualization of the climate agenda: 1) the reduction in financing of projects in the field of fossil fuel extraction, which was observed until 2021, 2) the active development of projects related to renewable energy sources, primarily solar and wind power generation, 3) the introduction of commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (primarily carbon dioxide) in the development strategies of countries, 4) the emergence of new financial instruments related to climate finance (including debt), 5) the development of carbon markets and the introduction of a carbon price in many countries, as well as the emergence of frontier carbon regulation—first in the EU.

The results were mixed. As the crisis in the EU gas market has shown, weather anomalies can have a significant impact on renewable electricity generation. In the absence of cheap and capacitous energy storage capacity, fossil fuels remain essential for baseload supply [Leonard et al. 2020], and a complete phaseout at the global level and even at the level of developed countries without further technological innovations is not yet possible. The positive consequences include not only the active restructuring of the electricity generation mix in developed countries and China, the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in the EU (compared to 1990 or 2005 levels), and the development of the electric vehicle market but also the slow movement towards helping developing countries. For example, the Partnership for a Just Energy Transition in 2021 pledged $8.5 billion in financial support to South Africa to overcome its dependence on fossil fuels (primarily coal).2 In 2022, the Partnership announced support to Vietnam and Indonesia in the sums of $15.5 billion and $20 billion, respectively. The 27th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change decided to establish a Loss and Damage Fund to compensate developing countries for damage caused by natural disasters. By the beginning of 2024, the Fund amounted to US$700 million.3 However, it will take time to assess the effectiveness and feasibility of the proposed measures. It is worth mentioning that in 2009, political commitments for climate finance by 2020 (later moved to 2025) amounted to $100 billion annually [UNCTAD 2023c].

Despite the attention of the world community, especially in the EU, to the climate agenda, the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change emphasizes that humanity is still far from realizing the goal of curbing temperatures by even 2O C: all other things being equal, the temperature increase by 2100 could be more than 2.5OC [IPCC 2023]. Between 2016 and 2030, the difference between the commitments made by businesses and governments and the investments needed to achieve zero emissions by mid-century will exceed $1.6 trillion annually [IEA 2021]. If current emissions levels continue, this disparity will only widen as we approach the tipping points of temperature rise. Finally, there is an imbalance in the investments in mitigation and adaptation. Further combating climate change will require a significant increase in not only public but also private investment, technology development (hydrogen energy, carbon capture and storage, etc.), and changes in consumer behavioral habits.

This article is not intended to assess humanity’s achievements in the fight against climate change, but we can already talk about the implications of the climate agenda for global development. First, the prioritization of the climate change problem, the nature of which is genuinely global since changes affect a wide range of countries, comes into conflict with traditional development problems: fighting poverty, eradicating inequality, eliminating hunger, etc., characteristic of developing countries [Grigoryev, Medzhidova 2020]. The existence of preferences belonging to creditor (or donor) countries makes its own adjustments in allocating limited financial resources. Second, since mitigation is closely related to the introduction of renewable energy sources, this issue becomes part of trade and industrial policy and intensifies competition between countries.4 Third, taking action to combat climate change requires a high level of coordination at both the country level and the level of international institutions and global funds, which will help avoid duplication of work and allow for synergies. Finally, the lack of financing for adaptation policies and the resulting lack of infrastructure in climate-vulnerable countries in the face of increasing natural disasters can only exacerbate development challenges. In 2019/2020, “climate” finance amounted to $632 billion, but only 10% was allocated to adaptation,5 while the funding need is $160-340 billion annually until 2030 and $315-565 billion annually between 2030 and 2050 [UNEP 2022].

4. Sustainable Development Goals: The challenge of implementation using SDG 1 as an example

Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals, solution of the problems of hunger, poverty, lack of access to water and energy, maternal and child mortality, inequality, etc. is difficult to imagine without high rates of economic growth in lower-middle and low-income countries.

Differences between countries are more pronounced when analyzing individual indicators. In the context of the Sustainable Development Goals, low-income countries (26 countries) are of greatest research interest. For example, SDG 1, poverty eradication, includes several targets, including reducing the proportion of people living in poverty in all its manifestations by “at least half.”6 Statistics confirm the significant progress against poverty that humanity has made in the 21st century: the number of people living in absolute poverty (less than $2.15/day PPP 2017) has been reduced from 1.8 billion (29.3% of the world population) in 2000 to 697 million (9%).

In 2017, the share of the population living in absolute poverty globally was 10.8%, and in 2020, this number is estimated to increase by 11% to 719 million people [World Bank 2022]. At the same time, the group of low-income countries, despite the high level of average annual GDP growth in 2010-2019, the growth of GDP per capita in this period was negative (see Table 1)–due to the fact that the population growth during this period was almost twice as high as the world average.

Table 1. Development indicators by income groups, 2010-2019

|

|

Gross income per capita, USD |

Average annual GDP growth, % |

Average annual growth of GDP per capita, % |

Population, million people, 2019 |

Average annual population growth, % |

Share of the population with income below $2.15/day, 2019, % |

Share of the population with income below $3.65/day, 2019, % |

Share of the population with income below $6.85/day, 2019, % |

|

World |

- |

3.0 |

1.8 |

7743 |

1.2 |

8.5 |

24.1 |

46.9 |

|

High-income countries |

>13205 |

2.0 |

1.4 |

1237 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

1.7 |

|

Upper-middle-income countries |

4256-13205 |

5.1 |

4.3 |

2753 |

0.8 |

1.8 |

7 |

26.6 |

|

Lower-middle-income countries |

1086-4255 |

1.6 |

3.3 |

3075 |

1.5 |

11.1 |

39.9 |

77.3 |

|

Low-income countries |

<1085 |

4.8 |

-1.1 |

649 |

2.7 |

45 |

72.1 |

92.2 |

Source: compiled by the author according to the World Bank Group.

The picture of poverty alleviation, apparently successful at the global level, has its own specifics in the context of the income groups of countries. Thus, despite the significant reduction of poverty in the world as a whole, in the group of low-income countries, its average annual growth in 2011-20187 amounted to 2.3%. A higher increase in the designated period (2011-2019) was observed only in high-income countries (2.6%), and the total number of people living in absolute poverty in the world amounted to 7.4 million. The most significant decline was in upper-middle-income countries (average annual rate exceeded 17%), primarily in China. It should be noted that between 1990 and 2015. China made the largest contribution to poverty reduction, which amounted to 63.9%, and in 1990-2005 its contribution exceeded 93% [Wan, Hu, Liu 2021]. Thus, the realization of the poverty-related MDGs would not have been achievable without China’s contribution [Darvas 2019], but in the context of achieving SDG 1, its contribution is limited to the progress made earlier.

More than half of the population living on less than $2.15 a day lives in sub-Saharan Africa (see Figure 4). In the intercrisis period, the number of poor people here has remained stable and even increased. Another important region in this context is South Asia, where the number of poor people in 2021 amounted to almost 208 million, of which more than 167 million lived in India. India’s economic growth rate and current projections suggest a China-like scenario with a sharp decline in the number of poor people. However, it remains to be seen whether progress in India will enable the achievement of SDG 1 globally or whether significant intensification of poverty reduction will be required in other parts of the world, particularly in Africa.

Figure 4: Population living in absolute poverty (PPP 2017)

Source: compiled by the author based on the World Bank data.

The situation in Sub-Saharan Africa is more complex for several reasons. As the region is critical not only for poverty eradication but also for other SDGs, we will elaborate on this issue. Africa suffers from a chronic lack of investment: in 2022, foreign direct investment globally was $1.3 trillion, but in Sub-Saharan Africa it was only $30 billion. Morrissey (2012) notes that even the investments that do come into the region do not create significant preconditions for economic growth, both for domestic reasons (low levels of human capital, underdeveloped financial markets, low investment productivity, weak institutions, high levels of corruption) and because of the nature of the investments: they do not have positive externalities because they are not aimed at building an industrial base in the region.

In addition, public debt in the region has increased from 30% of GDP in 2013 to 60% of GDP by the end of 2022.8 Debt service costs are rising, reducing the ability of countries to borrow in external markets to invest in development and increasing dependence on development assistance from international development banks and on a bilateral basis. At the same time, investment needs continue to grow. Financing is needed for infrastructure construction (transport corridors), industrialization, development of local industries, support for health and education systems, climate change adaptation, and agricultural development and expansion, among other things. Poverty alleviation (as well as increasing investment attractiveness) is also directly related to institutions, the formation of which is a long process that requires the support of regional elites and local populations. Finally, the countries of the region are characterized by high levels of multidimensional poverty, i.e., absolute poverty combined with a lack of access to water supply and sanitation, health, and education services. For example, in Burundi, the share of the population in multidimensional poverty is 85.2%; in South Sudan, 84.9%; in Madagascar, 82.9%; in Niger, 80%.9

The global fight against poverty is further complicated by the fact that, according to the World Bank estimates, by 2030, 59% of the population living in absolute poverty will be in post-conflict and fragile countries.10 Diwakar (2023) identifies the following factors that exacerbate the well-being of populations in such contexts: shocks, displacement (within or across countries), instability (in the context of the performance of state institutions), security, and decentralization of power. Such a context poses additional challenges for poverty eradication. In addition, it requires investments in building institutions, preventing conflict escalation, and building peaceful lives, which in the medium term until 2030 is a complex and difficult task even without taking into account external factors that may have an even more negative impact on this group of countries.

To summarize, the implementation of SDG 1 is regionally specific, making it difficult to achieve due to both the challenges inherent to the region and the global economic situation, which directly impacts the regional situation as it is vulnerable to macroeconomic shocks. The achievement of a similar MDG target was once largely driven by the success of China, and India can make a significant contribution in the current context, but a lack of progress or deterioration in sub-Saharan Africa could put SDG 1 at risk.

5. 2021: A convulsive new recovery?

In 2021, global GDP growth amounted to 6%, and its volume exceeded the pre-crisis level. However, the recovery was uneven, with the production of goods far outpacing the production of services, partly constrained by the still-existing restrictions on flights and recreation [Grigoryev et al. 2021].

In recent years, the world economy has faced both a global crisis caused by a pandemic and crises in individual commodity markets. In 2018, the UN estimated that achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 required an annual investment of $3.3-4.5 trillion, but for 2023, it has increased significantly and ranges between $5.4-6.4 trillion.11 The challenges facing the global community are intensifying. Climate change is causing an increase in natural disasters, including floods and droughts, which undermine food security in the most vulnerable regions of the planet. The UN estimates that the number of people facing hunger will average 735 million in 2021-2022, 122 million more than in pre-crisis 2019 [FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO 2023]. The number of people without access to electricity (living predominantly in low-income countries) was 675 million in 2021, to clean and safe fuels and cooking technologies—2.3 billion [IEA, IRENA, UNSD, World Bank, WHO 2023]. As recently as 2019, the educational poverty rate in developing countries was 57% and is estimated to rise to 70% in 2022,12 leading to a 10% drop in income for this generation. Halfway to achieving the SDGs, only 15% are on track and 37% are making no progress or have regressed [United Nations 2023]. Such a picture signals the need for rapid consolidation of the global community to achieve global development goals, without which their successful implementation cannot be expected [Yuan et al. 2023].

In the context of post-pandemic global challenges and the threat of non-compliance with the UN SDGs, there has been an increase in “world” total public debt, which in 2022 amounted to US$92 trillion. Developing countries account for only 30% of the total, of which China, India and Brazil account for about 70%. However, low-income countries have higher public debt-to-GDP ratios, which has increased the number of countries in debt distress from 22 in 2011 to 59 in 2022 [UNCTAD 2023a]. After the global financial crisis, public debt has been growing steadily against the background of low interest rates, and the most significant increase was observed during the coronavirus crisis due to fiscal and monetary measures taken by the authorities to support the population and businesses [Makin, Layton 2021]. Thus, in 2020, the global public and private debt growth amounted to 28%. The “debt landscape” is also changing: the number of creditors is increasing (including non-Paris Club creditors), the volume of non-concessional debt lending is increasing, as well as the volume of domestic debt; new debt instruments are used [Chuku et al. 2023]. The G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments is constantly criticized,13 because achieving debt settlement through this channel is a protracted process, and only one country managed to achieve the result. The Paris Summit on transforming the global financial architecture, held in June 2023, also failed to produce any meaningful results, except for the announcement of debt restructuring for Zambia, which defaulted in 2020. Thus, it is difficult to conclude about the effectiveness of the existing system in case the debt crisis affects many middle-income countries [Essers, Cassimon 2021]. For example, in August 2023, the IMF approved a tranche of $7.5 billion for Argentina,14 whose outstanding loans to the organization amount to more than $31 billion, or 28.2% of total outstanding loans.15

As we have already noted, the coronavirus crisis has played an important role in exacerbating global challenges and has had a negative impact on the prospects for the realization of all SDGs. Cheng et al. (2021. P. 15-17), in their analysis of the consequences of the pandemic, draw attention to the disproportionate negative impact on the most vulnerable segments of the population (individual countries and the group of least developed countries) in terms of increasing the number of poor people, aggravating the problem of food security, health, education, gender inequality, and others. The authors propose some measures that can help achieve the SDGs: combine individual goals and maximize synergies between individual SDGs, set short- and long-term priorities, strengthen global cooperation, assess and forecast the process of achieving the SDGs in a timely manner, and so on. Despite heterogeneous progress (and regression) at the global level, it can be noted that the Sustainable Development Goals are unlikely to be achieved in their current form.

At the same time, the global community could benefit from the current situation: revising the SDGs from the perspective of the value of human capital [Bobylev, Grigoriev 2020], forming a single clear consolidating agenda with the prioritization of individual SDGs, or forming new unifying SDGs. Regardless of the details of the “rethinking” SDGs, to which a body of work by foreign and domestic researchers is devoted, the global SDG agenda should not only change the discourse of global development by shifting the emphasis but also serve as a realistic goal achievable in the foreseeable future, rather than a speculative construct of the most desirable future.

The actual agenda for 2023 is radically different from the 2015 picture of the future: economic growth has slowed down, coordination and partnership have been replaced by geo-fragmentation, sovereign debt of developing countries is growing, depriving them of access to financial resources for independent solutions of domestic issues. Even the issue of climate change, despite the enormous attention of politicians, nonprofit organizations, international institutions, and civil society, remains as acute as ever. Finally, the impact of the pandemic has yet to be assessed, but it is already clear that COVID-19 has set back the implementation of the SDGs by years, if not decades. A recent IMF report shows a new trend: the medium-term slowdown in developing economies is slowing convergence between developed and developing countries [IMF 2023], something that is no closer to resolving global problems, the consequences of which affect middle- and low-income countries to a greater extent.

Conclusions

The crises of the last 15 years have had a significant impact on global development. The global financial crisis has largely determined the paradigm of global development for the next decade, including the formation of the UN’s Agenda 2030 and the development of the climate agenda. The intercrisis period 2010-2019, which is the focus of this paper, has a number of distinctive characteristics, including low growth rates (relative to previous periods), low interest rates, rising public debt in developing countries, slow progress or even regression in the realization of global goals (e.g., rising poverty in sub-Saharan Africa). In addition, there is increasing “competition” between different development goals in resource-limited settings, in particular between the goal of combating climate change and other goals related to economic growth and development in low-income countries. Post-crisis recovery has been slowed by high inflation, rising interest rates, and high commodity prices (especially food and fuel). Each year of slow progress or even regression in achieving the SDGs means the need to intensify global efforts in the remaining period, which, in turn, is impossible without a significant increase in financing.

Halfway to the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal target date, progress remains modest: the gains made on many fronts (poverty, hunger, education poverty, etc.) have been reversed by the pandemic, and the likelihood of achieving them within the target date is, all other things being equal, extremely low. The midway point is an important point, a good time to reflect not only on the obstacles to realizing the SDGs but also on their very nature. A reassessment of current priorities is also required: quantitative indicators related to economic growth should not be more important than improving the quality of life and human capital development, and the prioritization of quantitative indicators related to economic growth over human capital development and improving the quality of life should be reconsidered.

Bibliography

Akerlof, G. A., Shiller, R. J., 2010. Animal spirit: How human psychology drives the economy, and why it matters for global capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Amin, S., 2006. The millennium development goals - A critique from the South. Monthly Review – an Independent Socialist Magazine. 57(10). Available at: https://monthlyreview.org/2006/03/01/the-millennium-development-goals-a-critique-from-the-south/

Audiguier, C., 2012. The impact of the global financial crisis on the Least Developed Countries. FERDI Working Paper No 50. FERDI.

Babier, E. B., Burgess, J. C., 2020. Sustainability and development after COVID-19. World Development. 135. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105082

Barro, R. J., Sala-i-Martin, X., 1992. Convergence. Journal of Political Economy. 100 (2). P. 223-251.

Bhagwati, J., 2010. Time for a Rethink. Finance & Development. 47 (3). Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2010/09/pdf/25hagwati.pdf

Bitzenis, A., Vlachos, V., 2016. Editorial: Foreign direct investment in the light of the recent crisis. Global Business and Economics Review. 18 (2). P. 115-123.

Bobylev S., Grigoryev L., 2020. In search of the contours of the post-COVID Sustainable Development Goals: The case of BRICS. BRICS Journal of Economics. 2(1). P. 4–24. Available at: https://doi.org/10.38050/2712-7508-2020-7

Bordo, M. D., 2008. An historical perspective on the crisis of 2007-2008. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper 14569. Available at: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w14569/w14569.pdf

Borio, C., 2020. The Covid-19 economic crisis: dangerously unique. Business Economics. 55. P. 181-190. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/s11369-020-00184-2

Buklemishev, O., 2020. Coronavirus crisis and its effects on the economy. Population and Economics. 4 (2). P. 13-17. Accessed: https://doi.org/10.3897/popecon.4.e53295

Cabral, R., Castellanos-Sosa, F. A., 2019. Europe’s income convergence and the latest global financial crisis. Research in Economics. 73 (1). P. 23-34. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rie.2019.01.003

Cheng, Y., Liu, H., Wang, S., Cui, X., Li, Q, 2021. Global Action on SDGs: Policy Review and Outlook in a Post-Pandemic Era. Sustainability. 2021. 13. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116461

Chuku, C., Samal, P., Saito, J., Hakura, D., Chamon, M., Cerisola, M., Chabert, G., Zettelmeyer, J., 2023. Are We Heading for Another Debt Crisis in Low-Income Countries? Debt Vulnerabilities: Today vs. the pre-HIPC Era. IMF WP/23/79. IMF.

Crespo Cuaresma, J., Fengler, W., Kharas, H. et al., 2018. Will the Sustainable Development Goals be realized? Assessing present and future global poverty. Palgrave Communications. 4. P. 29. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0083-y

Darvas, Z., 2019. Global interpersonal income inequality decline: The role of China and India. World Development. 121. P. 16-32. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.04.011

Diep, L., Martins, F. P., Campos, L. C., Hofmann, P., Tomei, J., Lakhanpaul, M., Parikh, P., 2020. Linkages between sanitation and the sustainable development goals: A case study of Brazil. Sustainable Development. 29 (2). P. 339-352. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2149

Diwakar, V., 2023. Ending extreme poverty amidst fragility, conflict, and violence. DEEP Thematic Paper 2. Data and Evidence to End Extreme Poverty Research Program. Oxford. Available at: https://doi.org/10.55158/DEEPTP2

Dornean, A., Oanea, D.-C., 2015. Impact of the Economic Crisis on FDI in Central and Eastern Europe. Review of Economic and Business Studies. 8 (2). P. 53-68.

Essers, D., Cassimon, D., 2022. Towards HIPC 2.0? Lessons from past debt relief initiatives for addressing current debt problems. Journal of Globalization and Development. 13 (2). P. 187-231. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/jgd-2021-0051

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, 2023. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Urbanization, agrifood systems transformation and healthy diets across the rural-urban continuum. Rome: FAO. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4060/cc3017en

Fukuda-Parr, S., 2010. Reducing inequality — The missing MDG: A content review of PRSPs and bilateral donor policy statements. IDS Bulletin-Institute of Development Studies. 41 (1). P. 26-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00100.x

Fukuda-Parr, S., Greenstein, J., Stewart, D., 2013. How should MDG success and failure be judged: Faster progress or achieving the targets? World Development. 41. P. 19-30. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.06.014

Gocaj, L., Meunier, S., 2013. Time Will Tell: The EFSF, the ESM, and the Euro Crisis. Journal of European Integration. 35 (3). P. 239-253. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2013.774778

Grigoryev, L. M., 2023. The Shocks of 2020-2023 and the Business Cycle. Contemporary World Economy. No 1 (1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.17323/2949-5776-2023-1-1-8-32

Grigoryev, L. M., Pavlyushina, V. A., Muzychenko, E. E., 2020. Fall into the global recession 2020. Voprosy ekonomiki. 2020. 5. P. 5-24. Available at: https://doi.org/10.32609/0042-8736-2020-5-5-24 (in Russian).

Grigoryev, L. M., Yolkina, Z. S., Mednikova, P. A., Serova, D. A., Starodubtseva, M. F., Filippova, E. S., 2021. “Perfect storm” of personal consumption. Voprosy ekonomiki. 2021. 10. Available at: https://doi.org/10.32609/0042-8736-2021-10-27-50 (in Russian).

Grigoryev, L. M., Medzhidova, D. D., 2020. Global energy trilemma. Russian Journal of Economics. 6 (4). P. 437-462. Available at: https://doi.org/10.32609/j.ruje.6.58683

IEA, 2021. World Energy Outlook 2021. Accessed: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2021

IEA, IRENA, UNSD, World Bank, WHO, 2023. Tracking SDG 7: The Energy Progress Report. Washington, DC: World Bank.

IMF, 2023. Navigating global divergences. 2023. Accessed: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2023/10/10/world-economic-outlook-october-2023

IPCC, 2023. AR6 Synthesis Report. Climate Change 2023. Accessed: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/

Ivashina, V., Scharfstein, D., 2010. Bank lending during the financial crisis of 2008. Journal of Financial Economics. 97(3). P. 319-338. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2009.12.001

Janoušková, S., Hák, T., Moldan, B., 2018. Global SDGs Assessments: Helping or Confusing Indicators? Sustainability. 10(5). P. 1540. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051540

Johnson, P., Papageorgiou, C., 2020. What Remains of Cross-Country Convergence? Journal of Economic Literature. 58(1). P. 129-175. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20181207

Leonard, M. D., Michaelides, E. E., Michaelides, D. N., 2020. Energy storage needs for the substitution of fossil fuel power plants with renewables. Renewable Energy. 145. P. 951-962. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.06.066

Loayza, N., Pennings, S. M., 2020. Macroeconomic Policy in the Time of COVID-19: A Primer for Developing Countries. World Bank Research and Policy Briefs No. 147291. World Bank. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3586636

Makarov, I. A., Makarova, E. A., 2021. Ringing the bell without consequences. Learned and unlearned lessons of the Great Recession. Russia in Global Affairs. 2021. No 1. Available at: https://doi.org/10.31278/1810-6439-2021-19-1-62-79 (in Russian).

Makarov, I. A., Stepanov, I. A., 2018. Paris agreement on climate change: Its impact on world energy sector and new challenges for Russia. Current Problems of Europe. 1. P. 77-100 (in Russian).

Makin, A. J., Layton, A., 2021. The global fiscal response to COVID-19: Risks and repercussions. Economic Analysis and Policy. 69. P. 340-349. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2020.12.016

McCulloch, N., Sumner, A., 2009. Will the Global Financial Crisis Change the Development Paradigm? IDS Bulletin. 40. P. 101-108. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2009.00078.x

Milanovic, B., 2022. After the Financial Crisis: The Evolution of the Global Income Distribution between 2008 and 2013. Review of Income and Wealth. 68 (1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12516

Morrissey, O., 2012. FDI in Sub-Saharan Africa: Few Linkages, Fewer Spillovers. The European Journal of Development Research. 24. P. 26-31. Accessed: https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2011.49

Omisore, A. G., 2018. Attaining Sustainable Development Goals in sub-Saharan Africa; The need to address environmental challenges. Environmental Development. 25. P. 138-145. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2017.09.002

Ötker-Robe, İ., Podpiera, A., 2013. The Social Impact of Financial Crises: Evidence from the Global Financial Crisis. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6703. World Bank.

Oya, C., 2011. Africa and the millennium development goals (MDGs): What’s right, what's wrong and what’s missing. Revista De Economia Mundial. 27. P. 19-33.

Pajarskas, V., Jočienė, A., 2014. Subprime Mortgage Crisis in the United States in 2007-2008: Causes and Consequences (Part I). Ekonomika. 93 (4). P. 85-118.

Podrugina, A., Tabakh, A., 2022. Financial regulation in the XXI century. In: World economy in the period of great shocks. Moscow: INFRA-M. Chap. 11. P. 274-294 (in Russian).

Rogers, F. H., 2010. The Global Financial Crisis and Development Thinking. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5353. World Bank.

Saith, A., 2006. From Universal Values to Millennium Development Goals: Lost in Translation. Development and Change. 37 (6). P. 1167-1199. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2006.00518.x

Stiglitz, J. E., 2009. The Financial Crisis of 2007/2008 and its Macroeconomic Consequences. Initiative for Policy Dialogue Working Paper Series. Initiative for Policy Dialogue. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7916/D8 Q Z2HSG

Stoddard, O., Noy, I., 2015. Fire-sale FDI? The Impact of Financial Crises on Foreign Direct Investment. Review of Development Economics. 19 (2). P. 387-99. Available at: https://doi.org/DOI:10.1111/rode.12149

Tauber, K., Van Zandweghe, W., 2021. Why Has Durable Goods Spending Been So Strong during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Economic Commentary. 2021. Available at: https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-202116

UNCTAD, 2023a. A world of debt. A growing burden to global prosperity. Accessed at: https://unctad.org/publication/world-of-debt

UNCTAD, 2023b. World Investment Report. United Nations.

UNCTAD, 2023c. Considerations for a New Collective Quantified Goal Bringing accountability, trust and developing country needs to climate finance. Available at: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/gds2023d7_en.pdf

UNEP, 2022. Adaptation Gap Report 2022. Available at: https://www.unep.org/resources/adaptation-gap-report-2022

United Nations, 2015. Paris Agreement. Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf

United Nations, 2023. The Sustainable Development Goals Report. Special Edition. Available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20report%2C%20the,hindered%2 0 progress%20towards%20the%20Goals

Wan, G., Hu, X., Liu, W., 2021. China’s poverty reduction miracle and relative poverty: Focusing on the roles of growth and inequality. China Economic Review. 68. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101643

World Bank, 2022. Poverty and shared prosperity 2022. Correcting Course. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/b96b361a-a806-5567-8e8a-b14392e11fa0/content, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1893-6 .

Wu, X., Fu, B., Wang, S. et al., 2022. Decoupling of SDGs followed by re-coupling as sustainable development progresses. Nature Sustainability. 5. P. 452-459. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00868-x

Yuan, H., Wang, X., Gao, L. et al., 2023. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals has been slowed by indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Communications Earth & Environment. 2023. 4. 184. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00846-x

Notes

1 Declaration of the Summit on Financial Markets and the World Economy. November 15, 2008. Available at: http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2008/2008declaration1115.html

2 Kramer, K., 2022. Just Energy Transition Partnerships: An opportunity to leapfrog from coal to clean energy. IISD. Dec. 7. Available at: https://www.iisd.org/articles/insight/just-energy-transition-partnerships

3 Lakhani, N., 2023. $700m pledged to loss and damage fund at Cop28 covers less than 0.2% needed. The Guardian. Dec. 6. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/dec/06/700m-pledged-to-loss-and-damage-fund-cop28-covers-less-than-02-percent-needed

4 Martina M. et al., 2021. U.S. bans imports of solar panel material from Chinese company. Reuters. Jun. 24. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/us-restricts-exports-5-chinese-firms-over-rights-violations-2021-06-23/

5 Buchner B. et al., 2021. Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2021. CPI. Dec. 14. Available at:

https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-2021/

6 Goal 1: Eradicate poverty in all its forms everywhere. Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ru/poverty/

7 Data for 2019 are not yet available.

8 Comelli, F. et al., 2023. How to Avoid a Debt Crisis in Sub-Saharan Africa. IMF. Sept. 26. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/09/26/cf-how-to-avoid-a-debt-crisis-in-sub-saharan-africa

9 World Bank data.

10 Fragility, Conflict & Violence. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fragilityconflictviolence/overview

11 Annual cost for reaching the SDGs? More than $5 trillion. United Nations. Sep. 19, 2023. Available at:

12 Learning in Crisis: Prioritizing education & effective policies to recover lost learning. World Bank. August 19, 2022. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/immersive-story/2022/09/16/learning-in-crisis-prioritizing-education-effective-policies-to-recover-lost-learning#:~:text=These%20learning%20losses%20are%20are%20expected,have%20also%20been%20greatly%20affected.&text=The%20new%20estimate%20shows%20that,are%20now%20out%20of%20reach

13 Georgieva, K., Pazarbasiogli, C., 2021.The G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments Must Be Stepped Up. // IMF. Dec. 2. Available at: https://meetings.imf.org/en/IMF/Home/Blogs/Articles/2021/12/02/blog120221the-g20-common-framework-for-debt-treatments-must-be-stepped-up

14 IMF Executive Board Completes the Combined Fifth and Sixth Reviews of the Extended Arrangement Under the Extended Fund Facility for Argentina. IMF. Aug. 23, 2023. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/08/23/pr23290-argentina-imf-executive-board-completes-combined-fifth-sixth-rev-extended-arr-under-eff

15 Total IMF Credit Outstanding. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/tad/balmov2.aspx?type=TOTAL

1.jpg)